Who We Are And How We Got Here - Part 5 - The Americas

Genetics helps uncover the settlement of the Americas

DNA evidence seemed like it would be especially valuable in reconstructing the peopling of the Americas—the last major continental landmass to be colonized by humans. However, this has been confounded by several factors.

One is that genetic material volunteered by Native American peoples has repeatedly been used for purposes other than those consented to by the original donors. This has led to an ongoing atmosphere of recrimination and mistrust between tribal leaders and genetic researchers which persists to this day, with some disputes leading to lawsuits in the past. As a result, many Native American tribes have issued blanket moratoriums on the collection of DNA samples from any of their members even in cases where individual members provide their consent.

Another is that burials of Native American individuals by law (under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) become the property of the tribe they are biologically and culturally related to, rather than the property of the archaeologists who discover them. This means that when ancient burials of Native Americans are uncovered, there is often no opportunity to extract genetic material due to resistance from the tribes leading to a dearth of ancient DNA samples, especially in North America.

A prominent example is the unfortunate case of Kennewick Man, an 8500-year-old Native American burial found in Washington state. For many years it was denied that Kennewick man was, in fact, a Native American at all. This was based on an erroneous analysis of the skull that claimed he was actually related to populations in Japan, Polynesia, and even Europe. A lawsuit was eventually filed by the local tribes which wound up being drawn out over many years in U.S. courts before finally being resolved by a DNA analysis which confirmed that Kennewick Man was indeed related to the native tribes in the area where he was found. And, sadly, this has not been an isolated incident.

The final barrier is that Native American tribes often regard themselves and their ancestors as having always existed in the place they currently occupy, which is what their myths and stories tell them. They have no interest in scientists contradicting those cultural myths and see no benefit in helping them to do so, especially since the deep connection to their land has often been downplayed by expansionist governments wishing to appropriate their territory.

Despite these unfortunate limitations, significant progress has been made in uncovering the process by which the Americas were populated based on the DNA evidence that has been obtained over the years from the inhabitants of both North and South America.

The Coastal Route Hypothesis

It has long been known that the people of the Americas descend from a population that once inhabited a region known as Beringia, much of which lies under water today, but was once a vast grassy tundra populated by wild game, including some of the last woolly mammoths to survive anywhere on earth. What was not known before DNA analysis was the exact composition of the people who lived there, when exactly they first arrived, and their relationship to the subsequent people of the Americas.

The theory long subscribed to by archaeologists was known as the Clovis First hypothesis. This hypothesis was based on spear points discovered at the Clovis archaeological site in New Mexico and a related site called Folsom in the 1920's and 1930's. Spear points similar to those found at Clovis were widely distributed all across North America, usually in association with large game kills, and were for many years the earliest signs of human activity in the Americas. Thus the Clovis hunters, as the people who used these weapons came to be known, were assumed to have been the first people who migrated into North America around 13,500 years ago.

This hypothesis was bolstered by paleoclimatalogical data which indicated that an ice-free corridor had opened up between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets roughly around the same time the Clovis spear points started appearing in the archaeological record. The early DNA evidence also concurred with this timeline.

In recent decades, however, numerous sites have been discovered throughout North and South America indicating an earlier occupation, beginning with the site of Monte Verde in Chile discovered in the 1970's. Parts of this site were reliably dated to 14,500 BCE, well before the Clovis culture of North America. Coprolites from the Paisley Cave site in Oregon indicate occupation of the West Coast of North America south of the Ice Sheets prior to 14,000 years ago. Stone tools found at the The Debra L Friedkin site in Texas demonstrate that there were people living in the Americas at least 2,500 years before Clovis. Some of these sites are on the eastern coast of the United States such as the Topper site in South Carolina and the Page-Ladson sinkhole in Florida.

More recently (2021), footprints were discovered in New Mexico that could be definitively dated to 23,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum, providing the most definitive evidence yet of a pre-Clovis occupation of North America. A group of archeologists have claimed that the Chiquihuite cave in Mexico contains stone tools that are at least 30,000 years old, although this evidence has been disputed.

Fossil footprints prove humans populated the Americas thousands of years earlier than we thought (Phys.org)

The obvious question that arose out of these discoveries was exactly who these people were and how had they had managed to enter the Americas at a time when enormous ice sheets blocked entry into the North American continent.

So far the most prominent alternative theory is that the first humans entered the Americas via a coastal route, moving southward along the ice-free western coast of North America with the help of boats. However, much of this land is now submerged making archaeological confirmation of this hypothesis difficult, if not impossible. A related theory is that the people who traveled along the coast followed a kelp highway which gradually led them southward, and the interior was populated via these coastal regions—known as the Kelp Highway hypothesis.

'Kelp Highway' Hypothesis Rewrites History of the First Americans (Inverse)

The Ancestral Native Americans

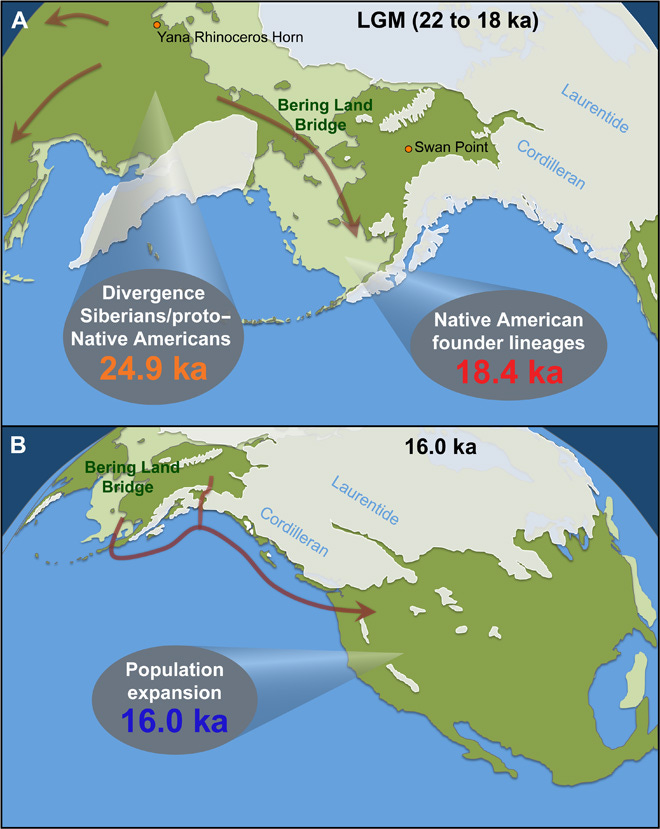

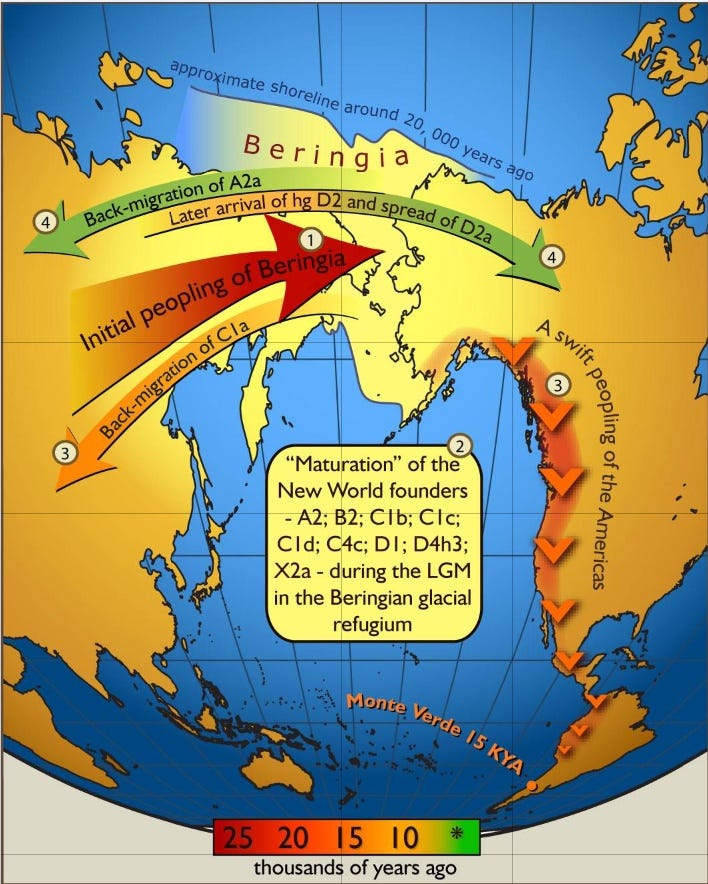

The ancestors of Native Americans began to separate from the larger East Asian population around 35,000 years ago, and were completely separate by 25,000 years ago. Sometime during this period, they had significant influx from the Ancient North Eurasians (who also contributed genes to the Yamnaya as we discovered earlier).

This combination of people formed a population known to geneticists as the Ancestral Native Americans (ANA). The Ancestral Native Americans were initially confined to the vast coastal plain of Beringia which spanned the Asian and North American continents from the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories to the Lena River in Russia. The Bluefish Cave site in the Yukon in modern-day Canada was apparently inhabited as far back as 24,000 years ago.

Evidence indicates that the Beringians occupied this region for a very long time—perhaps as long as 15,000 years—accumulating their own distinctive genetic signatures separate from the surrounding populations. This is considered to be evidence for the Beringian standstill hypothesis. Beringia, then, was not so much simply a "bridge" from one continent to another but a unique region in its own right inhabited by a distinct group of people. Thus, the occupation of the Americas actually goes back as far as the Ice Age.

This population remained isolated in the far north for thousands of years, eventually splitting into two genetically distinct populations roughly 20,000 years ago. One population is known as the Ancient Beringians (AB) and was discovered by examining the burials of a pair of infant girls from the Upward Sun River Site in Alaska dated to 11,400 years ago.

Alaskan infant's DNA tells story of 'first Americans' (BBC)

The other population became the ancestors of all other Native Americans—a population geneticists refer to as First Americans or Amerinds. This was the population that moved south and colonized North and South America.

The First Americans appear to have rapidly migrated south hugging the coastline and gradually moving inland. Once these groups branched off there was little subsequent gene flow between the different populations. Native American populations are more closely related to nearby populations than more distant ones. This is in contrast to Europe or Asia, where ongoing population sweeps mean that present-day ancestry may not reflect that of the deep past. This indicates relatively little movement of people, perhaps due the lack of the horse or the wheel, or the fact that their societies were by-and-large more egalitarian (and consequently less pressure to move elsewhere).

This ancestral population further split into North Native Americans (NNA) and South Native Americans (SNA) sometime between 17,500 and 14,600 years ago. An exception are the Central American Chibchan speakers, who have ancestry from both North and South America reflecting a migration back from South America into Central America. The ancestors of Athabascans (a native Alaskan people) moved north again, possibly around 6,000 years ago, eventually absorbing or replacing the Ancient Beringian population.

This [evidence] suggested to us that the vast majority of Native Americans today, including those from Mexico southward as well as populations from eastern Canada, descend from a single common lineage...Thus the extraordinary physical differences among Native American groups today are due to evolution since splitting from a common ancestral population, not to immigration from different sources in Eurasia...We hypothesized that the "First American" lineage that we had characterized represented the descendants of the first people to spread south of the ice sheets, whether via an ice-free corridor or along a coastal route.

...it became clear to us that the great majority of Native Americans, from populations in Northern North America to down to southern South America, can be broadly described as branches of one tree, forming a sharp contrast to pattern of population relationships in Eurasia. Most populations branched cleanly off the central trunk with little subsequent mixture. The splits proceeded roughly in a north-to-south direction, consistent with the idea that as people traveled south, groups peeled off and settled, remaining in approximately the same place ever since... (p. 172)

The genetic evidence is backed up by linguistics. North American languages are primarily autochthonous languages spoken by the descendants of the original inhabitants of the various regions of the Americas. This situation differs markedly from that of Eurasia and Africa where the expansion of particular groups has created vast “spread zones” of closely related languages.

Anyone looking at a language map of the Americas can see that its appearance is qualitatively different from that of Eurasia of Africa, with dozens of language families restricted to small territories, compared to the vast swaths of territory in Eurasia and Africa inhabited by people who speak closely-related tongues in the Indo-European, Astronesian, Sino-Tibetan, and Bantu language families, each of which reflects a history of mass migrations and population replacements.

The First American expansion seems to have been so fast that the languages of the continent are related by a rake-like structure with many tines extending in parallel to a common root that dates close to the time of the early settlement of the Americas.

So both the genetic and linguistic evidence support a scenario in which many of the present-day Native American populations are direct descendants of populations that plausibly lived in the same region shortly after the first peopling of the continent. This suggests that after the initial dispersal, population replacement was more infrequent in the Americas than it was in Africa and Eurasia.

In the various classification schemes of North American languages, one fact is commonly agreed upon: there are two language families which diverge from all the others. These are the Na-Dene languages spoken among a widely dispersed group in Northwestern Canada and the southwestern United States (including the Navajo language); and the Eskimo-Aleut languages spoken in a circumpolar region stretching from the Aleutian Islands across northern Alaska and Canada into Greenland.

The Na-Dene languages derive from a source language that is considered by linguists to be at most a few thousand years old based on morphological changes. Furthermore, a connection between the Na-Dene languages and a group of languages spoken in central Siberia called Yeniseian was documented in 2008, further strengthening the idea of a more recent migration to the New World.

Based on these facts, linguists hypothesized that these divisions may indicate three separate waves of migration to the Americas at different points in the past. This hypothesis had also been proposed by anthropologists based on dental evidence. A study by Christy Turner of various Amerindian peoples showed that there were three distinct shapes of teeth in the native population of the New World, which could indicate three separate prehistoric migrations from Asia to the Americas.

Genetic evidence has since confirmed this hypothesis. Native Americans do appear to have three deep lineages reflecting three separate migrations from East Asia. The later migrants mixed in with the majority Amerinds leaving traces of their DNA signature in present-day Arctic populations in Alaska, Greenland, and Canada.

Native Americans migrated to the New World in three waves, Harvard-led DNA analysis shows (Boston.com)

The Paleo Eskimos

This notion was bolstered by the discovery that the Chepewyan people of Canada, who speak a Na-Dene language, had a genetic fingerprint that was not shared with other Native American groups. Genetic samples subsequently revealed a relationship between this signature and a 4,000-year old individual from the Saqqaq culture—the first human culture to occupy Greenland.

Based on the linguistic and DNA evidence, this group arrived in North America from Siberia approximately 5,000 years ago and spread rapidly to Labrador and Greenland by 4,500 years ago. These people, who brought the Arctic small tool tradition and the first archery equipment with them to the Americas, were dubbed Paleo-Eskimos (or Paleo-Inuit) by researchers.

It was initially thought that the genetic signature of Paleo Eskimos had died out, but it was later discovered that this lineage persisted in present-day speakers of Na-Dene languages. Paleo-Eskimo ancestry is particularly widespread in Athabaskan and Tlingit communities from Alaska and northern Canada, the West Coast of the United States, and the southwest United States. This strongly indicates that the Na-Dene languages were spread by migrations of people related to the Paleo Eskimos. However, ninety percent of the ancestry of these groups derives from First Americans indicating a long history of admixture with the surrounding populations.

Beginning around 1000 years ago, the ancestors of the present-day Inuit and Yup'ik people, with a sophisticated toolkit including kayaks and harpoons, supplanted the Paleo Eskimos across the extreme northern Arctic, eventually expanding as far east as Greenland where they encountered Norse migrants coming west from Europe. This is reflected in the distribution of Eskimo-Aleut language family. By about 700 years ago, the archaeological evidence for the Paleo-Eskimo culture disappears, however the Paleo-Eskimos did contribute genes to Eskimo-Aleut speakers as well. The ancestors of Aleutian Islanders and Athabaskans derive their genetic heritage from an ancient mixture between Paleo Eskimos and First Americans, with about 60 percent of their ancestry coming from First Americans.

Some of the Eskimo-Aleut speakers migrated back into Siberia bringing First American ancestry along with them. They became the ancestors of the Chukchi people who live in far northeastern Siberia. Genetic analysis showed that the Chukchi harbor around 40 percent First American ancestry, and this ancestry is too recent to be a result of the initial spread to the Americas. This culture eventually expanded back into the Americas spreading more recent East Asian ancestry than that which exists in the First Americans or Paleo Eskimos.

Based on the researchers' analysis, Paleo-Eskimos interbred with people with ancestry similar to more southern Native peoples shortly after their arrival to Alaska, between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago. The ancestors of Aleutian Islanders and Athabaskans derive their genetic heritage directly from the ancient mixture between these two groups.

The researchers also found that the ancestors of the Inuit and Yup'ik people crossed the Bering Strait at least three times: first as Paleo-Eskimos to Alaska, second as predecessors of the Old Bering Sea archaeological culture back to Chukotka, and third to Alaska again as bearers of the Thule culture. During their stay in Chukotka that likely lasted for more than 1000 years, Yup’ik and Inuit ancestors also admixed with local groups related to present-day Chukchi and local peoples from Kamchatka.

Paleo-Eskimo ancestry is particularly widespread today in Na-Dene language speakers, which includes Athabaskan and Tlingit communities from Alaska and northern Canada, the West Coast of the United States, and the southwest United States.

Ancient DNA sheds light on Arctic hunter-gatherer migration to North America around 5,000 years ago (Science Daily)

Greenberg's Hypothesis

A linguistic scholar named Joseph Greenberg (1915-2001) proposed a tripartite division of Native American languages which grouped all languages apart from Na-Dene and Eskimo-Aleut languages into a single language family known as Amerind. He argued that all these languages were derived from a single proto-Amerind language, much as all Indo-European languages derived from a hypothetical proto-Indo European language. Greenberg hypothesized that this meant that America had been colonized by three separate groups of people who corresponded to his three proposed language families.

While highly controversial at the time it was proposed, the genetic evidence has since backed him up. The degree of relatedness to the First American group uncovered by geneticists roughly corresponds the degree of relatedness among the Amerind languages.

[Greenberg's] category of Amerind corresponds almost exactly to the First American category found by genetics. The clusters of population that he predicted to be most closely related based on language were in fact verified by the genetic patterns in populations for which data are available. And the present-day balkanization of Native American languages also reflects a history in which the great majority of populations descend from a single migratory spread.

...Although Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene speakers are genetically distinguishable from other Native Americans because they carry ancestry from distinct streams of migration from Asia, both have large amounts of First American ancestry: around 60 percent mixture proportion in the case of the Eskimo-Aleut speakers we studied, and around a 90 percent proportion in the case of some Na-Dene speakers.

So while Greenberg's three predicted language groups correlate well with three ancient populations, First Americans have made a dominant demographic contribution to all present-day indigenous people in the Americas. (pp. 174-176)

While the separation of the Eskimo-Aleut and Na Dene languages was commonly accepted by linguists, the idea of lumping all remaining American languages into a single supergroup was rejected by many scholars who had classified these languages into as many as 200 separate categories.

However, Greenberg's classification of all African languages into just four major language families—Afro-Asiatic, Niger-Kordofanian, Nilo-Saharan and Khosian—has since become widely accepted since he first proposed it in the 1960s. The question then becomes why Africa—which has by far the longest history of human occupation—has only four macro-language families, while the Americas—which is the continent most recently occupied by humans—has so many. The most likely explanation is that all these languages derive from the original ancestral language spoken by the First Americans who expanded southward during and after the Ice Age.

Population Y

It was recently discovered that some tribes inhabiting the Amazon carry a unique genetic signature most closely related to the current inhabitants of Australasia—the indigenous people of Australia, New Guinea, the Andaman Islands, and parts of the Philippines—than any other Native American groups.

While this genetic signature was most closely related to Australasians, it was different enough to rule out a late migration of Australasians to the Americas as the explanation for this phenomenon. It was also distinct from Polynesians, ruling out a recent migration across the Pacific Ocean to South America as the source of this DNA signature. The signature was strongest in the Tupí, Karitiana, and Xavante populations of the Amazon rain forest, with the largest percentage in the Suruí tribe.

Researchers named this mysterious ghost population "Population Y" after the Tupí word for ancestor: ypykuéra. The signature of Population Y was confined to Amazonia—researchers found no ancestry from Population Y in Mesoamerica or South Americans west of the Andes. Neither was Population Y ancestry found in Clovis burial sites or in Algonquin speakers in North America—it was strictly confined to the Amazon and nowhere else.

It was speculated that Population Y might be related to an earlier group of people that had migrated to the Americas prior to the Clovis culture and who might be the source of the numerous pre-Clovis sites that have been discovered. In this scenario, the remoteness of the Amazon rain forest had preserved a tiny portion of this ancestry which has disappeared from all other native populations in the Americas due to interbreeding with the much larger and more recent Amerind population. This is highly speculative, however, and the ultimate origin of this ghost population is currently one of the most intriguing mysteries in population genetics. However, a 2021 study claimed that this signature was actually a misinterpreted “genetic echo” which represented early East-Eurasian gene flow into Aboriginal Australians and Papuans which has subsequently been lost in modern East Asian populations.

Native Americans, then, derive their ancestry from two major ancestral source populations and three separate migrations to the Americas from East Asia: 1.) The First Americans from Beringia who colonized the continent along the coast from north to south at most 23,000 years ago; and 2.) The Paleo Eskimos who spread the Na-Dene language family into North America beginning around 5,000 years ago, and the Eskimo-Aleut languages and East Asian genes across the Arctic around 1000 years ago (as well as First American genes back into Asia): "Many of these stories have been lost because of the European exploitation that has decimated Native American populations and their culture. Genetics offers the opportunity to rediscover lost stories, and has the potential to promote not just understanding but also healing." (p. 185)

Our 2017 work...revealed a entirely new way to view the deep ancestry of the peoples of the Americas. In this new vision, there were just two ancestral lineages that contributed all Native American ancestry apart from that in Population Y: the First Americans and the population that...founded the Paleo-Eskimos.

We could show this because, we can fit a model to the data in which all Native Americans excluding Amazonians with their Population Y ancestry can be described as mixtures of two ancestral populations related differently to Asians. Mixtures of these two ancestral populations produced the three source populations that migrated from Asia to America and that are associated with Eskimo-Aleut languages, Na-Dene, and all other languages. (p. 184)

NEXT: East Asia