Who We Are And How We Got Here - Part 7 - Africa

The human story began in Africa but it didn't end there

There is often a misconception that once a small group of Homo sapiens left Africa roughly fifty thousand years ago, Africa somehow became frozen in time and all the major developments happened elsewhere. This was exacerbated by the colonialist mindset that portrayed Africa as a place where "civilization" (always expressed in European or Asian terms) failed to develop and depicted Africans and their culture as "primitive" allowing them to be exploited at will. This mindset sadly prevails even today.

The recognition that Africa is central to the human story has, paradoxically, distracted attention form the last fifty-thousand years of its prehistory...The mistaken impression is that once Africa gave birth to the ancestral population of non-Africans, the African story ended, and the people who remained on the continent were static relics of the past, jettisoned from the main plot, unchanging over the last fifty thousand years. (p. 207)

However, this is very far from the truth. The population of Africa has not remained static and unchanged. There have been a number of migrations and expansions of food-producing peoples across the continent over thousands of years causing the genetic profile of modern-day Africans to be significantly different than what it was thousands of years ago. There has also been a continuous exchange of language, genes and culture between Africa and the rest of the world. Africa has not been static and unchanging, but as dynamic as any other region.

Most of these expansions happened only within the last five thousand years of African history, throwing a "veil" over the deep past. Genetics can help lift this veil.

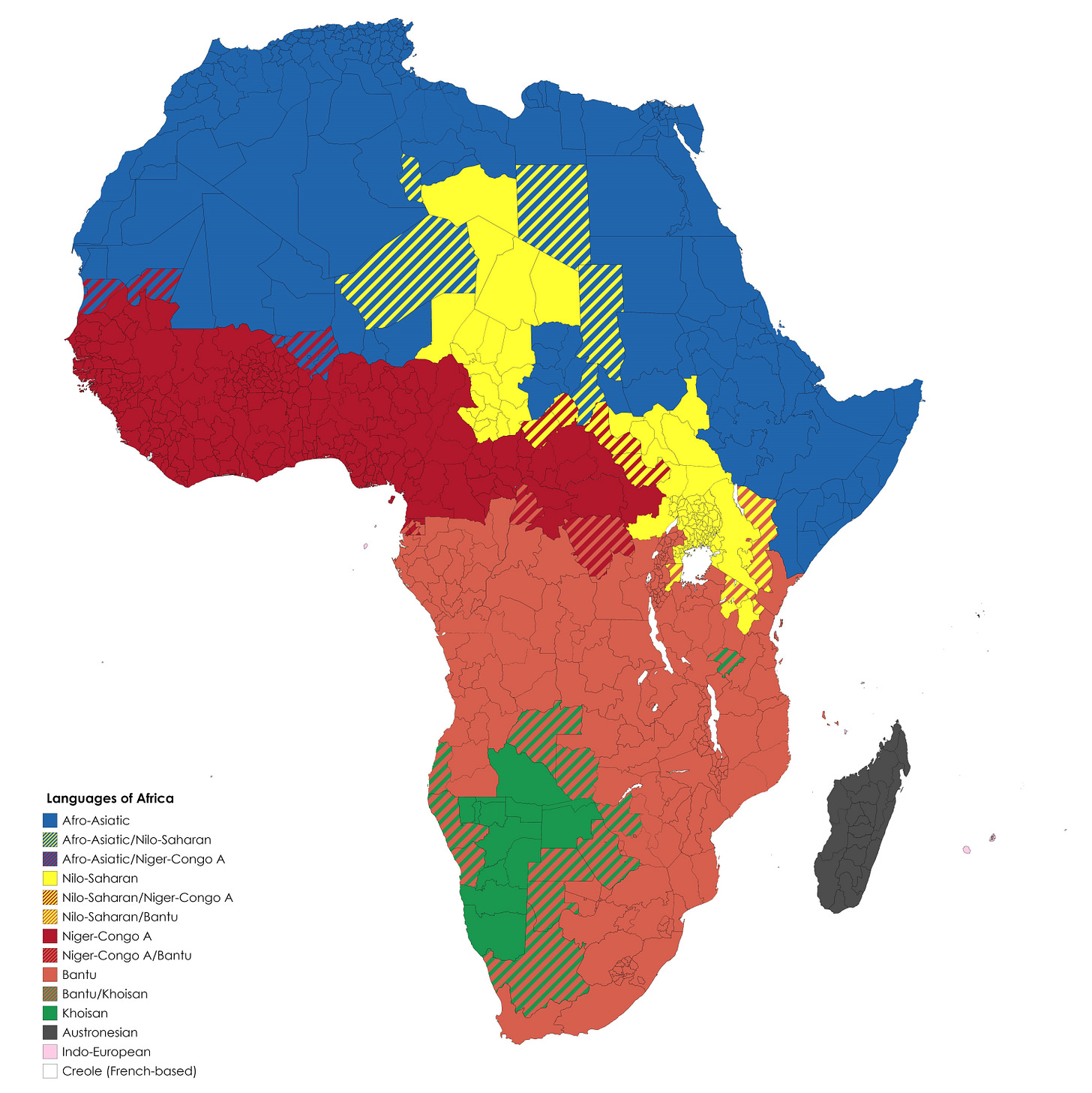

As in many other parts of the world, the expansions of farming and herding peoples within Africa can be documented via the spread of various language families. The four major expansions are as follows:

1.) The expansion of the Bantu-speaking peoples is perhaps the best-known migration, and has had the greatest genetic and linguistic impact in sub-Saharan Africa. The Bantu expansion appears to have originated near the border of Nigeria and Cameroon in west central Africa around four thousand years ago. The Bantu-speaking peoples expanded from this region to the south initially, and then later expanded eastward. These were food-producing peoples who also worked iron. This expansion displaced many of the native hunter-gatherers who lived throughout the southern part of Africa.

Archaeological studies have documented how, beginning around four thousand years ago, a new culture spread out of the region at the border of Nigeria and Cameroon in west-central Africa. People from this culture lived at the boundary of the forest and expanding savanna and developed a highly productive set of crops that was capable of supporting dense populations.

By about twenty-five hundred years ago they had spread as far as lake Victoria in eastern Africa and mastered iron toolmaking technology, and by around seventeen hundred years ago they had reached southern Africa.

The consequence of this expansion is that the great majority of people in eastern, central, and southern Africa speak Bantu languages, which are most diverse in today in present-day Cameroon, consistent with the theory that proto-Bantu languages originated there and were spread by the culture that also expanded from there around four thousand years ago... (p. 214)

2.) The second major expansion is associated with the Nilo-Saharan language group. The Nilo-Saharan language expansion appears to have been driven by farmers and herders originating in the dry Sahel region of the Sahara desert. Nilotic languages are spoken today by cattle-herding people in central and east Africa such as the Dinka and the Maasai.

3.) The third expansion is associated with the Afroasiatic language group. This language family spans both Africa and the Middle East, making it unclear exactly where it originated. The greatest diversity in these languages is found in Ethiopia, raising the possibility that Afroasiatic languages originated there. However, genetics showed that the people responsible for the spread of these languages were Near Eastern farmers who first introduced crops like barley and wheat to East Africa beginning around seven thousand years ago. Semitic languages like Hebrew and Arabic are Afroasiatic languages.

In 2016 and 2017, my laboratory published two papers showing that a shared feature of many East African groups, including ones that do not speak Afroasiatic languages, is that they harbor substantial ancestry from people related to farmers who lived in the Near East around ten thousand years ago.

Our work also found strong evidence for a second wave of West Eurasian-related admixture—this time with a contribution from Iranian-related farmers as might be expected from a spread from the Near East in the Bronze Age—and showed that this ancestry is widespread in present-day people from Somalia and Ethiopia who speak Afroasiatic languages in the Cushitic sub-family.

So the genetic data provide evidence for at least two major waves of north-to-south population movement in the period when Afroasiatic languages were spreading and diversifying, and no evidence of south-to-north migration (there is little if any sub-Saharan African related ancestry in ancient Near Easterners or Egyptians prior to medieval times). (pp. 216-217)

4.) The fourth expansion is the speakers of Khoe-Kwadi languages—languages spoken in southern Africa which feature clicking sounds. It is thought that these languages were spread by herders from East Africa who came to southern Africa after eighteen-hundred years ago and picked up words from the local hunter-gatherer dialect based on shared words for herding in both groups. Click languages were much more widespread in southern Africa prior to the Bantu expansion.

Genetic studies of Khoe-Kwadi speakers found evidence for admixture with a "ghost" herding population sometime between eighteen and nine hundred years ago. This ghost population also harbored a small percentage of West Eurasian-related ancestry.

An analysis of an infant girl dating from 3100 years ago in Tanzania confirms the existence of a population of herders in East Africa from this time who derived most of their genes from East African hunter-gatherers with some admixture from West Eurasians. A genetic sample from a herder who lived 1200 years ago in South Africa showed a combination of the same herding population as the girl from Tanzania along with groups related to local San hunter-gathers, indicating that herding did indeed spread from the Near East into east Africa, and from there spread south to the southern regions of the continent.

The Original Africans

Due to the expansion of food-producing peoples to all regions of the African continent in the last few thousand years, finding out information about the original inhabitants of these regions is more difficult. To help with this, researchers looked at small, isolated populations that are linguistically and genetically isolated from the surrounding food producers—such as the Pygmies of Central Africa, the San hunter-gatherers of South Africa, and the Hadza of Tanzania—and compared them with genome-wide ancient DNA samples from various ancient African cultures.

Researchers identified two deeply divergent lineages which they designated East African Foragers and South African Foragers.

The East African Foragers consisted of three distinct populations. One lived in the area of Kenya and Ethiopia; another contributed large amounts of DNA to ancient foragers from the Zanzibar archipelago and Malawi; with the third being the ancestors of today's Hadza people of Tanzania. The separation date of these lineages could not be determined. The East African Forager population may related to the initial population which left Africa to become the ancestors of all non-Africans today.

A great surprise that emerged from our ancient DNA analysis was there was evidence of a ghost population dominating the eastern seaboard of sub-Saharan Africa that appears to have been largely displaced by the expansion of agriculturalists. This population, which we called the "East African Foragers," contributed all of the ancestry of two ancient hunter-gatherer genomes in our dataset from Ethiopia and Kenya, as well as essentially all of the ancestry of the present-day Hadza of Tanzania, who today number fewer than one thousand.

We also found that the East African Foragers were more closely related to non-Africans today than they were to any other groups in sub-Saharan Africa. The close relationship to non-Africans suggests that the ancestors of the East African Foragers may have been the population in which the Middle to Later Stone Age transition occurred, propelling expansions outside of Africa and possibly within Africa too after around fifty thousand years ago. So the populations that became the East African Foragers had a pivotal role in our history. (p. 221)

The South African foragers were as separate from the East African Foragers as any two lineages outside of Africa today, and furthermore consisted of two distinct lineages that separated from each other at least 20,000 years ago.

South African Foragers are the ancestors of all the southern African groups that speak click languages today. Although the descendants of South African Foragers presently live almost exclusively inside South Africa, there is evidence from ancient sites that they once occupied a much wider area consisting of east Africa as well, where they contributed DNA to a number of ancient peoples who once occupied areas of present-day Zanzibar and Malawi.

Two approximately fourteen-hundred year-old individuals from Zanzibar and Pemba islands off the coast of Tanzania—an island chain that separated from the mainland approximately ten thousand years ago as sea levels rose and thus plausibly harbors isolated descendants of a forager population that lived in East Africa around that time—were a mixture of approximately one-third South African Forager-related ancestry and the remainder East African Forager ancestry.

A series of seven samples from three different archaeological sites in Malawi in south-central Africa, which we dated to between about eighty-one hundred and twenty-five hundred years ago, were part of a homogeneous population that harbored about two-thirds South African Forager-related ancestry and the remainder East African Forager ancestry.

So South African Forager ancestry was in the past distributed over a much broader swath of the continent, making it hard to know where this ancient population originated. (pp. 222-223)

It is well-known that modern humans harbor DNA from a number of archaic human species they encountered during their sojourn outside Africa. But genetics also showed evidence of admixture between at least two different populations inside Africa prior to this migration, and prior to other splits inside Africa.

Western Africans harbor the greatest amount of genetic material from this second, deeply divergent human population, but all humans have some signs of admixture. This admixture must have occurred sometime before two to three hundred thousand years ago which is the approximate date of separation between East African and South African Foragers. Thus, genetic evidence indicates that modern humans are the product of interbreeding between several highly divergent and relatively isolated populations inside Africa in the deep past rather than the result of one freely-intermixing, homogeneous ancestral population.

Perhaps all present-day humans are a mixture of two highly divergent ancestral groups, with the largest proportion in West Africans, but all populations inheriting DNA from both...Because this mixture was closer to 50/50, it is not even clear which one of the source populations should properly be considered archaic and which modern. Perhaps neither was modern, or neither was archaic. Perhaps the mixture itself was essential to forging modern humans...(p, 212)

Ancient DNA data fills in thousands of years of human prehistory in Africa (Science Daily)

Conclusion

That's the end of the book.

There are several additional chapters in which Reich talks about issues like the way inequality is reflected in our genes; sensitive issues surrounding gender and race; and the future of genetic research.

In addition to documenting the human journey, our genes also document social stratification, and even approximately when it occurred, giving insights into social changes that have happened since humans migrated outward into Eurasia and beyond. There seems to have been a couple sharp increases in inequality—one with the advent of agriculture and an even sharper one coinciding with the arrival of the Bronze Age roughly five thousand years ago. This is reflected in the relative diversity between mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal DNA.

It appears as though a small subset of powerful men monopolized access to a much larger pool of women, causing many Y-chromosome signatures to die out. Basically, a lot more women left ancestors than did men. “Star clusters” are patterns where lineages can be traced back to the owner of a particular Y-chromosome at some point in the distant past. Thus, the origins of inequality can be read in the human genome.

The time around five thousand years ago coincides with the period in Eurasia that the archaeologist Andrew Sheratt called the “Secondary Products Revolution,” in which people began to find many uses from domestic animals beyond meat production, including employing them to pull carts and plows and to produce dairy products and clothing such as wool.

This was also around the time of the onset of the Bronze Age, a period of greatly increased human mobility and wealth accumulation, facilitated by the domestication of the horse, the invention of the wheel and wheeled vehicles, and the accumulation of rare metals like copper and tin, which are the ingredients of bronze and had to imported from hundreds or even thousands of kilometers away.

The Y-chromosome patterns reveal that this was also a time of greatly increased inequality, a genetic reflection of the unprecedented concentration of power in tiny fractions of the population that began to be possible during this time due to the new economy. Powerful males in this period left an extraordinary impact on the populations that followed them—more than in any previous period—with some bequeathing DNA to more descendants today than Genghis Khan. (p. 237)

The issues and controversies surrounding the thorny concept of “race” and the distortions and misconceptions surrounding the term are too complex to summarize here and really deserve a post of their own to do them justice. So, too, is what differences in genetics do and do not mean, which is often highly distorted by a number of bad-faith actors. Suffice it to say that these concepts are behind some of the worst atrocities in human history including ethnic conflicts, the slave trade, colonialism, genocides, eugenics, forced sterilization, and Social Darwinism (which, sadly, seems to be making a comeback). Reich—whose father served as the first director of the the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum—discusses these topics in a very thoughtful and insightful way, and his thoughts are worth reading. I wrote my earlier post Three Rules for Understanding with the intention of it serving as a companion to these series of posts. At base, all of us are members of the same family tree.

I actually wrote most of this series many years ago and never published it (which is why I’ve been able to put these out so consistently). I might also put out some earlier “best of” work from previous blogs which hopefully will be new to most readers. Currently I’ve been reading The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow, which I hope to discuss in the near future.

I’ll end with this excerpt from The Invisible History of the Human Race by Christine Kenneally:

If you take any two modern Europeans, no matter how far apart they live, they will likely share millions of genealogical, if not genetic, ancestors within the last thousand years. Still, even though the genealogical tree is much bigger than the genetic tree, it doesn't fan out forever either. Because the number of ancestors in a tree doubles with each generation, any person's tree of possible ancestors grows exponentially and quickly reaches a point where it is greater than the population of the world at the time.

For example, geneticists and historians vary somewhat in their estimate of how long a generation is. Some say twenty years and some say thirty, so let's assume it's around twenty-five years. We'll also assume that there is just one person in the world today, let's say you. In order to arrive at you, there must have been more than a billion people on the planet approximately 750 years ago. Or, to put it another way, about thirty generations ago, there would have to have been roughly 2 billion people in the world, whose children and grandchildren and so forth met and married until one day you appeared. But in fact there were only 400 million people in the world 750 years ago. What this means is that your thirtieth-great-grandparent along one line is probably your thirtieth-great-grandparent along many other lines too. Genealogists call this pedigree collapse.

Pedigree collapse is common in family trees that go back to the nineteenth century and earlier. In many different cultures marriage between cousins was not the exception but the rule. Some scientists...argue that by two thousand to three thousand years years ago, everyone who was alive at that time across the globe was actually a genealogical ancestor of everyone alive today. The argument is a purely mathematical one based on the idea that, because your theoretical genealogical tree would be so massive two to three thousand years ago (over 120,000 trillion ancestors), it must surely include all of the much smaller number of individuals (50 million to 170 million) who were alive in the world at that time. Many population geneticists I spoke to found this to be a completely noncontroversial theory. It wouldn't take long for the networks of relationships in different countries to be altered by the introduction of just one or two transfers from a distant area, connecting all the populations of the world. Others whose work is more engaged with the events of history found the idea implausible: While it's technically possible that the connecting events happened, they believe it is more likely that the world's populations were more completely isolated from one another for a longer period.

A set of common genealogical ancestors doesn't mean, of course, that people today don't have genetic differences. It doesn't mean either that once you go back three thousand years everyone's family history is effectively the same. Even if both you and the emperor of Japan can count the same pharaoh in your family tree, the pharaoh may appear many more times in your tree than the emperor's. Genetic history would not be possible if everyone's genealogical tree were identical a few thousand years ago. If you imagine a great network of ancestors stretching from now back through time, with every person a node in the network, all the people alive in the world three thousand years ago who left any descendants would be significant nodes, because each person alive today could trace a path back to them—but it wouldn't be the same path. Some people would trace thousands of paths back to the same node, while others would trace many fewer.

Curiously, it is often the case that when someone says, "We are all related to Confucius or Boudicea or Erik the Red," the implication is that there is no texture in this history, that if we look back far enough, everyone in our family was the same, so there is little of interest to say about the connection that one person or group of people may have with people from the past. This is not the case. The topology of the human network, in which we are all nodes, is incredibly complicated. While there are points of sameness—perhaps we can all trace at least one connection back to everyone from three thousand years ago—the sameness does not mean that all the other pathways we trace back to shared ancestors do not have great significance. If you start tracking the ancestry of segments of the genome, like the Y chromosome and mtDNA, the picture of shared ancestry becomes much more complicated again. The patterns of all the paths tell us things about history that we might otherwise not know. (pp. 219-221)