The Triumph of Christianity by Bart Ehrman: Review

How an obscure religious sect took over the world

One of the YouTube podcasts I regularly watch is Bart D. Ehman's Misquoting Jesus podcast. This week, I ran across a column in The Guardian which referenced one of Dr. Ehrman's books which, by sheer coincidence, I just happened to have finished recently, so I took it as a sign to go ahead and write a quick review. Besides, it seems appropriate for the Christmas season. What follows is my usual summary of the book combined with my own thoughts.

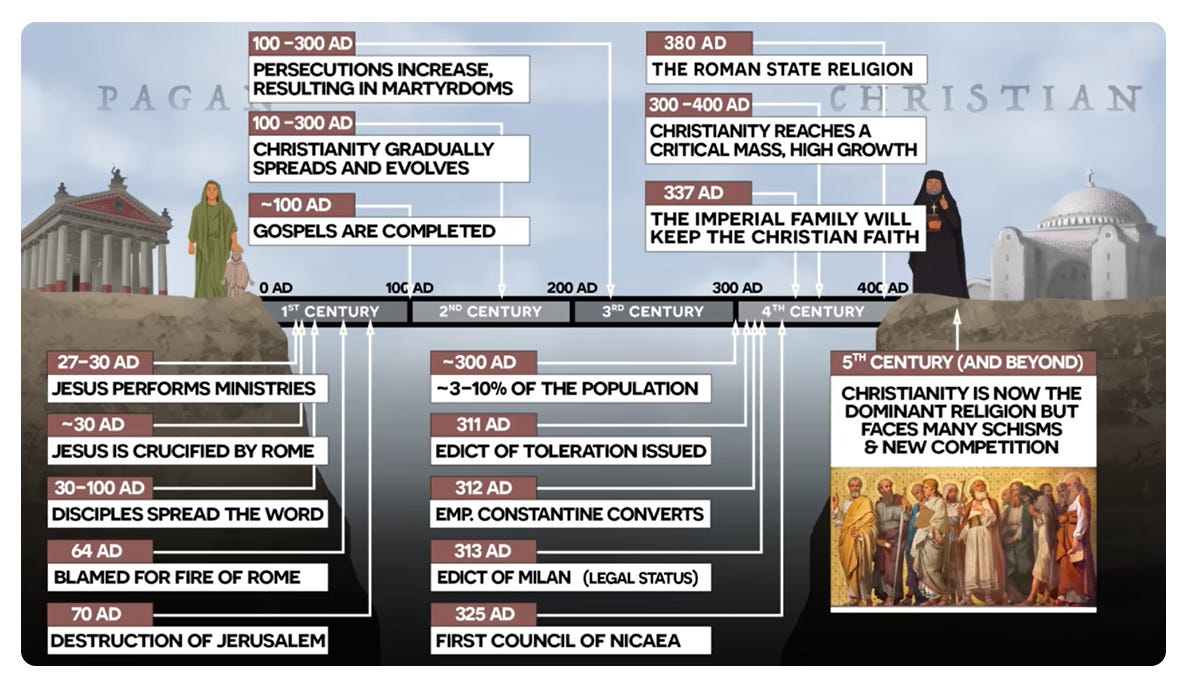

The Triumph of Christianity is based on a simple premise: What started out as a small sect of followers of an obscure Jewish rabbi by the name of Jeshua bar Joseph who lived in the Roman province of Judea and was executed for insurrection eventually become the official state religion of the Roman empire. Moreover, this happened in the span of just a few centuries. How did that happen? How did Christianity go from the verge of extinction to becoming the central, defining religion the Roman world and later European and other cultures? The Guardian article provides a good background:

The Bible informs us that Jesus had 120 followers on the morning of his ascension to heaven. Peter’s preaching swelled the number to 3,000 by the end of the day – but this exponential growth did not continue. After the Jews in Palestine failed to convert en masse, Jesus’s followers turned their attention to Gentiles. They made some headway, but the vast majority of people across the empire continued praying to the Roman gods.

There were about 150,000 Christians scattered across the empire in AD200, according to Bart D Ehrman, author of The Triumph of Christianity. This works out to 0.25% of the population – similar to the proportion of Jehovah’s Witnesses in the UK today.

Then, towards the end of the third century, something remarkable happened. The number of Christian burials in Rome’s catacombs increased rapidly. So did the frequency of Christian first names in papyrus documents preserved by arid desert conditions in Egypt. Christianity was becoming a mass phenomenon. By AD300 there were approximately 3 million Christians in the Roman empire.

In 312, Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. Sunday became the day of rest. Public money was used to build churches, including the Church of the Resurrection in Jerusalem and the Old St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Then, in 380, Christianity became the empire’s official faith.

At the same time, paganism suffered what Edward Gibbon called a “total extirpation”. It was as if the old gods, who had dominated Greco-Roman religious life since at least the time of Homer, simply packed up and left...

The main historical period Ehrman covers is from the death of Jesus, which can be considered the beginning of Christianity, to the conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine in 312 CE. The adoption of the Christian faith by the world's most powerful man at the time can be seen as the key event which led to the eventual triumph of Christianity.

Religion as a joke

Although Ehrman does not mention it in the book, and, as far as I know, he is unaware of the concept, I think memology provides the best explanation for this phenomenon in my opinion.

The idea is simple: we can study the spread and transmission of ideas in much the same way as we can study the spread and transmission of biological traits. This is sometimes referred to as universal Darwinism. But while biological traits only spread vertically from parents to offspring over several generations, ideas can spread horizontally, from person to person, very quickly, in much the same way as pathogens. The biologist E.O. Wilson coined the term culturegen to describe this similarity. However the more popular term is the later coinage of a meme by Richard Dawkins.

This approach has been adopted by cultural anthropologists and historians seeking to understand the expansion and adoption of cultural, technological, and religious ideas. Today, terms like “meme” and “going viral” have become a standard part of our vocabulary due to the near instantaneous transmission of the online world.

The comparison is often made to a joke. Many jokes are surely thought up and told every single day, but most of them never go beyond a small handful of people; that is, they don't have the “traits” that allow them to succeed. But some jokes catch on. Why? Because they have the traits that allow them to spread—in this case, people find them particularly funny, clever, or amusing. And so these jokes go on to be told and retold, spreading throughout a population. That is, these particular jokes “outcompete” their less funny rivals and stick around.

The same can be said for religious ideas. Some have traits which allow them to spread whereas others quickly stagnate or go extinct. Some only “infect” a small group of followers and peter out while others “go viral” and eliminate the competition. The questions is, what makes some religious ideas particularly “infectious” in the way that certain jokes become infectious?

To continue with our pathogen analogy, Christianity could be seen as a sort of “mutation” of Judaism which had itself evolved in its own Middle Eastern crucible over thousands of years. Christianity, then, carried the basic “DNA” of Jewish thought; however, the “mutations” of this particular strain of Judaism allowed it to spread beyond the Jews to the surrounding Gentile population and supplant all other belief systems. Those traits are what allowed the Christian faith to spread exponentially throughout the Classical world and “infect” a large number of followers over several centuries, just like a successful virus (in fact, a literal virus may have contributed to Christianity’s extraordinary spread as we'll see later).

Christian mutations

What were those “mutations?” Ehrman argues that there were three particular traits that were unique to Christianity which led to its explosive growth:

1.) Christianity was an evangelical religion. Christians actively sought to convert other people to the faith. Anyone—not just Jews—could become a Christian. The idea that believing in Christ's message “saved” people and offered them eternal life provided plenty of motivation for Christians to go out and spread the “good news” to as many people as possible (as it still does today).

What scholars call ethnic religions assumed that foreigners would naturally believe in foreign gods, so they did not concern themselves with which gods or entities other people believed. As a result, ethnic religions had no motivation to spread their beliefs beyond their original ethnolinguistic group because there was no concept of one universal message applying equally to all of humanity.

This approach was exemplified by Saul of Tarsus, better known by his Greek/Roman name Paulos or Paulus (Paul). Paul's entire career was dedicated to spreading the Christian faith throughout the Roman world. Ehrman dedicates an entire chapter to Paul and his message. According to tradition, Paul was an itinerant craftsman, possibly a tentmaker or some kind of leather worker, which allowed him to travel and set up temporary shop all over the eastern Mediterranean to convert people to Christianity—especially the Gentiles (non-Jews).

Although Paul started out as a devout Jew and bitter opponent of the Christian sect, he later became its most ardent supporter and effective evangelist. In fact, many scholars consider Paul to be the true author of Christianity as we know it today—in other words, Christianity is the religion about Jesus rather than the religion of Jesus, whose own personal theology was most likely quite different than Paul’s (as Ehrman discusses in other books).

2.) Christianity was an all-encompassing religion. Unlike other supernatural belief systems, Christianity affected every area of your life—how you treated others, whom you associated with, whom you married and had sex with (or didn’t), whom you did business with, how you raised your family, your fundamental morality—every aspect of life was filtered through the lens of Christianity.

Ethnic religions typically did not concern themselves very much with morality or ethics. The gods were mostly indifferent to human suffering and how one behaved towards others—all you could do was to try and propitiate them. In many cases the gods were even capricious and cruel. Sometimes they were even amoral, as with Zeus's habit of sleeping around with mortal women, for example.

The Christian god, on the other hand, was very much concerned with how one behaved due to the religion’s ultimate origin in the Mosaic law of the Hebrews which regulated all aspects of life. Paul gave ethical and moral instructions to the Christian churches in his letters, for example.

Other spiritual traditions extolled the mysteries of existence or appealed to hidden forces beyond our reality, but they typically did any have ethical or moral injunctions, which were instead determined by social custom or cultural practice rather than religious belief.

3.) Christianity was an exclusive religion. According to Ehrman, this was Christianity's most important and effective trait since it meant that every gain for Christianity was necessarily a loss for paganism.

Other contemporary belief systems did not require this sort of exclusivity. If you acquired a belief in a new god or gods, you simply added it to your preexisting spiritual beliefs. If one became, say, a devotee of the cult of Isis, that devotion could sit comfortably alongside preexisting beliefs and practices without any conflict.

By contrast, Christianity asserted that its God was the only true God, all other gods were lifeless idols, and all other belief systems were delusion. This meant that in order to become a member of a Christian church, you had to abandon all your preexisting beliefs and practices. As Ehrman points out, this meant that every convert to Christianity by definition meant one less pagan in a zero-sum game. Put another way, Christianity was a sort of theological invasive species—it literally killed off the competition. It was the kudzu of religions.

Another interesting fact Ehrman discusses is that there was already a clear trend in the Roman world toward the worship of a single god which predated the spread of Christianity. This personal devotion to one particular god did not preclude belief in the existence of other gods; only that one god was more special than all the others. Religious scholars refer to this as henotheism: belief in the existence of multiple gods alongside devotion to one god in particular.

Constantine himself was indicative of this trend. Before he converted he was a devotee of Sol Invictus—the Unconquered Sun—even while acknowledging the existence of other deities in the Roman pantheon. There is some indication that Constantine’s mother had already converted to Christianity before he did, but according to Ehrman, this is uncertain. From this standpoint, Christianity may have come along at the ideal time to take advantage of a preexisting social trend towards commitment to a single deity and took it one step further to true monotheism: the belief in the existence of only a single god.

These three traits, then, are what allowed Christianity to spread throughout the Roman world and displace paganism according to Ehrman. But before we go on, let's consider what people were converting from. What, exactly, was paganism?

Wither paganism?

The term “paganism” was coined to describe myriad polytheistic belief systems and practices around the Roman world which were not confessional and monotheistic like Judaism or Christianity. That is, there was Judaism, there was Christianity—which started out as a sect of Judaism—and all other religious beliefs and practices were grouped together under the umbrella term pagan. Since Christianity was first adopted mainly by cosmopolitan urbanites in eastern Mediterranean cities (hence the titles of many of Paul’s letters), the Latin word for a rural dweller in the countryside—paganus—became the origin of the term.

As Ehrman notes, no one anywhere in the ancient world would have thought of themselves as practicing “paganism” or following any sort of creed the way that Christians professed themselves to be followers of Christ. Ethnic religions passed down their beliefs, rituals, and traditions orally for the most part, often through specialized practitioners like priests, druids, or shamans. While sometimes there were written texts—such as the Sibylline Books in ancient Rome—for the most part there were no sacred texts in the way that the Bible was venerated by Christians. There were no pagan “Bibles.”

In fact, as I’ve written about before, there was not even a term for religion in ancient languages, nor was there such a concept. The closest term might be something like “law,” “practice,” “custom,” or perhaps, “The path.”

Conceptual Fictions Aren't Real

This is more of an observation than any particular insight, but it has always fascinated me that until relatively recently in human history, there was no concept of religion, no concept of society, and no concept of the economy.

Instead, what we now refer to as “religion” in the ancient world was a diverse collection of highly localized idiosyncratic cultural beliefs and practices designed to mollify supernatural forces which were thought to control our destiny from beyond the material plane. These supernatural forces could be personified as gods, spirits, demons, deceased ancestors, or a bewildering array of other supernatural entities and forces.

What they all had in common was that they required humans to continuously provide supplication lest they rain down terror and misfortune upon those who dared to neglect this essential and ongoing duty. The Latin word sacra referred to care and devotion owed to the gods and other supernatural entities. Ancient worship was a highly transactional affair. Offerings were a quid pro quo to keep bad things from happening; otherwise the gods offered very little to their followers—certainly not salvation or eternal life.

How this responsibility was carried out across the Roman world varied from region to region and city to city, and sometimes even from village to village. Religion in the ancient world was a highly local affair, however most provinces were expected to at least venerate the Roman state deities as an act of obeisance. This did not, however, preclude the veneration of other local or ethnic deities which the Romans continued to tolerate.

Ancient religion, then, was less about what people believed than what they did, and what they did was designed to try and assert some modicum of control (or at least the illusion of control) over the forces of chance and nature which affect us all. Building temples, carving statues, making sacrifices, and offerings to the gods were some of the more prominent ways people tried to appease these unseen forces in order to ensure their continued success and good fortune.

Belief in pagan gods was usually not due to some well-thought-out or deep seated belief or commitment. Rather, Ehrman says that the most common reasons for worship were custom—you do what you've always done and what your ancestors did, and conformity—you simply go along with what everyone else around you is doing. These habits formed the basis for pagan religious observance, so there was no reassessment of one’s personal belief system or a “dark night of the soul” when converting to Christianity.

What got the Christians in trouble, then, was never anything they believed but their lack of belief in other gods, and their steadfast refusal to participate in public rituals and ceremonies designed to appease gods in whom they no longer believed. Somewhat amusingly from a modern perspective, this led ancient critics to refer to Christians as atheists. If one refused to perform public acts in service of the gods, they reasoned, then Christians were effectively without gods (a + theos). Not supplicating to the Roman deities, then, could invite catastrophe on a city or village according to pagans, and it was also seen as a kind of subversion by Roman authorities, which is why Christians were occasionally persecuted.

Despite its tendency to proselytize, Ehrman argues that Christianity mostly spread through routine social contact and word-of-mouth. People saw friends, neighbors, business associates, and so forth, converting and how it affected their lives. Because the Classical world was based around extended families and households rather than solitary individuals, when someone converted often their entire household converted as well: relatives, children, spouses, servants, and slaves. It was kind of like an ancient MLM.

What was it about the Christian message that appealed to so many people? In what is sure to be a controversial take, Ehrman argues that what contemporary accounts overwhelmingly tell us—accurately or not—is that people tended to convert because of the Christian ability to work miracles. That is, Christian evangelists worked wonders, and those wonders caused many people—sometimes even entire cities—to adopt the Christian faith en masse and abandon their pagan gods because the Christian god seemed more powerful. These miracles could be healing the sick, for example, or even more spectacular feats like raising the dead or destroying pagan temples. This applied to the apostle Paul himself, who claimed that his ability to work wonders is what attracted converts to his message.

Now, of course, this might sound incredible, in the original meaning of the word. But, Ehman insists, we should not let our modern attitude toward miracles influence what ancient written sources clearly tell us. Whether or not these miracles actually occurred is less relevant than the fact that contemporary people at the time believed that they occurred and, according to eyewitnesses, these miracles are what induced a lot of people to abandon paganism for Christianity.

There are some more believable and less miraculous reasons for Christianity’s rise, however. One popular explanation by some historians and scholars is that the Christian mandate to care for the poor, sick, and dying attracted many followers to its message. Ehrman considers this factor, but ultimately downplays it. However, this is the argument made by the article I quoted above, which notes that the fastest growth of Christianity coincides with the Plague of Cyprian which was possibly some kind of hemorrhagic fever like Ebola. Christian compassion and the idea of a personal, interventionist god made Christianity inherently more attractive to people living under harsh conditions than preexisting “pagan” beliefs:

When your friends, family and neighbours are dying, and there is a very real prospect that you will die soon too, it is only natural to wonder why this is happening and what awaits you in the next life. The historian Kyle Harper and sociologist Rodney Stark argue that Christianity boomed in popularity during the Plague of Cyprian because it provided a more reassuring guide to life at this unsettling time.

Greco-Roman deities were capricious and indifferent to suffering…The old gods did not reward good deeds, so many pagans abandoned the sick “half dead into the road”, according to Bishop Dionysius, the Patriarch of Alexandria. Death was an unappealing prospect, as it meant an uncertain existence in the underworld.

In contrast, Jesus’s message offered meaning and hope. Suffering on Earth was a test that helped believers enter heaven after death…Christians were expected to show their love for God through acts of kindness to the sick and needy. Or as Jesus put it: whatever you do for the least of my brothers and sisters, you do for me.

Emboldened by the promise of life after death, Christians stuck around and got stuck in. Dionysius describes how, “heedless of danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need”. Early Christians would have saved many of the sick by giving them water, food and shelter…As Stark and Harper point out, the fact that so many Christians survived, and that Christians managed to save pagans abandoned by their families, provided the best recruitment material any religion could wish for: “miracles”.

Without these miracles, Romans would not have adopted Jesus’s message so enthusiastically, and Christianity would probably have remained an obscure sect.

The birth of Jesus would probably have been forgotten – if it wasn’t for a plague (The Guardian)

Ehrman devotes a chapter to talking about the persecution of Christians, which he says was greatly exaggerated by later Christian authors. Yes, there were indeed laws passed against Christianity, but there is very little evidence that these laws were regularly enforced or that their punishments were carried out. As Ehman notes, governance was a local affair in the ancient world, and archaic states were often quite weak and had few ways to project centralized authority to ensure that their edicts were followed. Most likely, he says, some Christians were persecuted, but these persecutions were local and sporadic and never amounted to a wholesale suppression of the faith across the empire as is often depicted. Feeding Christians to the lions seems to have been largely made up.

The most significant early Christian persecution was under the Emperor Nero. But, Ehrman points out, this had nothing whatsoever to with Christian beliefs. Rather, Nero blamed the Christians for burning down Rome in order to deflect suspicion from the conspiracy theories surrounding his own role in the event which implied that he had instigated the fire himself in order to initiate an ambitious building program. That persecution ended with Nero.

Endgame

Ehrman then circles around to where he started: the conversion of Constantine the Great to Christianity after the Battle of Milvian Bridge. At the time of Constantine’s conversion, Ehrman estimates that no more than ten percent of the empire's sixty million people may have been Christians, possibly less. That is, the vast majority of the empire’s inhabitants were still pagan. However, Ehrman shows that, when plotted on a graph, the growth of Christianity during these first three centuries follows a classic exponential curve despite comprising a minority of the citizens at the time of conversion. But since Christianity started out with only about a hundred or so followers as we saw, it clearly had explosive growth potential on its side.

It is often believed by many people (including me) that once Constantine converted, Christianity became the “official” state religion of the Roman empire and everyone was forced to become Christian as well, almost like flipping a calendar from one month to the next. But that is not the case. In the years that followed, the vast majority of people in the empire continued to worship as they always had while Christianity continued its explosive growth in the background. However, it did mean some significant changes:

1.) Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313CE which enshrined freedom of worship throughout the empire. After this, Christianity became a legal religion which would no longer be persecuted, except for one brief hiccup which we'll mention in a bit. Converting to Christianity conferred legal and political advantages.

2.) Because of the emperor's patronage, money and wealth flowed to Christian churches and church officials. Many new churches were founded and built around the empire at this time, although archaeology has shown that the numbers were probably exaggerated in the sources. Constantine’s mother was instrumental in this effort, traveling to Judea to establish churches and identify the key locations of Christ’s life and death.

3.) Constantine inserted himself into doctrinal affairs. He wanted Christianity to have a unified, consistent doctrine, and as anyone who knows the history of early Christianity knows, there were multiple, competing versions of Church doctrine among ecclesiastic officials. There were almost as many versions of Christianity as there were churches.

To resolve this conflict, Constantine convened the first Council of Nicea in 325 CE which was designed to come up with the definitive statement of orthodox Christian faith. One particular bone of contention was the so-called “Arian heresy,” which concerned the divinity of Christ. The term “heresy” indicates that it was the loser in this debate, however it still stuck around in various areas for a while longer. The Nicene Creed is still the foundational statement for the Christian faith to this day.

After Constantine's death, Christianity hit its last major bump in the road. Constantine's nephew Julian—known as “the Apostate” by later authors—assumed the purple in 360 CE, and Julian hated Christianity. He withdrew imperial support from the churches and supported paganism. However, Julian didn't reign for very long and he promptly died in battle at age thirty-two, ending this final persecution.

Ehrman contemplates what might have happened if Julian had been a long-reigning and powerful emperor like his uncle, or had even reigned for a couple of decades like his immediate predecessor Constantius II rather than just three short years. Might Christianity’s momentum been halted or even reversed? Might paganism have made a comeback? We'll never know. Instead, from this time forward, all future emperors would be Christian until the empire’s ultimate demise in 1453 CE.

The final chapter of the book covers what happened when Christianity finally did become the official state region of the Roman empire under Theodosius the Great in 380 CE. Unlike when paganism was the dominant belief system, once Christians became the majority they engaged in vicious persecution and suppression of all other non-Christian beliefs and practices which became more severe as time went on. Pagan temples were desecrated, statues were melted down, and altars were vandalized. Any sign of earlier pagan beliefs was obliterated. That is, it was Christianity—not paganism—which was intolerant of other religions. It was an early example of the Paradox of Tolerance in action. This leads to a darkly amusing anecdote where some pagans pleaded for tolerance from the Christian authorities by using their own words form previous times against them. Those pleas fell on deaf ears, however.

With Christianity enshrined as the official state religion of the Roman empire, paganism rapidly disappearing, and the majority of people across the Mediterranean world professing Christian beliefs, Christianity's triumph was assured and Ehrman draws the book to a close. There’s a lot more fascinating stuff in the book itself, of course, but we'll end it there.

If you want more information, this Wikipedia article is very good and goes into more depth:

Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation (Wikipedia)

Also see this recent video from Invicta from where I took the image above:

Near the end of this essay, I think you somewhat overstate the case for Christianity as the destroyer of all things pagan:

"Unlike when paganism was the dominant belief system, once Christians became the majority they engaged in vicious persecution and suppression of all other non-Christian beliefs and practices which became more severe as time went on. Pagan temples were desecrated, statues were melted down, and altars were vandalized. Any sign of earlier pagan beliefs was obliterated. That is, it was Christianity—not paganism—which was intolerant of other religions. It was an early example of the Paradox of Tolerance in action."

For a lengthy, alternative view of this controversial and fascinating topic, let me refer you and your readers to this post: https://historyforatheists.com/2020/03/the-great-myths-8-the-loss-of-ancient-learning/

The same author also writes this about Hypatia of Alexandria and all the myths and legends that have grown up around her: https://historyforatheists.com/2020/07/the-great-myths-9-hypatia-of-alexandria/

Sorry, but your claims wildly overstate the active suppression of paganism and the destruction of temples etc. Most temples were simply abandoned or converted to other uses as their former devotees drifted to Christianity. Active destruction by intolerant Christian fanatics happened occassionally, but was very much the exception. Luke A. Lavan and Michael Mulryan, (eds.) *The Archaeology of Late Antique ‘Paganism’* (Brill, 2011) is the standard modern study of the evidence here and the authors are very clear on what it shows:

"“As a result of recent work, it can be stated with confidence that temples were neither widely converted into churches nor widely demolished in Late Antiquity. …. In his Empire-wide study, Bayliss located only 43 cases [of desacralisation or active architectural destruction of temples] of which a mere 4 were archaeologically confirmed.” (Lavan, “The End of the Temples: Toward a New Narrative?” in Lavan and Mulryan, p. xxiv).