Inflation: A Guide for Users and Losers - 3

Why inflation came roaring back

So, why did inflation come back with a vengeance after the pandemic?

Blyth and Fraccaroli examine four common arguments for why inflation returned at such high levels after the pandemic, why it persisted, and why it eventually came back down again. They use this as a lens to examine various theories behind why inflation occurs. Some arguments they find compelling, other less so.

1. It was the stimulus checks

This view is particularly common on the internet which is dominated by libertarians. This is often leveled as a criticism of the Biden administration, despite the fact that it was Trump—not Biden—who sent out the first stimulus checks during his first term, the entirety of which seems to have disappeared down the memory hole due to some kind of collective amnesia.

But were the stimulus checks truly the cause of inflation? Blyth and Fraccaroli point out that there are several reasons to be skeptical of this narrative.

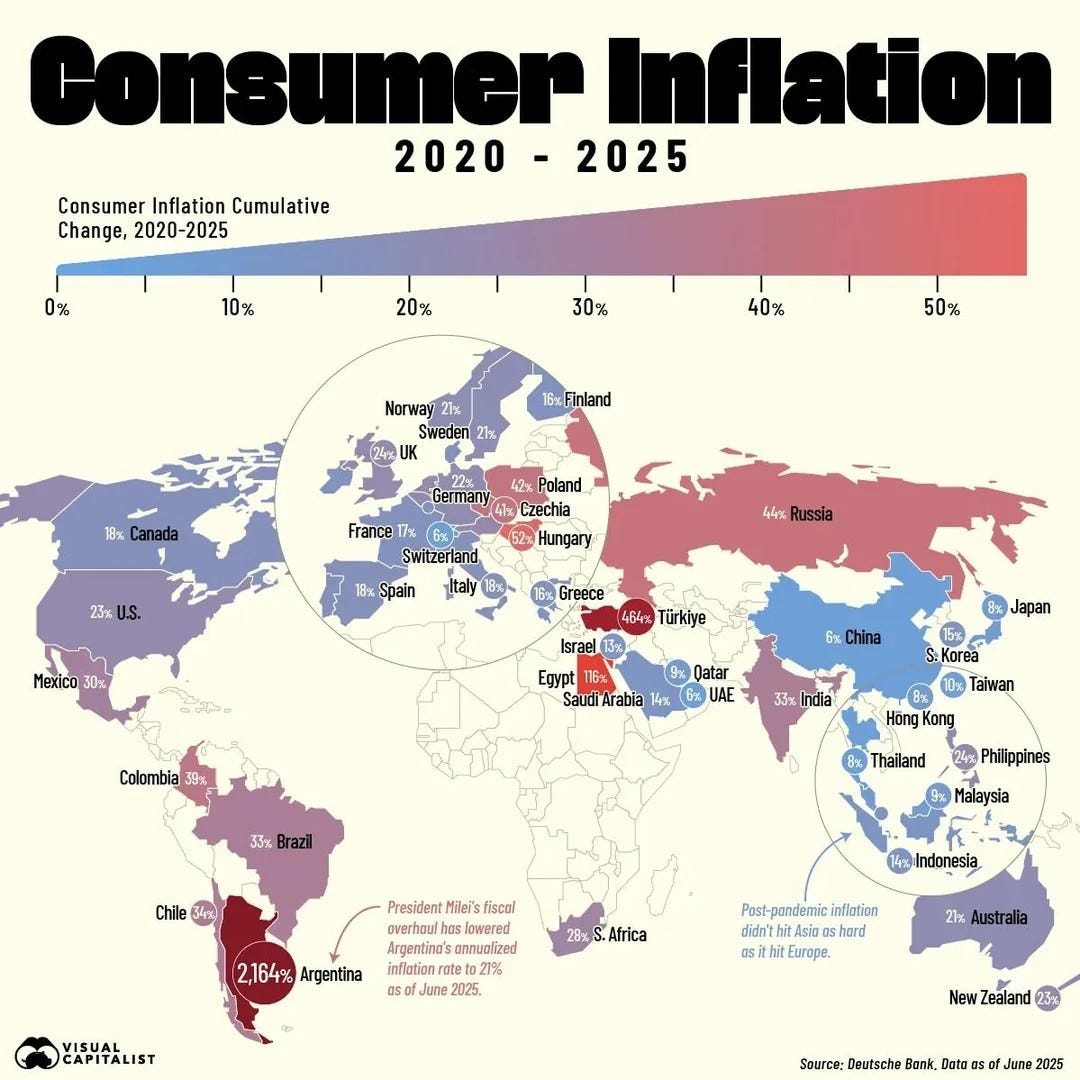

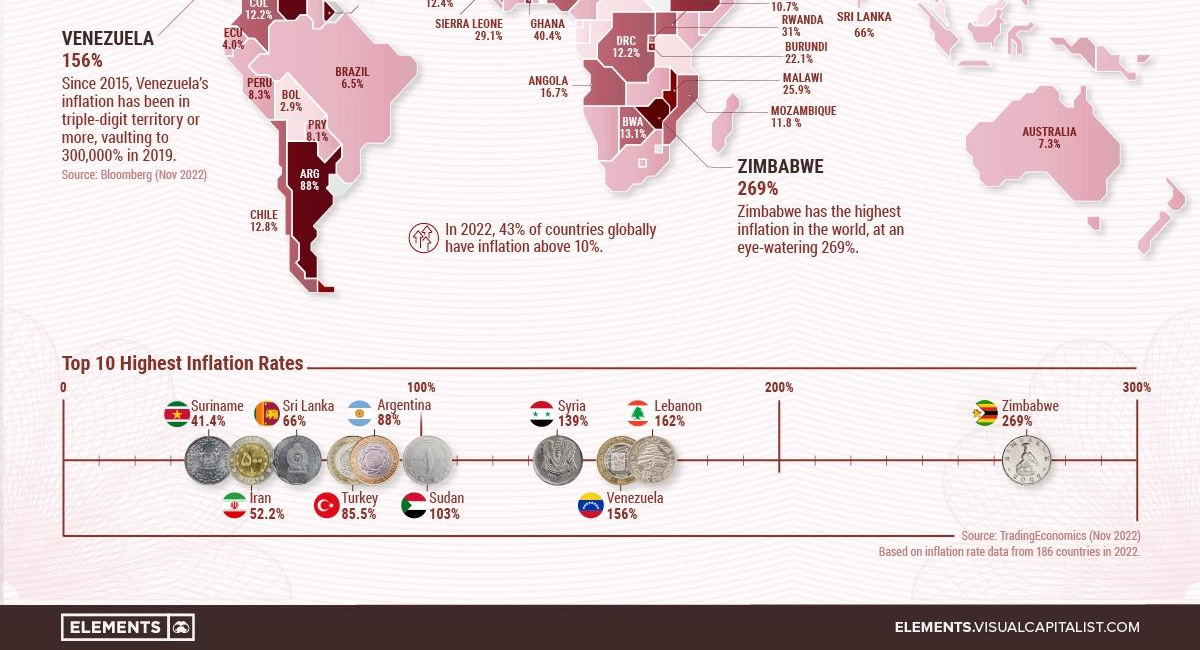

The first, and most obvious, is that inflation was a worldwide phenomenon and was not confined to the United States. Thirty countries around the world experienced high post-pandemic inflation, but only one of those—the United States—received stimulus checks from either Trump or Biden. Thus, it’s hard to blame the stimulus checks for an inflation which affected the entire world.

Second, if government stimulus were the primary cause of inflation, we would expect to see a clear relationship between the amount of stimulus provided by governments to their citizens and the inflation rate. We see no such correlation. In fact, in many cases, it’s the opposite. Countries like Germany, which did less stimulus than the United States, experienced higher rates of post-pandemic inflation, indicating that some other factors must be at play. Inflation in the United States was relatively modest compared to many other countries.

Third, if inflation were caused by the stimulus checks, we would expect it to fade fairly quickly as the checks were either saved or spent. Yet inflation persisted for a long time after the checks were sent out—several years, in fact. It’s hard to reconcile people running out and immediately spending their checks on enough goods to drive up inflation, while at the same time saving their checks in bank accounts that kept inflation elevated for years thereafter. As the authors point out, the checks were simultaneously blamed for both high spending during the pandemic and high savings after the pandemic—a logical contradiction.

If inflation is caused by the stimulus, then we would expect inflation to fade quite quickly as the short-term impact of fiscal expansion dissipates. This would require no specific action as the stimulus in the United States was inherently temporary and time-limited. What went up must come down… (p. 69)

…Finally, the timing doesn’t add up. The checks seem to have been spent in 2022 but also show up as so-called excess savings in late 2023 to explain why consumption in the United States remains robust despite high interest rates. But these are not Schrodinger’s checks. They cannot simultaneously be spent in one period as stimulus and remain unspent in another future period as savings. That simply makes no sense… (p. 71)

It also matters what the checks were spent on. Data on consumer credit from the New York Federal Reserve shows that there was a massive reduction in consumer credit card debt after the checks were sent out. In fact, it was the largest single reduction of credit card debt ever recorded. Based on this, they estimate that 20 percent of the stimulus checks were used to pay down credit cards. There was also a reduction in mortgage delinquencies, indicating that the checks were also being used to pay overdue mortgages. It should be obvious why paying down debt cannot be a driver of inflation. Finally, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics survey in August 2020, sixty-six percent of recipients reported using some portion of their stimulus checks to buy food—hardly a luxury good.

In sum, despite many sensational media stories about the checks being spent on bitcoin and gambling, most Americans seemed to buy financial peace of mind by paying back debt, or buying food, instead of increasing their consumption, all of which is inherently non-stimulatory. (p. 71)

Fourth is the size of the stimulus. While the headline amount seems massive, it pales in comparison to the amount of economic activity lost during the pandemic. For the stimulus to be inflationary, it would have to larger than the trillions of dollars of economic activity which vanished overnight when businesses closed, factories shut down, and nonessential workers were told to stay home.

The authors point out that the handouts given out by the federal government to compensate for lost income—both unemployment benefits and stimulus checks—were less than the income these same workers would have received had they continued to go to work as usual. Much of the stimulus that went directly into workers’ pockets came in the form of unemployment compensation. By definition, unemployment compensation replaces the income lost from not working—it does not supplement it. Moreover, by design, unemployment checks are lower than one’s regular salary, with the expectation that people will “tighten their belts” in the event of job loss and to make sure that not working doesn’t pay more than working. Thus, by definition, this portion of the stimulus could not have caused increased consumer demand—it can only have decreased it.

The remainder of the stimulus came in the form of checks sent out directly to households earning under $150,000 and individuals earning less than $75,000. The authors point out that the total amount of the stimulus checks amounted to only 4 percent of the median household income in the United States, although, of course, it was a higher percentage for those making less than that. Nonetheless, it’s unlikely that this was greater than the income lost by shutting down the entire economy during the pandemic. As we’ve already seen, a big portion apparently went to food and credit card debt, which was probably more likely for those lower down the income scale. While the checks might have kept demand high for items that had vanished from the shelves due to supply chain bottlenecks, they did not in and of themselves cause higher inflation—the supply chain bottlenecks did. We also have no way of knowing how much worse things would have been had the government not tried to stimulate the economy. While inflation may be bad, an economic collapse would be even worse.

…while the headline figure of US spending during the COVID-19 crisis sounds extremely large ($5 trillion or 25 percent of GDP), that needs to be put into perspective. The COVID-19 crisis shut down large parts of the world’s largest economy—especially its service sector which is 80 percent of the economy—for an indefinite period. As such, COVID-19 spending should properly be thought of as compensating for the loss of income and output generated during the shutdown, rather than as a stimulus that was added to an already fully employed economy.

For example, if one examines the bit of the stimulus program that gets the most blame in such analyses, the direct cash transfers component of US spending, you will find that $1.8 trillion of the $5 trillion went to individuals and families. Of that $1.8 trillion, $653 billion went to unemployment benefits, which were in many (but not all) cases, less than the wages they were replacing. As such, unemployment benefits, by definition, could not be stimulatory. Rather, they partially compensated for the spending that usually would have been there.

That leaves $817 billion, which was paid out in three waves of stimulus checks over an eleven-month period that ran from April 2020 to March 2021. Family households with an income of under $150,000 per year and individuals with an income of under $75,000 received three income replacement checks of $1,200, $600, and $1,400 respectively, for a total of $3,200 per household. When we consider that median family income in the United States in 2021 was just under $80,000, these combined stimulus checks added the equivalent of 4 percent to that median income…if those payments were less than the income lost by COVID-19, it’s very hard to see how they could be stimulatory in any strong sense of the word. Surely there were supply constraints, perhaps driven by stimulus-enabled spending, that pushed prices up. But if we imagine a counterfactual where no checks were spent, would we have predicted a mild recession with 80 percent of the economy in lockdown? (pp. 69-70, my emphasis)

A prominent study came out from the Federal Reserve of San Francisco which argued that the stimulus led to prices that were 3 percent higher than they otherwise would be. This was immediately seized upon by the proponents of the “too much money” hypothesis. But Blyth and Fraccaroli point out that the authors of the study themselves note that their estimates are too uncertain to be taken as established fact. In the end, there is no solid evidence that the checks caused inflation with a high degree of certainty.

So the idea that “[Biden’s] stimulus checks” were to blame for inflation doesn’t seem to hold up to scrutiny. This view is peddled by the usual suspects who want to make sure the government never spends any money on average citizens, and only showers money on billionaires and private corporations which is somehow never inflationary.

2. The problem is too much employment

This is basically a variant of the wage-price spiral story from the 1970s based on the Phillips curve logic encountered earlier. The argument is that “greedy” workers are demanding “too much money” from their employers, driving up inflation. The solution, then, as persistently argued by Democratic economic advisor Larry Summers (read that again: Democratic1) was to engineer a recession and create mass unemployment to bring inflation down.

This view is based on the conventional story of what happened in the nineteen-seventies, which we described in part one. It’s no surprise that business and employers love this narrative, because it punishes labor and gives more power to employers.

But, as the authors point out, labor’s back has been broken since the Volcker shock of the 1980s. Workers simply don’t have the bargaining power relative to capital they had back then, and so are unable to push up wages to drive inflation. In fact, real wages were down relative to inflation. They also point out that, for this theory to work, workers must have no “money illusion.”

The “money illusion” is a term economists use for the fact that people look at the salary number on their paycheck or W-2 form and not what those wages are actually able to buy. In economic terms, nominal wages is the number on your paycheck, while real wages are what those paychecks are able to purchase in the economy. So, for example, if you receive a 2 percent raise, you think you’re earning more than before. However, if the inflation rate is 3 percent, you’ve effectively just taken a pay cut. That’s the money illusion2.

But in order for inflation to be caused by rising wages, workers must somehow know what the inflation rate is going to be and bargain for wages even higher than the future inflation rate. But that’s not what people do. They negotiate for an increased number—say 2 percent, or $5000 more per year, without knowing what the inflation rate is going to be over the next year. So how can wages be the driver of inflation?

A very odd but seldom commented upon thing about the Phillips curve story is that for it to work, workers must have no money illusion about wages—they seem to know and bargain for the real wage, which causes the wage-price spiral—but they must have a permanent money illusion about all other prices.

After all, if they knew that all those other price increases were simply nominal adjustments, why would they ever get caught up in that wage-price spiral? Instead, the rational thing to do would be not to adjust to prices going up by asking for more, and, if the Phillips curve logic is right, prices would fall all by themselves. So, for this story to hold water, workers need to be able to bargain for their real wage while being quite schizophrenic regarding prices. That’s really odd when you think about it. (pp. 75-76)

But the biggest refutation is simply that fact that inflation has continued to come down even as unemployment remained at historic lows. In fact, recent research on the Phillips curve has shown it to pretty much nonsense, just like all of Milton Friedman’s other ideas—contrived for political reasons and nothing else.

Research during that lost decade after the financial crisis began to suggest that the modern version of Friedman’s natural rate of unemployment, the so-called NAIRU (the Non-accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment), was actually a statistical chimera insofar as individual countries’ NAURUs jumped around far too much and over too short a period to be considered either “real” or an actual “speed limit” for the economy.

Likewise, research on the Philips curve suggested that it had either vanished or had become horizontal over the prior twenty years as countries seemed to experience wildly different rates of employment with more or less the same very low rates of inflation, independent of their monetary policy stances and central bank constitutions. (p. 157)

3. Inflation is transitory

In this theory, inflation was caused by a series of supply shocks caused by, you know, shutting down the entire global economy! Other supply shocks included crop failures and the war in Ukraine, reminiscent of the alternative view of the 1970s we talked about last time3. According to proponents of this view, once the economy adjusts to the supply shocks, the inflation rate will gradually come back down, regardless of the actions of the central banks. In fact, raising interest rates might make the situation worse, since it makes it harder to invest in additional productive capacity which would ease the shortages.

This was the view adopted by proponents of MMT, for example. While MMT acknowledges that excessive money creation in an overheated economy can be a driver of inflation, it tends to see inflation as resulting from imbalances in supply and demand which can come from either the demand side (caused by, for example, rising wages or tax cuts) or the supply side (not enough supply, for example, due to closed factories, crop failures, or supply chain snarls). It’s important to remember that, as we noted previously, “transitory” is not the same thing as “short-lived.” It simply means that the fundamental factors that are causing inflation must be worked through, and the money supply may not necessarily be one of them.

The authors seem to be amenable to this view, but they point out a flaw in its reasoning. In the conventional explanation, transitory supply shocks do not cause inflation because people expect them to be transitory. As such, they do not bargain for higher wages or run out and buy a bunch of stuff because they expect it to cost more tomorrow. But how do they know whether inflation will be transitory or not?

The argument is that consumers are either smart enough to see the big picture about inflation, or they trust authorities to know how to manage it so they remain unperturbed even in the face of rising prices. But the authors point out a host of studies which show that neither of these things are true. In other words, this theory relies on “expectations” just as much as the conventional explanation for inflation—just in the opposite direction!

Blyth and Fraccaroli are skeptical that “expectations” pay much of a role at all when it comes to inflation, either causing or preventing it.

…it seems that especially in the United States, the economy and employment have both grown while interest rates were increased, and yet expectations remained steady. This…does not accord with the theory that inflation is caused by a de-anchoring of people’s expectations of future price movements… (p. 18)

4. It was greedy corporations

Throughout the pandemic’s aftermath, the mainstream media tried to gaslight us into believing that corporations were not using the pandemic as an excuse to raise their prices. “Corporations have always been greedy!” went the mantra. This was universally endorsed by economists, the business press, the vast right-wing media, and, predictably, by “abundance liberals” like Ezra Klein and Noah Smith, who lectured us that big business and corporations were not the villains, but rather victims just like the rest of us. They pointed to the low profit margins of grocery stores, apparently oblivious to the monopolization of the producers and supply chains which brought those goods to our shelves.

In this view, although “corporations have always been greedy,” what was different this time was that price increases due to the COVID-19 supply shock caused people to lose their benchmark of what a fair price should be, since it was impossible to tell which prices were rising due to genuinely higher costs and which were rising due to opportunistic price-gouging. And since everyone was raising their prices at the same time, there was no real way to tell what items “should” cost, providing cover for those who wished to raise their margins.

Evidence in support of this perspective is quite plentiful but is always contested by mainstream economists. Isabella Weber was one of the first to propose the idea that inflation was driven by profits. In her study with Evan Wasner they showed that in the United States, firms’ profits accounted for 9.4 percent of the increase in inflation (measured with the GDP deflator) since the third quarter of 2020, while wages accounted for only 4.7 percent.

Carsten Jung and Chris Hayes find similar results for Brazil, Germany, South Africa, the UK, and the US. Both studies agree that the concentration of market power among firms acted as an inflation amplifier. By one account, in 2022, the profits of the average US firm increased by 49 percent since the beginning of inflation in 2021. Matt Stoller, research director of the American Economic Liberties Project, analyzed these margin changes in depth and observed something interesting. While corporate profits remained stable from 2012 to 2019, they saw incredible growth in 2020-21. Based on his estimates, increases in corporate profits have cost the average US citizen $2,126.

An even more striking price of evidence is to be found in a survey conducted by Digital.com in November 2021. According to this study, 56 percent of retail businesses acknowledged during earnings calls (when corporate CFOs and CEO get on the phone to their investors before they announce their earnings to the markets) that inflation gave them the ability to raise prices far beyond what they would have needed to offset higher production costs. As a result, on average, firms increased their prices by around 20 percent. As the simple economics story would predict, this was particularly true for larger companies in concentrated markets with automobiles and e-commerce at the top of the list. This is hardly fringe opinion. The European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund’s own research has given us clear evidence that firms’ growing profits fueled inflation in Europe…

According to this view, inflation is higher in the United States than in Europe not because of the higher fiscal stimulus (as the first genre maintains), or because of the peculiarities of the labor market (genre two), or global supply shocks (genre three), but simply because the American economy is more concentrated, and a handful of firms in critical sectors can set prices because they don’t face significant competition and the government does not enforce antitrust laws. Why does this occur? Well, given that those firms are critical funders of those hugely expensive US elections that elect the folks who regulate those firms, one does not have to go far to see a conflict of interest at work here. (pp.87-89, my emphasis)

A 2025 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of St, Louis asked, “What’s Driving the Surge in U.S Corporate Profits?” According to their findings:

Corporate profits have been elevated since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of the last quarter of 2024, they were $4 trillion—2.3 percentage points higher as a fraction of national income than they were prior to the pandemic.

The increase was entirely driven by domestic nonfinancial industries. Notably, retail and wholesale trade, construction, manufacturing and health care experienced a marked increase in profitability. Higher corporate profits mostly went to rewarding shareholders via higher dividends.

What’s Driving the Surge in U.S. Corporate Profits? (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

Why is all of this research and evidence ignored and suppressed by economists and the mainstream corporate media? According to Blyth and Fraccaroli, the reason is because the solutions would be rather inconvenient for the rich and powerful. They prefer the “stimulus” narrative, because it implies that government spending on ordinary citizens causes inflation. They like the “greedy workers” narrative, because it increases the power of capital versus labor. The preferred solution—causing a recession by raising interest rates—increases unemployment which lowers workers’ bargaining power. It also reduces prices for financial assets, which can be bought up on the cheap. Furthermore, it allows banks to raise interest rates, allowing them to make higher profits on loans, and allows the investor class to earn more on their investments like ownership of the national debt (i.e. Treasury bills).

By contrast, if rising prices were caused by corporate price gouging, then raising interest rates will just make inflation worse, because corporations will pass along the increased costs to consumers. The obvious solution in this case would be either price controls or a windfall profits tax. The other obvious solution would be to break up the monopolies and oligopolies that control virtually every sector of the modern US economy.

…as Thomas Philippon has shown for the United States and Brett Christophers has shown for the UK, the “effective” number of firms across many sectors in both countries has fallen significantly, which makes oligopoly pricing more stable and more profitable4. For example, take the US airline sector—battered by COVID-19, hideously indebted, reluctantly bailed out by taxpayers, and loathed by consumers. Its effective number of firms is four. American, Delta, Southwest, and United collectively control 66 percent of the market. In 2023 prices are higher than ever…(p. 87)

In fact, the Biden administration’s robust antitrust enforcement appears to be a major reason why so many in the business community threw their support behind Trump over Kamala Harris. Some of them even admitted this openly. We’ve already seen how many corporations undergoing major mergers have capitulated to Trump’s demands and showered him with what are effectively bribes to grease the merger process.

Bringing it all together then, the evidence indicates that supply shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, failed harvests around the world caused by climate change, and higher energy prices due to the war in Ukraine (especially for Europe), caused prices to spike which acted as a smokescreen for corporations to price-gouge the public, since most of them now operate in highly concentrated markets thanks to several decades of neoliberalism and lax (or nonexistent) antitrust enforcement.

Corporations, politicians, and the media then blamed government spending and deficits for inflation, calling for mass unemployment and a painful recession to bring inflation back down (while still keeping their prices high). Despite a few modest interest rate hikes (which were actually lower than the inflation rate, meaning they were effectively negative), inflation started coming down on its own, at least until the current political regime came to power. This is the “supply-shock plus price-gouging explanation” of inflation, which appears to be the correct one.

5. What about the future?

While inflation has come down significantly in the years since the pandemic, there is evidence that it’s not going away. Blyth and Fraccaroli ponder whether the future is going to offer yet more inflation, or whether we will enter another Great Moderation.

The argument for deflation is that, as noted previously, deflation is the norm for capitalist economies rather than inflation.

Think, for example, of the cost of buying a car over time Imagine a 1979 Volkswagen Golf GTI. Its original price at its UK launch was £4,705, which was $9,536 in 1979 dollars. It was a fabulous car, but it didn’t have airbags, ABS, Bluetooth, navigation, or even air conditioning. The current version of the GTI is superior in every way possible to the 1979 model and costs $29,880. But when you adjust the price of the 1979 model, that is, you price 1979 dollars as 2022 dollars, that translates to $41,370 of purchasing power today. (p. 191)

The other argument is rather more depressing—workers are just too poor and beaten-down nowadays to cause any sort of wage-driven inflation for the foreseeable future. They point out that, in the modern economy, the top-tier corporations make huge profits from ownership of monopoly or quasi-monopoly rights to digital platforms or highly specific intellectual property, but employ relatively few people. Middle-tier companies supply the top-tier companies. But below them, most firms have become franchises that can only make profits by squeezing labor. This limits investment opportunities, because most people and companies have little to spend and are just struggling to get by. As I’ve pointed out before, in the United States, fully half of consumption is now driven by just the top 10 percent of earners, with the bottom half barely registering at all—essentially economic NPCs.

In such a world, inflation can only come from external supply shocks and can only be temporary. There is simply not enough demand in the system to get excited about inflation. (p. 193)

But ultimately, despite this, Blyth and Fraccaroli conclude that the future is going to be inflationary.

The first driver is climate change. The warnings from the world’s climate scientists are becoming increasingly dire, and analysts are starting to take notice. While William Nordhaus famously predicted that climate change effects on the global economy will be minimal because we all work indoors now (seriously!), other analysts are less sanguine. An analysis by the Potsdam Institute found that climate change will raise food prices by 0.92 to 3.23 percent every year, and headline inflation (which includes food prices) will rise between 0.32 and 1.18 percent every year, year after year.

The second driver is geopolitical competition. The globalization that brought prices down and kept them down throughout the Great Moderation is now coming to an end. Simply put, the world is “deglobalizing.” The ability of China to supply an endless cornucopia of cheap goods to the world’s industrial nations has reached its limit. Competition for things like rare earth minerals is going up, causing geopolitical tensions. Every country wants to be a net exporter, but very few want to be net importers, which is obviously impossible. The departure of Britain from the EU shows that countries will voluntarily deglobalize, even at an economic cost to them. The current US administration sees a trade deficit of any sort as being taken advantage of (i.e. a “ripoff”), and is currently engaged in a trade war with the entire world (which happened after the book was published). Free trade is dead.

The third driver is demographics. The world is getting older. The Baby Boomers increased inflation while they were young, but decreased it by 5 percentage points when they entered the workforce from 1975 to 1990 due to their sheer numbers. As they depart the workforce, the cohort replacing them will be smaller, driving inflation up, and this is before any worker shortages that may materialize. The “youth bulge” which added billions of low-wage workers to the global economy from 1981 to 2008 has run its course. Future generations will be much smaller and wealthier, meaning there is less cheap labor to exploit for industrial economies.

Finally, energy prices are going up. The demand for artificial intelligence is already causing electricity prices to skyrocket, while it’s dubious how much economic benefit AI will confer to anyone besides a narrow investor class. The authors do not talk much about fossil fuels (they are economists, after all, not petroleum geologists), but they say it is likely that shortages of fossil fuels will act a bottleneck for economic growth in the future. If some of the more scary predictions of petroleum depletion turn out to be correct (as I’ve suggested), then this will be significant source of inflationary pressure going forward.

All of this suggests to us that inflation may be baked into the DNA of the emergent macroeconomic regime. We may lack a word for it, but we are surely entering a world that is quite different from the world of relatively stable prices we were used to. The green transition—despite how slowly it’s happening and recent backsliding—China’s changing role in the world economy, a new geopolitics of manufacturing, and the aging populations of the Western world (and some Eastern worlds) are all shaping this new macroeconomy…Our hunch is that there is a good chance we are going to see more of inflation in the future, and we hope that this book has provided you with the tools to understand who’s going to win, lose, use, and abuse inflation in that new world. (p. 198)

The money illusion works both ways. People notice rising prices, but ignore rising incomes. For example, in 2024, according to the US Treasury: “We find that in the year ending in the second quarter of 2024, the median American worker could afford the same goods and services as they did in 2019, plus an additional $1,400 to spend or save per year.” But if you point this out, people will get violently angry.

When reporters write articles examining the reasons why the costs of producing something is going up (wine, beer, cheese, milk, eggs, chocolate, tomatoes, beef, coffee, bananas, lumber, sugar, olive oil, and so forth), they find all sorts of reasons like disease outbreaks, bad weather, energy costs, industry consolidation, and labor shortages, but never anything to do with the money supply. We talked about this previously:

Inflation: Secrets and Lies

Lately, I've become quite skeptical of the narrative we're being told about inflation—why it happens, what causes it, why it matters, and what to do about it.

The works cited are Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets, and Brett Christophers, Rentier Capitalism. See also Matt Stoller’s Substack.