Who We Are And How We Got Here - Part 6 - East Asia

Early farming cultures spread genes and languages throughout East Asia and beyond

DNA studies showed that the split which differentiated West and East Eurasian populations was one of the deepest anywhere in the genetic record.

This split occurred a few thousand years after interbreeding with Neanderthals—around 54,000 to 49,000 years ago, meaning that both East and West Eurasians harbor Neanderthal DNA. East Asians today harbor more Neanderthal DNA on average than Europeans, even though Neanderthals lived geographically closer to West Eurasians. This is because Europeans later mixed with a Near Eastern population that had very little Neanderthal DNA (the Basal Eurasians, whom we met earlier). Basal Eurasian ancestry diluted the amount of Neanderthal DNA present in Europeans.

We found that non-African genomes today are around 1.5 to 2.1 percent Neanderthal in origin, with the higher numbers in East Asians and the lower numbers in Europeans, despite the fact that Europe was the homeland of the Neanderthals. We now know that at least part of the explanation is dilution.

Ancient DNA from Europeans who lived before nine thousand years ago shows that pre-farming Europeans had just as much Neanderthal ancestry as East Asians do today. The reduction in Neanderthal ancestry in present-day Europeans is due to the fact that they harbor some of their ancestry from a group of people who separated from all other non-Africans prior to the mixture with Neanderthals...The spread of farmers with this inheritance diluted the Neanderthal ancestry in Europe, but not in East Asia. (pp. 40-41)

Initial research showed that Europeans shared more mutations with East Asians than they did with native Australians, indicating that the ancestors of Australians diverged from the human family tree sometime before the ancestors of West and East Eurasians split.

It was initially thought that Australians may have derived ancestry from a very early migration out of Africa which took place around 130,000 years ago along a "southern route" prior to the main exodus of human ancestors sometime before 50,000 years ago. This was also implied by the fact that the first Australians used a more primitive stone toolkit than the more sophisticated Upper Paleolithic technology being used elsewhere in Eurasia. These early migrants died out everywhere else, the thinking went, leaving only a subset of their genes in a few populations scattered across Australia and New Guinea.

Later research determined that this result was actually due to a more recent mixture of Australian ancestors and Denisovans around 50,000 years ago. This mixture was exclusive to Australians and, when this admixture was factored in, it showed that the ancestors of Australian aborigines split from the main East Eurasian population sometime after the divergence between East and West Eurasian populations.

The split between West and East Eurasians probably took place sometime before the development of Upper Paleolithic technology, which explains the conspicuous absence of that technology and the more primitive tools used in Australia and other parts of southeast Asia. The presence of this toolkit in more northerly parts of East Asia has been associated with populations that are most closely related to West Eurasians who later migrated east.

My laboratory showed that after accounting for Denisovan mixture, Europeans do not share more mutations with Chinese than with Australians, and so Chinese and Australians derive almost all their ancestry from a homogeneous population whose ancestors separated earlier from the ancestors of Europeans.

This revealed that a series of major population splits in the history of non-Africans occurred in an exceptionally short time span—beginning with the separation of the lineages leading to West Eurasians and East Eurasians, and ending with the split of the ancestors of Australian Aborigines from the ancestors of many mainland East Eurasians.

These population splits all occurred after the time when Neanderthals interbred with the ancestors of non-Africans fifty-four to forty-nine thousand years ago, and before the time when Denisovans and the ancestors of Australians mixed, genetically estimated to be 12 percent more recent than the Neanderthal/modern human admixture, that is, forty-nine to forty-four thousand years ago. (p. 190)

East Asian Ghost Populations

Researchers detected two distinct ghost populations originating in East Asia which contributed to the genetics of East Asian populations living today, both of which are associated with the spread of farming.

They found that today's native inhabitants of southeast Asia and Taiwan derive their ancestry from a homogeneous ancestral population. The Han Chinese, however, also harbor large amounts of ancestry from another deeply divergent population which expresses itself in a gradient running roughly from north to south, with the largest ancestry in the north. This indicated that this second ghost population likely originated somewhere in the northern regions of what is today China.

The researchers speculated that these two ancient ghost populations might have corresponded to the first farmers of East Asia based on their overlap with the archaeological sites where agriculture appears to have first developed.

The population in the southeast would have been the descendants of the the first farmers of the Yangtze River Valley who farmed a number of crops including the earliest cultivation of rice. The northern population, on the other hand, derived from the first farmers of the Yellow River Valley who grew crops such as millet, and later, wheat. For this reason, researchers designated these two populations as the Yangtze River Ghost Population, and the Yellow River Ghost Population.

Our analysis supported a model of population history in which the modern human ancestry of the great majority of mainland East Asians living today derives largely from mixtures—in different proportions—of two lineages that separated very anciently. Members of these two lineages spread in all directions, and their mixture with each other and with some of the populations they encountered transformed the human landscape of East Asia. (p. 194)

These two ancient populations expanded out of their original river valley homelands into the surrounding areas, passing along their DNA in the process. The Yellow River Ghost Population expanded westward into the Tibetan Plateau bringing farming along with them. The expansion of this group is associated with the spread of the Sino-Tibetan language family spoken in China, Tibet, and parts of southeast Asia. Today's Tibetans derive about two-thirds of their ancestry from this population, and about a third from the native hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Tibetan Plateau. The indigenous inhabitants of Tibet appear to have interbred with an extinct species of Denisovans at some point inheriting genes that helped them survive at high altitudes.

One of the most striking genomic discoveries of the past few years is a mutation in a gene that is active in red blood cells and that allows people who live in high-altitude Tibet to thrive in their oxygen-poor environment…the segments of DNA on which this mutation occurs matches much more closely to the Siberian Denisovan genome that to DNA from Neanderthals or present-day Africans. This suggests that some Denisovan relatives in mainland Asia may have harbored an adaptation to high altitude, which the ancestors of Tibetans inherited through Denisovan interbreeding.

Archaeological evidence shows that the first inhabitants of the Tibetan high plateau began living there seasonally after eleven thousand years ago, and that permanent occupation based on agriculture began around thirty-six hundred years ago. (p. 65)

The northern farming population expanded into the Korean peninsula, eventually spreading across the sea to the Japanese archipelago where they mixed with the local hunter-gatherers. The ancestry of the Japanese (Yamato) population today derives from native hunter-gatherer populations who produced the Jōmon culture and a more recent population related to present-day Koreans called the Yayoi people who migrated to Japan bringing rice cultivation with them. This combination is roughly 80 percent farmer and twenty percent hunter-gatherer. The date of mixture was estimated to be around 1600 years ago, which is significantly later than the introduction of rice farming to Japan. This meant that farmers and hunter-gatherers must have kept their distance for a long period of time before intermixing—similar to what happened when farmers encountered hunter-gatherers in other parts of the world.

The Yangtze river valley is generally agreed upon as the epicenter of rice domestication. This ghost population appears to have been the source of the Austroasiatic language family (also known as Mon-Khmer). As they expanded, they spread Austroasiatic languages and rice cultivation to many parts of south and southeast Asia. As we saw earlier, the Austroasiatic languages that are are spoken in India today (such as among the Munda people) are probably due to the migration of the first people who introduced rice farming into India.

However, in many places in southeast Asia, Austroasiatic languages were later supplanted by Austronesian languages, including in Indonesia—today most people in Indonesia speak an Austronesian language. Vietnamese people today are descended from a combination of the Yangtze River ghost population and another deeply divergent East Eurasian lineage. This population also spread to Taiwan around 5000 years ago.

Patrick Wyman connects these populations to the various early Neolithic cultures of China on an episode of Tides of History:

[33:08] ...the middle Neolithic period in China alone was probably responsible for the spread of a number of really important language families. The middle Yangtze and the southward migrants of the Daxi culture may have been responsible the the spread of the Hmong-Mien languages, mostly spoken now by hill people of southern China and southeast Asia; possibly the Kra-Dai languages including the ancestor of modern Thai; and also, if some recent genetic evidence is correct, the Austroasiatic languages, which include Vietnamese and the Khmer language of Cambodia. The Yangshao culture of the Yellow River has been argued to be the the source for the Sino-Tibetan languages, which include the many varieties of modern Chinese and Tibetan.

Neolithic China and Jomon Japan (Tides of History)

Austronesian Languages

Today Austronesian languages are spoken by more than 380 million people from Madagascar to Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the islands of the Pacific as far away as Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Where did this massive language family originate, and how did it become so widespread?

Austronesian languages appear to have originated on the island of Taiwan where rice farming spread from the Asian mainland sometime around five thousand years ago. This population expanded southward to the Philippines around four thousand years ago aided by the invention of advanced sailing technology (including catamarans, outrigger boats, lashed-lug boat building, and the crab claw sail), bringing with them domesticated crops such as taro, breadfruit, bananas, and coconuts; as well as animals including dogs, chickens and pigs. Eventually they reached Near Oceania where they encountered the indigenous peoples of New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago.

Mark Lipson in my laboratory identified a genetic tracer dye for the Austronesian expansion—a type of ancestry that is nearly always present in peoples who today speak Austronesian languages. Lipson found that nearly all people who speak these languages harbor at least part of their ancestry from a population that is more closely related to aboriginal Taiwanese than it is to any mainland East Asian population. This supports the theory of an expansion from the region of Taiwan. (p. 200)

After 3300 years ago Austronesian people associated with the Lapita pottery culture spread outward to western Polynesia including New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa. The Lapita culture is assumed to have arisen during a period of intense exchange between seafaring peoples in East Asia (ultimately originating in mainland China) and the indigenous peoples of New Guinea (Papuans).

After a long pause, the Austronesian peoples resumed their eastward expansion about 1200 years ago to Hawaii, Easter Island, and the least habitable islands of New Zealand; colonizing the most remote islands by around 800 years ago. Austronesians also expanded westward to Indonesia, reaching Madagascar off the east coast of Africa by 1300 years ago. Along the way, they assimilated the earlier Paleolithic Negrito, Orang Asli, and the Australo-Melanesian Papuan populations in the islands at varying levels of admixture.

DNA evidence from burials associated with the Lapita culture from 3000 to 2500 years ago indicated East Asian ancestry but little or no Papuan ancestry; yet today all Pacific Islanders east of New Guinea harbor at last 25 percent Papuan ancestry, with some groups as high as 90 percent.

We succeeded at getting DNA from ancient people associated with the Lapita pottery culture in the Pacific islands of Vanuatu and Tonga who lived from around three thousand to twenty-five hundred years ago. Far from having substantial proportions of Papuan ancestry, we found that they had little or none. This showed that there must have been a later migration from the New Guinea region into the remote Pacific.

The ancestry of the initial Austronesian inhabitants of Vanuatu was largely replaced by Papuan peoples arriving from the Bismarck Archipelago starting around 2400 years ago. Today the current inhabitants of Vanuatu show at least 90 percent Papuan ancestry yet, despite this, the people of Vanuatu appear to have retained the original Austronesian languages. Thus, DNA evidence indicated an exceedingly rare case of language continuity even in the face of almost total population replacement. This replacement did not happen all at once, but incrementally over the course of time suggesting an enduring long-distance relationship between groups in Near and Remote Oceania. The Papuan ancestry currently found in the inhabitants of Vanuatu and other remote Pacific islands comes from different regions of Papua New Guinea indicating at least two separate migrations.

When we...analyzed the Papuan ancestry in Vanuatu, we found that it was more closely related to that in groups currently living in the Bismarck Islands near New Guinea than to groups currently living in the Solomon Islands—despite the fact that the Solomon Islands are directly along the ocean sailing path to Vanuatu.

We also found that the Papuan ancestry present in remote Polynesian islands is not consistent with coming from the same source as that in Vanuatu. Thus there must have been not one, not two, but at least three major migrations into the open Pacific, with the first migration bringing East Asian ancestry and the Lapita pottery culture, and the later migrations bringing at least two different types of Papuan ancestry.

So instead of a simple story, the spread of humans into the open Pacific was highly complex. (pp. 202-203)

It was discovered that the inhabitants of New Guinea carry significant portions of Denisovan DNA in addition to Neanderthal DNA. Around two percent of their ancestry derives from Neanderthals, while 3 to 6 percent comes from a more recent mixture with Desnisovans. In total, five to eight percent of New Guinean ancestry comes from archaric humans—the highest proportion of any existing population.

Patrick Wyman once again connects the spread of Austronesian languages to the early Neolithic cultures of China:

The southward migrants of the Hemudu and its descendant cultures, of which there were several, were probably the source of the Austronesian language family. Today, the Austronesian language family is the most widely distributed language family on earth. It includes languages spoken in Madagascar, Indonesia, the Philippines and Polynesia—as far as Hawaii and Easter Island. Malagasy, Malay, Tagalog, Samoan, and the non-Chinese languages of Taiwan all belong to the Austronesian family.

No descendants of the Austronesian languages survive on the mainland today; they've all been replaced by varieties of Chinese. But if this hypothesis is correct—and it's backed by both genetic and linguistic data—then the lower Yangtze is the ultimate source of this incredibly widespread Austronesian language family.

Transeurasian Languages

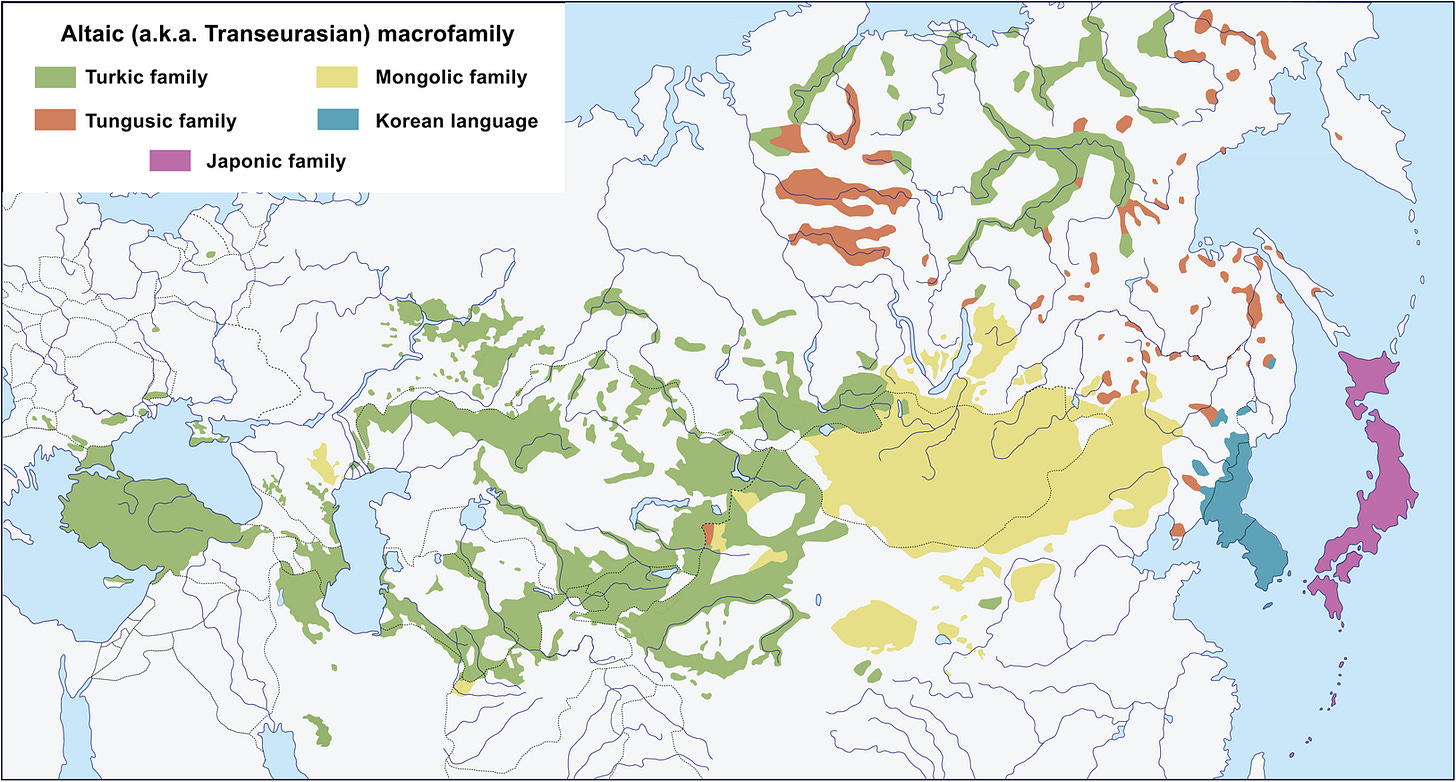

The Transeurasian languages, also known as Altaic languages, include the Turkish languages, Mongolic languages, and Tungusic languages, which are spoken in a vast swath of Eurasia from Turkey to Central Asia through Mongolia, Siberia and Manchuria. Many linguists also believe that Koreanic languages (Korean and Jeju) and Japonic languages (Japanese and the languages of the Ryuku islands) also belong in this family, but this is highly controversial.

However a recent cross-disciplinary study (2020) has provided evidence for the hypothesis that all of these languages are, in fact, related, and their ultimate origin is a Neolithic population that began cultivating broomcorn millet somewhere in the region of the West Liao River around 9000 years ago. This study provided yet more evidence for the "farming hypothesis"—the idea that many of the world’s major language families owe their premodern distribution to the expansion of agricultural populations and the adoption of their languages.

The researchers looked at linguistic, technological, archaeological, and genetic evidence. They found that speakers of Transeurasian languages harbored a distinct genetic signature associated with the Amur region in the far northeast of China which separates modern-day China from the Russian far east. This "tracer dye" was also present in speakers of Koreanic and Japonic languages, adding support for the idea that these languages are ultimately derived from a single source population.

As this population spread out from its ancestral homeland it intermixed with neighboring peoples throughout Central Asia, acquiring a variety of agricultural technologies and splitting off into numerous daughter languages that became the ancestors of today’s Transeurasian languages.

The evidence from linguistic, archeological and genetic sources indicates that the origins of the Transeurasian languages can be traced back to the beginning of millet cultivation and the early Amur gene pool in the region of the West Liao River. During the Late Neolithic, millet farmers with Amur-related genes spread into contiguous regions across Northeast Asia. In the millennia that followed, speakers of the daughter branches of Proto-Transeurasian admixed with Yellow River, western Eurasian and Jomon populations, adding rice agriculture, western Eurasian crops and pastoralist lifeways to the Transeurasian package.

The linguistic evidence used to triangulate came from a new dataset of more than 3,000 cognate sets representing over 250 concepts in nearly 100 Transeurasian languages. From this, researchers were able to construct a phylogenetic tree which shows the roots of the Proto-Transeurasian family reaching back 9,181 years before the present to millet farmers living in the region of the West Liao River. A small core of inherited words related to land cultivation, millets and millet agriculture and other signs of a sedentary lifestyle further support the farming hypothesis…

The new study also reports the first collection of ancient genomes from Korea, the Ryukyu Islands and early cereal farmers in Japan. Combining their results with previously published genomes from East Asia, the team identified a common genetic component called "Amur-like ancestry" among all speakers of Transeurasian languages. They were also able to confirm that the Bronze Age Yayoi period in Japan saw a massive migration from the continent at the same time as the arrival of farming.

Taken together, the study's results show that, although masked by millennia of extensive cultural interaction, Transeurasian languages share a common ancestry and that the early spread of Transeurasian speakers was driven by agriculture.

Interdisciplinary research shows the spread of Transeurasian languages was due to agriculture (Phys.org)

The deep history of Asia shows that cultures which engaged in intensive agricultural production techniques—whether millet farming in the north or rice cultivation in the south—expanded over thousands of years spreading genes, culture and language throughout the eastern end of the Eurasian continent and across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The expansion of the Han people since the Bronze Age, the subsequent conflicts between warring states, and the influx of people from the steppe regions have made the more recent genetic history of East Asia a much more complicated picture for researchers, however.

…right now our understanding of what happened in mainland East Asia remains murky and limited. The extraordinary expansion of the Han over the last two thousand years has added one more level of massive mixing to the already complex population structure that must have been established after thousands of years of agriculture in the region, and after the rise and fall of various Stone Age, Copper Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age groups…it is hard to predict what ancient DNA studies in East Asia will show. While we are beginning to have a relatively good idea of what happened in Europe, Europe does not provide a good road map for what to expect for East Asia because it was peripheral to some of the great economic and technological advances of the last ten thousand years, whereas China was at the center of changes like the local invention of agriculture. (pp. 203-204)

NEXT: In the final chapter in this series, we’ll return to where it all began—Africa.