So what really was the cause of our prosperity during the Long Twentieth Century? What really lay behind the Golden Age of Capitalism? If we don't want to be as oblivious as cargo cultists, we should come up with a better explanation.

What I'm starting to wonder is, maybe it really was just about the oil after all!

I was blown away by this chart, which shows the price of oil over time in constant dollars. That last part is critical. This is what it cost you to buy a barrel of oil in real terms relative to your income, not distorted by inflation:

The major takeaway from this chart is this: the highest price for oil before 1973 was lower than the lowest price of oil after 1973. (The nominal price is even more bonkers). And prices were far more stable to boot.

That's staggering! I don't know why we don't talk about this more. The single exception to this (besides the pandemic) seems to be a brief period in the late 1990s. And—what should be to no one's surprise—that period also happened to coincide with the last booming economy to most people's recollection. Moreover, there are almost vertical rises in the 1970s coinciding with the twin Oil Shocks, and an almost vertical drop coinciding with "Morning in America" (although technically that was a bit earlier, but prices were still on the downswing). There’s a spike that cost the elder George Bush his job in 1990, followed by the “Clinton Boom” when the budget was in surplus for the last time. And the all-time high seems to be when the global economy melted down in 2008.

It seems like this almost perfectly correlates to periods of economic expansion and recession. Furthermore, the period of cheap oil perfectly overlaps the Golden Age of Capitalism (also known as the Long Boom) that we've been talking about from 1946 to 1973.

Is it really just that simple?

I've been thinking about that since the latest rise in oil prices. Oil spiked to five dollars a gallon a short while ago, prompting a round of panic and finger-pointing. People slapped "I did that" stickers with pictures of Biden all over gas pumps, proving once again that people are too stupid to run their own affairs (curiously, the same people didn't give Biden any credit when gas prices went back down again).

That episode should have made it clear that, ultimately, it really is still all about the energy. Gas prices are extraordinarily important to the U.S. economy. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the closure of the Nord Stream pipeline, and the recent price hike by producers have all contributed to an ongoing "energy crisis" in Europe which is clearly the prime mover behind inflation and the subsequent cost of living crisis, which is currently spreading across the globe.

So I ask again: was peak oil cancelled, or just postponed?

A Brief History of Oil

The first commercial oil well in the United States was the Drake Well in Pennsylvania, near the center of U.S. industry at the time. That was in 1859, suspiciously close the beginning of the Long Twentieth Century. Originally, gasoline was a byproduct of kerosene production for lamps, and thus it was considered to be a waste product. Then along came the internal combustion engine.

The birth of the modern oil industry began with the Spindletop oil field in Texas in 1901. As Wikipedia notes, "Gulf Oil and Texaco, now part of Chevron Corporation, were formed to develop production at Spindletop."

This may come as a shock, but for most of the twentieth century, the major problem with oil was not that it was too expensive, but that it was too cheap. There was too much supply relative to demand, making it hard for oil companies to make a sufficient profit. To that end, all sorts of new uses for oil had to be developed to drive up the demand to match the supply. As Thorstein Veblen quipped, “invention is the mother of necessity.” That's where suburban sprawl and the U.S. Interstate Highway System came from in the 1950s and 1960s. Having a car become an American birthright.

For the next several decades, the so-called "seven sisters" pretty much controlled oil production worldwide and set the price of a barrel of oil. The OPEC cartel was formed in the 1960s, inspired by—believe it or not—the Texas Railroad Commission. In the early 1970s, a couple of things happened in rapid succession:

1.) The United States reached the peak of conventional oil extraction.

2.) The OPEC countries decided they were tired of basically giving away the substance that Western industrialism depended on, and wielded the power of the cartel to raise the price.

The peak of domestic U.S. oil production meant that the major industrial powers, including the United States, had no choice but to buy from the less-developed countries around the world that still had plentiful oil in the ground, the majority of whom were members of OPEC. This was exacerbated by conflicts in the Middle East. The Oil Embargo hit at the beginning of the 1970s when Arab countries decided to use the "oil weapon" in retaliation for support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The result was that, "By the end of the embargo in March 1974, the price of oil had risen nearly 300%, from US$3 per barrel to nearly $12 per barrel globally; US prices were significantly higher." (Wikipedia) At the end of the 1970s the Iranian Revolution ushered in a Second Oil Shock. Even though oil production didn't decrease as a result of the Revolution, speculation by spooked traders drove the price of oil to new highs.

This had the effect of reversing the previous several centuries of history where the wealth of the global South flowed to the industrial economies of the North Atlantic. Now the wealth of those economies started flowing east once again, in what has been described as "the single biggest wealth transfer in human history." That's when oil sheikhs started buying Rolls Royces and yachts and everything else in sight with their newfound money (as depicted in the 1976 movie Network).

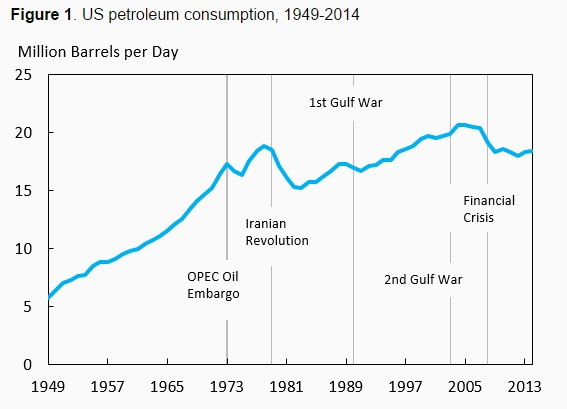

By the 1980s, the OPEC countries had realized they had raised the price of oil too high. Demand for oil crashed as the economies of the industrialized nations of North America, Europe and Asia cratered. Alternatives for using oil started to be developed (such as solar panels, stricter energy codes and electric cars). There was a very real fear that the West would wean themselves off of oil and demand would fall below supply once again. As Wikipedia puts it, "OPEC had relied on price inelasticity to maintain high consumption, but had underestimated the extent to which conservation and other sources of supply would eventually reduce demand." As a result, U.S. oil consumption was roughly in 1980 what it had been ten years earlier in 1970:

That realization led to the great era of moderation where oil prices would be high, but not too high, oscillating in a sort of Goldilocks range. Oil would be expensive enough to keep the oil producers rich, but not so high as to cause recessions and motivate people to start looking around for alternatives. "Swing producers" would step in if the price got too high, and back off if it got too low. Production diversified to regions like Alaska, Canada, the North Sea, and the Caucasus. There was a massive boom in offshore oil drilling. Sustained high prices also provided an incentive to develop new technologies to exploit unconventional oil sources like hydraulic fracturing to get at "tight" oil. As a result of the latter, "the United States became the world's largest crude-oil producer, according to the Energy Information Administration."

It was enough to keep industrialism limping along. But the Golden Age of Capitalism was over.

The Nixon Shock

The Golden Age of Capitalism unfolded against the backdrop of a monetary system known as Bretton Woods after the place where it was developed. It can't be emphasized enough that this system was established 1.) in the aftermath of World War Two when every other nation’s industrial plant lay in ruins; 2.) when every industrialized nation was in debt to the U.S. as a result of war spending; and 3.) when almost all the physical gold in the world was held by the U.S. at Fort Knox. These factors are what made the Bretton Woods system possible. The United States was, in effect, the global economy.

But by the early 1970's, the world had changed dramatically and this system was no longer viable. This article from Yale Insights does a good job in explaining not only what happened then, but more importantly, why it happened (my emphasis):

At the end of the Second World War, there was literally no functioning global economy, so nations got together to create a new trading system and a new monetary system. That monetary system was devised in a town in New Hampshire called Bretton Woods, so it was called the Bretton Woods Agreement. One of the key elements was that the dollar would be pegged to gold at $35 an ounce. Other central banks could exchange the dollars they held for gold. In that sense, the dollar was as good as gold. Every other currency had a fixed exchange rate to the dollar.

They established the dollar-gold standard to create some predictability and stability for global commerce. For the next 25 years, it was a tremendous success. The dollar became the global currency. Everyone was happy to hold it, in large part because they could exchange it for gold if they had any doubts about its value. It was part of the phenomenal recovery from the war in Europe and Japan. It also created enormous economic prosperity in the U.S., all through the ’50s and ’60s.

When the Nixon administration came into office in 1969, they realize that the world economy had grown very, very big. Everybody wanted dollars, so the Federal Reserve was printing lots of dollars. As a result, there were four times as many dollars in circulation as there was gold in reserves.

The rate of $35 for an ounce of gold was good in 1944, but it hadn’t changed, so by 1971 the dollar was really overvalued. That meant imports were very cheap, and exports were very expensive. We experienced our first trade deficit since the 19th century. We were experiencing employment problems. For the first time, the U.S. started to talk about losing competitiveness.

In the broadest sense, the United States couldn’t uphold all of the responsibilities that it inherited after the Second World War. For decades, the U.S. was so predominant that we could help everybody; we lifted the world economy and didn’t worry about the domestic economy because it was so strong. Nineteen seventy-one was the year the U.S. began to understand the Marshall Plan mentality was over.

On top of all that, there was the beginning of inflation. If it continued long enough, dollars would be worth less than they were before. The Nixon Administration was afraid that other countries were going to ask for gold and the U.S. wouldn’t have it. That would have been an enormous humiliation and a breaking of their commitment to exchange gold for dollars.

What the U.S. really wanted was some way to devalue the dollar, but because it was pegged to gold, the administration couldn’t do that.

How the ‘Nixon Shock’ Remade the World Economy (Yale Insights)

It's important to point out that gold was held exclusively by central banks in this system and was only used to settle balance of trade payments. Gold hadn't been privately held since the Great Depression and no one actually used gold for anything in the domestic economy anymore (i.e. it was already a fiat currency). It was simply a way to ensure faith in this system for foreign countries.

Simply put, the United States had basically all of the world's gold in 1946 and was the only industrial manufacturing power left standing. By 1971, other countries had largely rebuilt (notably Germany and Japan), and gold started flowing outward to those countries as our trade balance worsened because they were grabbing an ever-larger share of the global economic pie (France was particularly insistent on getting paid with gold). This meant U.S. no longer had enough gold reserves to cover the amount of dollars that were out there circulating in the world and sitting in bank accounts (as only the U.S. dollar was convertible to gold). The import situation could not correct itself because the peg meant that the dollar was overvalued relative to other currencies like the Deutschmark and the Yen. Severing the link was the only logical and rational option.

There's this crazy website I constantly see posted online all the time called What Happened in 1971?, I think (I won't do it the dignity of linking to it). It's put out by a bunch of libertarian Bitcoin enthusiasts to imply that money isn’t "real", or some such nonsense. In fact, changes in the real global economy ended the Bretton Woods system, notably the reconstruction of the global economy in the aftermath of the War. Inflation caused the end of Bretton Woods, not the other way around. Inflation was ultimately due to oil, and was about to accelerate to staggering new highs (which would have made the system even more untenable).

So, no, it was not a evil conspiracy to replace gold with "worthless pieces of paper," and it did not cause the destabilization of the world economy; in fact, it stabilized it. It was a logical response to a system that made sense in 1945 but didn't make sense in 1971. What happened in 1971? "Nineteen seventy-one was the year the U.S. began to understand the Marshall Plan mentality was over." For a further debunking of this baloney, see this Reddit thread: https://www.reddit.com/r/AskEconomics/comments/sccs74/so_wtf_happened_in_1971/

But what it did contribute to was the establishment of the new economic philosophy known as neoliberalism (although it wasn’t called that by its proponents). That’s what was actually behind the explosion of inequality, the financialization of the economy, and the export of jobs from industrialized heartland countries.

Neoliberalism presided over a new age of slower growth after the Golden Age of Capitalism. In this new era of slow growth, the only way to keep profits high and the fortunes of the wealthy growing was, in effect, to transfer wealth from the bottom of the social pyramid to the top. Neoliberalism developed a number of tools to do that, from offshoring, to financialization, to rent-seeking, to income tax reductions, to union-busting, to privatization. And that's exactly what it accomplished. Unlike the previous transfer, which transferred wealth from West to East, this time it transferred wealth upward—from the bottom 90 percent to the top one percent. And it exceeded even the magnitude of the previous transfer, to the tune of around 50 trillion dollars:

Inflation, the end of Bretton Woods, the rise of neoliberalism, and the gutting of the American middle class might all seem like unrelated phenomena. But if I'm right, then it really was the end of cheap oil which underpinned all of those things. And it's been relatively expensive ever since.

And that's where we are today.

The End of the Long Twentieth Century

I've been listening to Nate Hagens' podcast. One thing he always points out is that a single barrel of oil, in terms of energy, contains the equivalent of around four and a half years of human labor, yet we only pay roughly 90-100 dollars for it. That’s the bargain which sustained the modern world. It's fairly obvious to me that back when we only paid around three dollars for that same barrel there was even more of an economic bonanza. And it also seems obvious to me that this was the actual cause of the Golden Age of Capitalism, and that everything else is a smokescreen.

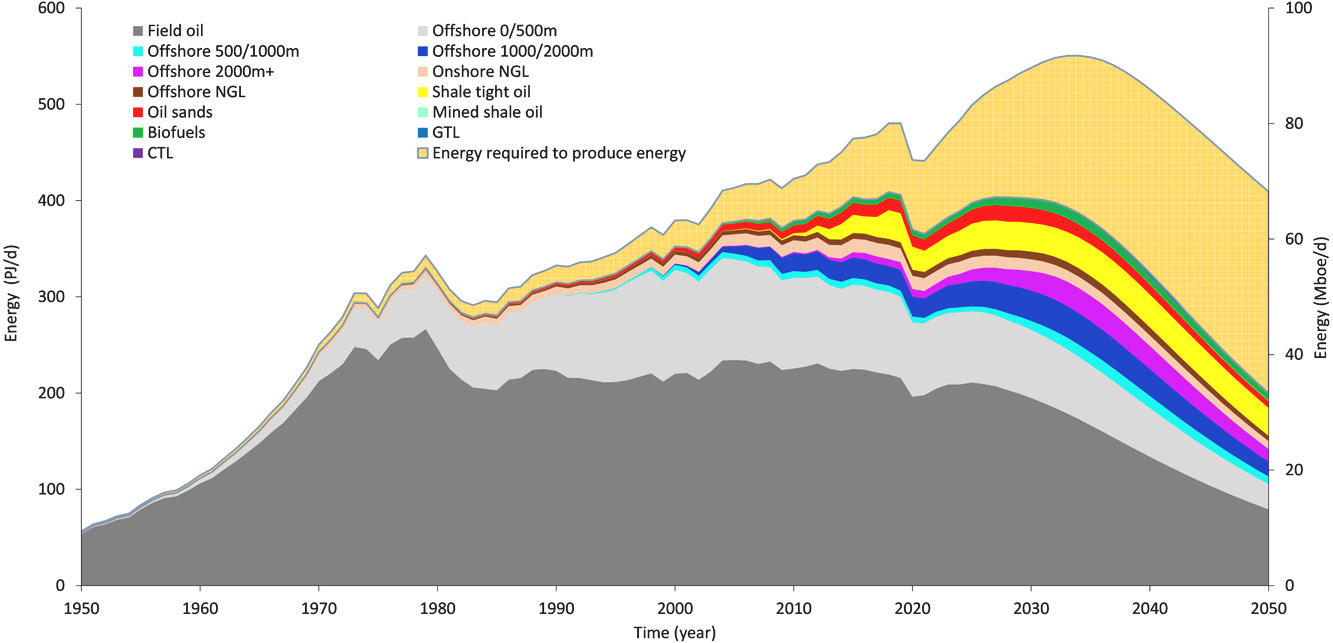

Nate thinks that we may have hit the peak of conventional oil production in 2018. It's important to distinguish between the peak of oil production, and the peak of conventional oil production. Conventional oil is the cheap and easy-to-get stuff. Unconventional oil depends on high technology and high prices, otherwise it stays in the ground due to the stark realities of accounting. It is unconventional oil which has forestalled peak oil. But it has not forestalled price increases and unstable production swings, and those have been an integral part of the global economy for the past two decades. This chart tells the story:

The dark gray is conventional oil. The light gray is offshore oil. The party seems to have ended around 1980, with a blip in the 1970s, consistent with the idea of the Long Boom. While we’re a bit higher today (with a much larger global population), we’re sustained by a “rainbow” of energy sources, including offshore oil, shale oil, tight oil, natural gas, tar sands, biofuels, and so forth. Note the large mustard-yellow color going forward after 2020. That’s the energy required to produce energy, or EROEI (energy return on energy invested).

Economist Brad DeLong, from whom I took the date of 1870 and the idea of a “Long Twentieth Century,” has a new book out describing the exit from what he describes as the Malthusian world we lived under for most of human history. By crunching the numbers, he argues that we exited this world only around 1870. That’s about a hundred years after the first commercially-viable steam engine, ten years after the first commercial oil wells were drilled, and a hundred years before the first oil shock.

Amazingly, however, he does not mention oil or fossil fuels as the primary reason behind this (although it does get a brief mention as contributing to the stagflation of the 1970s). Instead, he attributes it to the scientific method, modern corporations, industrial research labs and globalized markets. But really, these things either found new ways to harness the power of fossil fuels (corporations & research laboratories) or were enabled by their exploitation (complexity, refrigeration, and long-distance transport):

Economic historians debate, and will debate as long as there is a human species, exactly why the change came in 1870. They debate whether the change could have come earlier—perhaps starting in Alexandria, Egypt back in the year 170 when Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ruled in Rome, or in the year 1170 when Emperor Gaozong ruled in Hangzhou. They debate whether we might have missed the bus that arrived in 1870 and still, today, be trapped in a Malthusian steampunk, gunpowder-empire, or neo-mediæval world.

But we did not. A lot of things had to go right and fall into place to create the astonishingly-rich-in-historical-perspective world we have today. Three key elements—modern science and the industrial research lab to discover and develop useful technologies, the modern corporation to develop and deploy them, and the globalized market economy to deploy and diffuse them throughout the world—fell into place around 1870.

Our Ancestors Thought We'd Build an Economic Paradise. Instead We Got 2022 (Time)

No mention of oil or fossil fuels whatsoever. Why 1870? It's a mystery!

It's my thesis that the rising cost of energy—created by geophysical reality—mixed with the increasing environmental destruction caused by energy extraction and use—including to earth's atmosphere—are causing a double whammy to the real economy of bits and atoms and molecules. Rising energy costs are being amplified by real-world conditions like droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes, as well as new epidemic diseases affecting plants, animals and humans, and these are what are causing inflation, not "government money printing." We can add environmental destruction and the depletion of resources like fresh water and minerals to that list. And seeking to cure all of this by manipulating interest rates (or even worse, with Bitcoin!) is basically the modern version of a cargo cult. It's a fundamental misattribution of how we got here.

I mentioned at the beginning of this series of posts that the world is increasingly looking like the world that I (and many others) envisioned in the face of peak oil. One of those predictions was chaos and political unrest globally. Well, have a glance at recent headlines:

Fuel protests gripping more than 90 countries (BBC News)

A year of hunger: How the Russia-Ukraine war is worsening climate-linked food shortages (Phys.org)

While these all may seem like unrelated phenomena, maybe it really does come down to the same fundamental thing in the end. To crib from the poet Rilke, "Do not be bewildered by surfaces; in the depths everything becomes energy..."

It’s also leading to the rise of things like ethno-nationalism, fascism, and various other authoritarian schemes. While I disagree with DeLong on many things, I agree with him on these points (my emphasis):

...the potential replacements today for the Neoliberal Order appear massively less attractive than it does. Whether on their own or mixed with surviving Neoliberal remnants, ethno-nationalist populism, authoritarian state surveillance capitalism, or out-and-our neo-fascism are all frightening. And the problems we face are frightening as well: Global warming, ethno-national terrorism on all scales from the individual AR-15 to the Combined Arms Army, revived fascism, techno-kleptocracy—at all of these new and very serious problems that will mark the 21st century.

We have not resolved the dilemmas of the 20th century—as is shown right now most immediately by the failure of governments to manage economies for equitably-distributed non-inflationary full-employment prosperity. It should not be beyond us to elect governments that can manage the technocratic task of squaring the circle, and getting stable prices, full employment, rapid productivity growth, and an equitable distribution of income. Yet somehow it is...We need to think harder, much harder, about how to use our immense technological powers to build a good society.

The problem is that the only real way to solve those problems is anathema to economists like DeLong, who doesn't even seem to understand the role energy plays in creating our economic surplus. It's anathema to the oligarchs, plutocrats, and opinion-shapers who control our current economic and political arrangements, and the politicians who serve them. If the energy gradient that facilitated industrial civilization is indeed in irreversible decline, then our philosophy must change. If the formerly stable climate that has sustained human civilization for the last ten thousand years has been irreparably altered, then our philosophy must change. If the natural world itself has been irrecoverably and systematically depleted (such as 70 percent of species being wiped out), then we must change our approach to living on this planet. Otherwise, we're all just participating in one giant, worldwide cargo cult. And the boats are not coming back.

"One of the key elements was that the dollar would be pegged to gold at $35 an ounce. Other central banks could exchange the dollars they held for gold. In that sense, the dollar was as good as gold. Every other currency had a fixed exchange rate to the dollar."

Has anything like this ever happened in human history before this? It almost seems like a magic trick that we could tie "fiat currency" (if I'm using the term currently) to gold. We're on the tail end of a crazy one-of-a-kind experiment, if I understand everything correctly.

Truly a very insightful analysis. Thank you for sharing your perspective.