Here's a bonus New Year’s issue for you all. I'll try and keep it short and to the point.

While I've put writing about economics on the back burner for now, there are a few very simple principles that are so basic to understanding the subject that I think everyone would benefit from incorporating them into their cognitive toolkit. I think they will be useful as you read about the economy over the coming year.

Despite the simplicity and importance of these principles, I rarely see them explicitly spelled out for some reason. So I'm going to try to do that. I'm going to keep this simple for now, but each principle could be an entire newsletter on its own.

There's something that I call the Duality Principle. There's probably a better term for it, but I haven't come up with one yet. To my mind, it's the most important insight I've gained in trying to wrap my head around economics and finance matters.

Economics courses usually start by describing binary transactions between buyers and sellers in imaginary, perfectly idealized markets.

In markets, for every buyer, there is also a seller, that's true. But also:

For every asset, there must be a corresponding liability.

For every debtor, there must also be a creditor.

For every deficit there is a corresponding surplus.

For every seller there must be a buyer.

One person's spending is another person's income.

These things are always true. One cannot exist without the other, just as a one-sided coin cannot exist. When one arises, so, too, does it's compliment.

This is due to the nature of double-entry bookkeeping, which capitalism runs on. You could make the case that capitalism began with the adoption of double-entry bookkeeping in Europe during the Middle Ages—first in Venice, then in other Italian city-states, then in Western Europe more generally.

As an aside, I find it interesting that accounting, like business and marketing, is taught in a completely different school than economics in universities, often in another part of the campus with no overlap between classes. That should give you an indication of how relevant studying economics is to understanding how our economy actually—as opposed to theoretically—works.

The reason why these facts are so important is that, if you're only looking at one side of the equation, then you can’t really understand how the economy works.

If you take nothing away from this essay, or my writing about economics in general, let it be this: if someone is only talking about one of these things without talking about the other, you should stop listening to them. Their analysis is bogus, and they are probably trying to mislead or bamboozle you, or pull the wool over your eyes in some way.

Let's take some examples of how the above principles might change your thinking about certain topics.

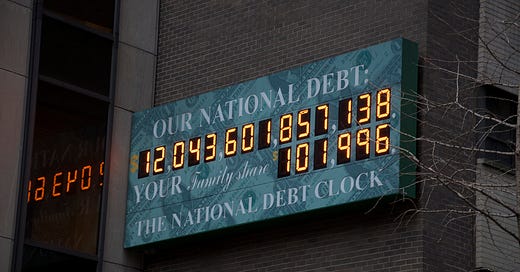

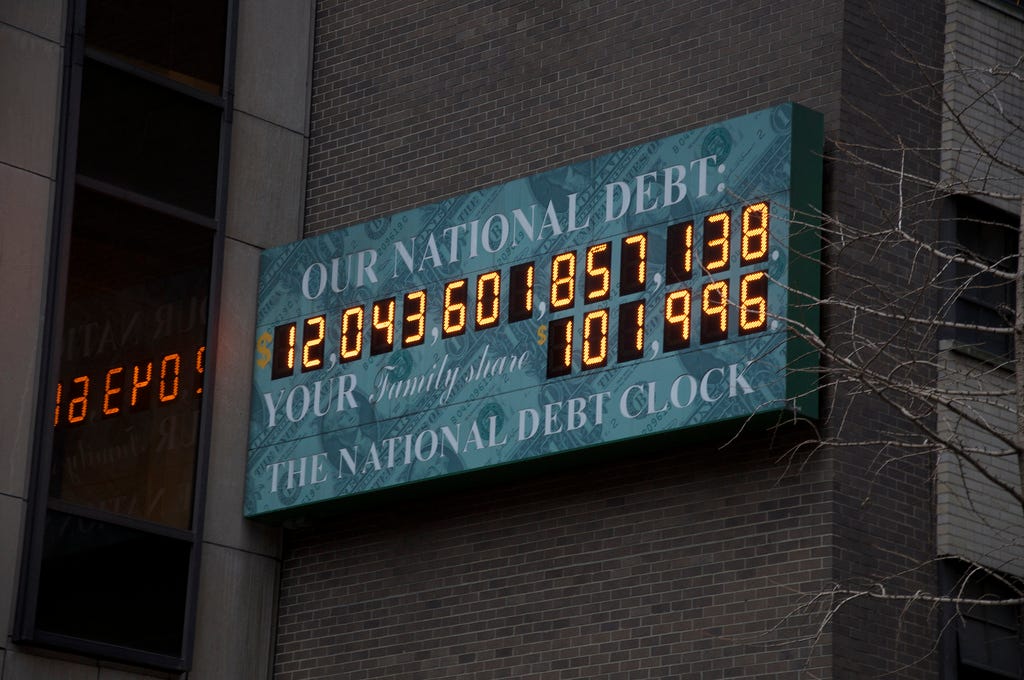

Consider the national debt. If there is a debt, then has to be someone to whom that debt is owed, doesn't there? This is axiomatic. Yet, for some reason, you never hear about that side of the equation, do you? Why is that?

We constantly hear about how paying off the debt will be an intolerable "burden" that we are leaving to "our grandchildren." Won't somebody please think of the children‽

But aren't we also paying that money to our future grandchildren? If not, then who?

Yet, in almost all of the discussions surrounding the national debt, you never hear who that debt is owed to. Can you tell me that information, dear reader? If you cannot, then something very foundational is missing in your understanding of the subject.

I like the way Mark Blyth explains this. He often goes to speak in front of prestigious organizations like the U.S. Naval Academy. During his speech, he asks the members of the audience, "If you had the power to cut the national debt in half, would you?" The members of the audience almost unanimously agree that, yes, they would indeed do so. Wouldn't anyone? Less debt is good, right?

"Congratulations," Blyth informs them, "you've just wiped out half the national savings."

This shows the dangers of not understanding the subject. And these are our purported future leaders!

So the idea that letting people lose their jobs or become homeless today because it would place a burden on some hypothetical future generation years from now is, to put it mildly, batshit crazy. It's deliberate, bald-faced lying. Letting the economy fall to pieces will not help future generations. They will be worse, not better off.

By this same outrageous logic, we would have immediately surrendered to the Japanese after Pearl Harbor, because the cost of war would balloon the national debt and leave an intolerable burden to future generations.

In fact, the costs of that war did indeed balloon the national debt to unprecedented levels relative to GDP (which was itself invented for the purposes of calculating production during the war). When the war was over, the national debt was larger than the entire U.S. economy. It was much larger in absolute terms than it is today. Note that the national debt is always a ratio, not an absolute number: the size relative to the economy.

Did future generations suffer? Who were they? Oh, that's right, they were the Baby Boomers who were the most prosperous generation in the nation's history, before or since.

Refusing to spend money to help suffering Americans right now to protect future generations is a cruel, bald-faced lie. People are guaranteed to die because of it. It is social murder on an industrial scale. People like Mitch McConnell will be responsible for the social murder of a large number of American citizens as surely as Joseph Stalin was responsible for killing his own people.

I'm being deadly serious here. That's the insidiousness of market capitalism. Because social murder is passively—as opposed to actively, such as herding people into labor camps—carried out under market capitalism, we are fooled into thinking that it doesn't exist. And yet people have needlessly been killed under capitalism just as surely as they have been under communism, even if we can quibble about the numbers. And let's not forget that communist countries were often underdeveloped autocracies in the midst of civil wars, unlike capitalist countries which have no such excuse. Murder is murder, period, and it's always wrong.

Another trick is taking the national debt and dividing it by the total number of people in the country and scaring them by saying, "here's your portion of the national debt!"

Paid to whom? By whom? When? Why doesn't anyone ever ask these simple questions?

Another trick is comparing the national debt to GDP and saying that "the debt is larger than the entire economy!" "We're doomed!!!"

Anyone trying this tactic is clearly an idiot and everything they subsequently say should be called into question. I can prove this. Loans are paid back over time. Almost every home owner has a mortgage debt that is larger than their annual income. Are all of them doomed? It's another classic bone-headed mistake: confusing stocks and flows. Plus, as the "debt" is paid back, the economy expands because new money is being added into the economy.

So if someone is spewing this nonsense, why are you listening to them?

Note also that almost every country in the world is simultaneously in debt. How can that be? To whom is all this money owed? Another planet? Mars? Alpha Centauri?

Yet no one ever asks these questions!

The asset and liability duality is important to understanding banking. You should understand by now that when a loan is taken out, it creates brand new money. This means that when lots of new loans are made, lots of brand new money is being added to the economic system. In fact, most new money is created via this method. I don't have time to go into detail to prove this—that's a topic for another post.

Because banks create new money by making loans, banks are important economic players in their own right, and not simply intermediaries between buyers and sellers. Remarkably, this is left out of most economics textbooks, which is why banking crises have consistently been missed by professional economists.

When you take out a loan, you have a liability to the bank in the amount of the loan. You paying back that loan over time is considered to be an asset for the bank. The asset/ liability relationship effectively creates new money.

The opposite happens when you deposit your money with the bank. The bank has a liability to you in the amount of your deposit. You have a corresponding asset in the amount of the bank deposit—the money the bank owes to you. So in the case of a deposit, the bank is effectively in debt to you, rather than the other way around.

This is how it actually works. You're not getting someone else's money when you take out a loan. People tend to think of deposits as a big ol’ pile of cash sitting around in a vault, and when the bank makes a loan, it scoops up some of that cash and hands it over to the guy taking out a loan. Or else they think that their deposit at the bank is a wad of cash that the bank sticks in a safe somewhere just waiting for you to return and claim it later. Kind of like Scrooge McDuck’s money vault.

Nope, that's not how it works. It's all just transactions on balance sheets. As Nathan Tankus points out, "it's the payment system itself that is money."

To manage the market economy, government fiddles with the interest rate, which is basically the price of money. When it wants more money in the banking system, it lowers the cost of borrowing it by lowering the interest rate. When it wants less money in the banking system, it raises the cost of borrowing by raising the interest rate. It does this not by decree, but by buying and selling treasury securities, but we don't need to get into the details of that. (for simplicity I’m omitting which interest rate—the rate for overnight loans between the banks)

Another potential way of injecting money into the economy is for the government to spend money directly. The potential $2,000 checks are an example of that, but there are many different ways this is done. The government has a lot of people on its payroll, including everyone in the military. Or else it pays people in the private sector to do things for it, like design and build a new courthouse, or a new fighter jet, for example.

The government spends by adjusting numbers upwards in accounts. It taxes by adjusting numbers downward in accounts. It doesn't print up a bunch of bills made out of paper. It doesn't mint a bunch of new coins. It doesn't check if it has enough dollars sitting around in a vault somewhere, or in various checking accounts. It's not like money changing hands at your local bodega for cigarettes. It's keystrokes.

Note that no one—and I mean virtually no one—talks about inflation when tons of new money is added to the economy through the expansion of private debt (i.e. lots of new loans being made). Yet it seems that, for some people, if government spends anything—anything at all—hyperinflation is always and forever imminent.

This is, to put it bluntly, sheer and utter bullshit. It's absolutely politicized. Why would money that the government spends be inflationary, but the exact same amount of new money added to the economy through private loans not be inflationary? It doesn't make any sense.

In fact, research has conclusively shown that every single economic crisis in history has been caused by the rapid expansion of private debt, and not by an increase in government spending or the national debt. An increase in the national debt has never—repeat, never—caused a financial crisis by itself, certainly not in the United States. This is another reason why the moral panic around it is deceitful and immoral.

It's also worth mentioning that there has never been even a single case hyperinflation in the core economies since the end of the Second World War. I'm referring to the Group of Seven (G7) nations which use dollars, Euros, Pounds or Yen. It's simply never happened! Note that high inflation is not hyperinflation!

Every single episode of hyperinflation since World War Two has been in peripheral economies, particularly in Latin America and Subsaharan Africa. And in these instances, it is always because (a) large amounts of debt are denominated in a foreign currency; (b) governmental breakdown; and (c) a major loss of productive capacity; or some combination of these things. Hyperinflation, when it does occur, is a political choice, not an unexplained economic event. It's usually done to try and pay back foreign loans or expand an economy that cannot do so because of a loss of productive capacity or governmental incompetence.

Yet if you go online, you'll see that every anonymous poster is utterly convinced that the destruction of the dollar is imminent and that our money is sure to lose all of its value any day now. Some people have quite literally been predicting this for the last twenty-plus years without any apparent loss of credibility.

Why do people believe this shit? And why the fuck does anyone still listen to them?

I suggest you stop.

It also shows the lies and disingenuousness surrounding the health care debate. The current status quo is that health care is currently around 17 percent of GDP—nearly 1/5th of the economy. That is, nearly one out of every five dollars is spent on health care services in the United States today.

In most other countries with government-funded health care systems, that's closer to around ten percent: 1/10. That is, one out of every ten dollars get spent on health care services instead of one out of every five.

Where do people think the money to pay for the private system is going to come from? Are hospitals allowed to print money? Last time I checked, they weren't. So the deficit is going to up either way, because the money has to come from somewhere. It doesn't make sense that a single-payer system run by the government would be inflationary at 1/10th of GDP, while our privately-run health care system would not be inflationary while costing a whopping 1/5 of GDP.

What this shows is that a single-payer health care system would actually save money and ultimately lower the national debt. People will cry to the heavens about the trillions of dollars the government would have to spend to provide health care to every single American, but it will ultimately end up issuing even more money into the economy to pay for our current privatized clusterfuck of a health care system that leaves millions of people uninsured even during a pandemic. It's just that under the current status quo, a lot of that money is going to end up in the pockets of wealthy private donors who disseminate scare stories about "the deficit." Even the so-called "leftist" party in the United States promulgates this idea.

Finally, the fact that one person's spending is another’s income is important for understanding why the macroeconomy is different from the economics of a person's own household. Macroeconomy refers to the sum total of all businesses and households in the economy rather than just a single one. In business school you'll be taught how to manage and run a business, but obviously not all businesses at once! The management of a single household or business we can refer to as microeconomics. Economics, then, is comprised of both of these things.

If I spend money, I've lost it. From my standpoint, it's gone. It's no longer a part of my household or business. Presumably I've gotten something in return for my money. Hopefully it was worthwhile.

But in terms of the economy as a whole, when one person spends money, another person or household receives it, so there is no net loss! This alone should convince you that macroeconomics is a very different animal than managing your own personal finances.

Yet despite this, they are constantly conflated by the average internet loudmouth. People think that government should be run "like a business," and that it's just like managing your own personal finances—complete with balancing the checkbook at the end of every month. Insane!

Lately, when I hear people describing themselves as "economic conservatives," what I really hear is "I am ignorant about how money actually works;" or "I misunderstand economics and think that governments are like households;" or my perhaps, "my economic beliefs are based on moral intuition and folk beliefs rather than actual knowledge."

Of course, this picture becomes a bit more complicated once you start bringing other countries into the mix. Because this is a short letter, I'm not going to do that right now. But even if I did, you would see that the basic principles still hold, just with a few minor adjustments.

The binary principle is important here, too. For example, for every exporting country, there must also an importing country. That is, not every country in the world can simultaneously pursue an export strategy at the same time. This, in turn, means that some countries are always going to have trade deficits no matter what. Some countries are going to be net exporters and some are going to be net importers.

I’ll leave it there for now.

Hopefully 2021 will be a slight improvement over last year. Can't get any worse, can it? Where I am it's very cold, dark, and grey, and we're getting socked with another 5 inches of snow on top of the 9+ we received just two days ago, so I'm totally depressed and utterly miserable. Hopefully you're doing better wherever you are.

Clappity, Chad, clappity! The Money Problem needs to be clarified at every turn!

—"Perry",

Your Ad Attacker

This is really good. Thanks. My only complaint is that you keep asserting that "Nobody asks this question!" when I've been asking for years!