“No one in the United States should be retiring at 65 years old. Frankly, I think retirement itself is a stupid idea unless you have a health problem.”

—BEN SHAPIRO

Before we move on, I want to do one final debunking.

No, Social Security is not insolvent. No it is not unsustainable. No, it is not a Ponzi scheme.

If it is eliminated, or reduced, it will be entirely because of political decisions, and not fiscal constraints.

Now, I’m not an expert, or a policy wonk. But what follows is my understanding based on people who know a lot more about this topic than I do. So let’s get started. I’ll try to keep this simple.

1.

If you go on the internet, one of the primary reasons people are so angry about Social Security being potentially withdrawn or curtailed is because “they’ve paid into the system their whole lives,” or something similar. Your hear this all the time from people on Reddit, for example.

Every year when you pay your taxes, there’s a line in your income statement (called a W2 in the United States), showing how much money has been taken out of last year’s paycheck for Social Security.

In this conception, people think of it like a savings account. With a savings account, you sock away a portion of your income every month only to withdraw it at some point in the future. If you stash it in an account that yields interest or dividends, then that money grows over time. It’s your money—the money that you earned in the past. If someone suddenly came along and said you couldn’t access your bank account where you saved all your money, then of course you would be pissed off.

That’s not how Social Security works, however. But the perception that that’s how it works was deliberately encouraged by the system’s architects.

The idea that you’re simply getting your own money back is a “noble lie” that was deliberately sold to an American public hostile to anything remotely resembling “socialism.” The idea of getting “other people’s money”—or (*gasp*) redistribution—would be much harder to sell, they thought. And so they reasoned that people would be more likely to defend the program from attacks if they believed they were simply getting back their own money which they had paid into the system all along.

And, of course, the architects of Social Security were entirely right about that. But it’s still not how the system works.

2.

In reality, that money on your W2 form is paid into a dedicated revenue fund, and that fund pays out all the benefits to the people who are currently receiving checks from the Social Security program.

So, in fact, Social Security recipients are indeed getting “other people’s money.” They’re getting the money that current taxpayers paid in last year, and not the money they themselves paid into the system years ago. That money is “gone”—given to people who received benefits years ago. Taxes paid in 1980 went to 1980 recipients. In turn, your benefits will be paid by future revenues.

Social Security is a federal program that was created under the Social Security Act of 1935. It was established as part of the New Deal by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt with a “dedicated revenue” in the form of a payroll tax. Today, employees and their employers each pay 6.2% of wages up to a taxable maximum of $176,100 (2025) into Social Security.

If you think about it, this makes sense. What about the very first people who received Social Security? Did they pay into the system their whole lives? Of course not! They couldn’t have—it was a new program. And even the people who received benefits for the first few decades of the program’s existence certainly could not possibly have paid in anywhere near what they received in total benefits.

That is, the government does not have to sock away or stockpile money in a savings account like you or I in order to pay for stuff. They just do it.

Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with getting other people’s money. If you’re not living alone on a deserted island, then you’re constantly giving and receiving money all the time from people you’ve never met who also live in that society. If that offends you, then I assume you don’t have any sort of insurance. If you’ve paid into insurance and your house didn’t burn down or you didn’t get into an auto accident, then someone else ended up with “your” money. Did you go to a doctor this year? How many times? Most likely, someone else got some of “your” money this year (with a big chunk also going to health insurance CEOs and stockholders if you’re unlucky enough to live in the United States). Did you pay for 100% of that road you drove on? Ever been to a library?

But this is where the consternation lies. For most of its existence, the amount of money paid into Social Security has been sufficient to cover the number of people withdrawing from it. That means the amount of money the government is collecting (plus what it has saved in the trust fund which we’ll talk about in a bit) is sufficient for what it is required to pay out. This is because, typically, the number of workers outnumbers the number of retirees by a significant margin.

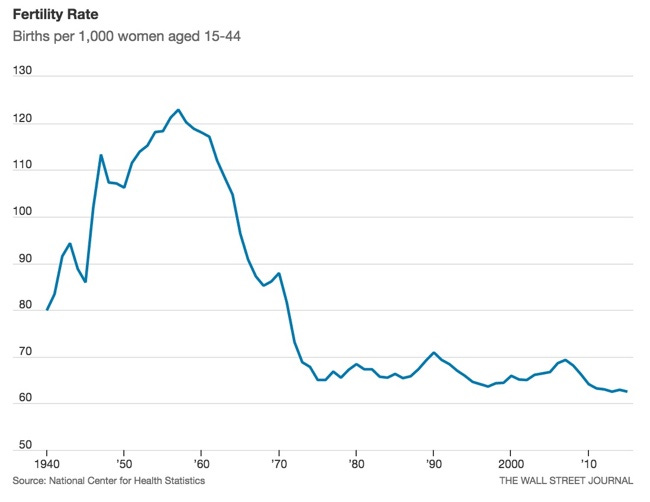

But that margin is rapidly shrinking due to demographics. The ratio of workers to retirees is decreasing. This means that there will eventually be less money coming in relative to what has to be paid out. This is ultimately because of falling birth rates, as the chart above demonstrates.

Which is why there is concern over whether the money will actually “be there” or not. It’s also why detractors sneeringly label it a “Ponzi scheme.”1

3.

It turns out that this demographic cliff was foreseen years ago. You can clearly see the fall off in birth rates in the chart above. By the nineteen-eighties, people were already worried about this, so they decided to do something to guarantee the “solvency” of the program in the future (which, as we’ll see later, is a myth).

Since the massive demographic of Baby Boomers was still working back then, they decided to hike the payroll tax and stash the money away in a so-called “trust fund” to ensure there would be enough money in the future. Sort of like saving up for a rainy day, except the “rainy day” in this case was when the Baby Boomers started to retire. The age at which you could collect benefits was also slowly raised, due to people living longer (a trend which, by the way, has reversed). The money socked away in the trust fund, combined with the revenue from payroll tax withholdings, pays out the benefits that people get every year by law.

The trust fund was supposed to guarantee the program’s “solvency” through at least 2060. However, it is now projected that this trust fund will be exhausted much earlier than anticipated—probably around 2034 or 2035. When the trust fund is exhausted, Social Security will only be authorized to pay out what it collects via payroll taxes, which means a reduction in benefits under the current paradigm.

Is this trust fund “real”? No and yes. It consists entirely of U.S. government debt, which means that it’s just claims by one part of the government on the rest of the government. So you could say that it’s just an accounting fiction. But it has important legal and political implications.

We’ve now reached the point where benefit payments are bigger than revenue from FICA. But for now, the Social Security Administration can maintain payments by drawing on the trust fund, with no immediate need for legislation to bail the system out.

But the reason projections fell short of what was required has to do with something you might not expect: inequality! What the National Commission on Social Security Reform (a.k.a. the Greenspan Commission) failed to anticipate was the astonishing rise in income inequality that has occurred since the Reagan years. What this has meant is that more and more income is not subject to the taxes which fund the program. More on that later.

4.

So is this a problem?

There are a few things to remember here. The first is that the choice to authorize payments from a specific, dedicated revenue source is simply a policy choice rather than a true financial constraint. That is, the payouts are constrained not by a lack of money, but rather by the way the program was initially set up as Stephanie Kelton describes (pay attention to the italics):

1.) Legal Authority to Pay — Under current law, Social Security can only pay full scheduled benefits if there is enough earmarked funding to do so.

Put simply, there must be enough “cash” coming in via payroll tax withholdings or enough “cash” coming in plus “cash” in the Social Security Trust Fund to cover the full cost of paying benefits each year. If the trust funds run dry—i.e. are drawn down to zero—then the program doesn’t have the legal authority (from Congress) to pay full benefits. This would force automatic cuts under current law.

2.) Financial Ability to Pay — As Alan Greenspan explained under oath many years ago, the federal government cannot “run out of money.2”

One does not have to embrace Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to acknowledge that Congress has the financial ability to “create as much money as it wants and pay it to someone,” as Greenspan put it. Social Security is a federal program, authorized to pay benefits to eligible individuals—retirees, their dependents, and the disabled—under the rules established by Congress.

And here’s the most important part (my emphasis):

The reason there is so much anxiety about Social Security “running out of money” is that the authority to pay benefits is constrained by statute. If Congress changed the law to give Social Security permission to pay full scheduled benefits regardless of any earmarked source of funding, then the threat of automatic cuts would disappear…

If we were having an honest debate, we would acknowledge that Social Security can run out of statutory headroom to pay full scheduled benefits, but the money can always be made available. Alas, we’ve become trapped in an eternal tug-of-war over the program’s “solvency,” not unlike two desperate souls fighting over rocks in Dante’s Fourth Circle of Hell.

Everyone just accepts that the program is “running out of money,” so there’s a never-ending battle over the best way to shore up the program’s finances. It’s not the debate I want to have, but it’s the only one that gets any serious consideration…

That is, all it would take would be to pass a simple law stating that the program must pay out the required benefits regardless of how much money happens to be sitting around in some dedicated account somewhere. That’s it. As Warren Mosler put it, “government checks don’t bounce.”

It turns out we already do that for other programs. This Reddit post quotes Kelton’s book, The Deficit Myth, to make the point that all it would take is a policy decision to pay out benefits regardless of what is in a trust fund or any temporary revenue shortfalls.

…the decision to create a Social Security trust fund into which payroll taxes would be paid and from which old-age benefits would be paid out was an entirely political decision on the part of President Franklin D Roosevelt in the 1930s. The trust funds were created to provide citizens with the confidence that funds being deducted from their paychecks for payroll taxes (in an era before the introduction of federal income tax withholding) would eventually be paid out to them in the form of old-age benefits.

As Kelton points out…only three of the four Social Security and Medicare trust funds are subject to these fears that their future "insolvency" might prevent benefits from being paid. One of the two Medicare funds is not subject to these fears. In the legal language governing the Supplementary Medical Insurance fund (SMI)—commonly known as Medicare Parts B and D—“Congress has granted the legal authority to make ... payments” regardless of the cash balance of the trust fund. Kelton writes,

“Congress could in fact change the current law so that the same language applies [to the Social Security trust funds and to Medicare's Hospital Insurance fund]. That it hasn't done so is a political choice, not an economic one. You wouldn't know that by reading most newspapers, however, or by listening to most pundits. All we hear is that Social Security is going broke.” (168-169)

Joe Manchin, Chuck Schumer and Joe Biden all operate on the premises that (a) Social Security and Medicare payments can only be made from the trust funds, (b) those trust funds will eventually run dry, and (c) the purpose of reforms ought to be to push the point at which the trust funds run dry farther into the future. They do not entertain the notion that Congress should simply guarantee payments for Social Security and Medicare Hospital Insurance in the way that it already has for Medicare SMI.

https://www.reddit.com/r/mmt_economics/comments/vwlcak/democrats_approaches_to_social_security_and/

Here’s Kelton herself making the same point:

As the great Northwestern University economist Robert Eisner explained almost a quarter-century ago, Congress could always bestow the same legislative language on Social Security’s trust funds or even dispense with the trust funds altogether. They are, after all, “merely accounting entities.”

Instead of fretting over arbitrary numbers on a ledger, Eisner wanted people to understand that “Social Security faces no crisis now or in the future.” It cannot “go bankrupt.” It will be there as long as those who seek to undermine it don’t get their political way.

So, why not do that? Well, if you wanted to kill off the program, you would certainly not do that. Instead, you would promote myths like it’s “going bankrupt” or that it’s a “Ponzi scheme” which would give you the perfect ammunition to destroy the program, which you wanted to do all along. And the entire media would play along because the media—even the so-called “liberal” media—is owned by billionaires and has always been hostile to anything that helps ordinary workers. You would constantly tell people over and over again that the money “won’t be there” when they retire, and repeat this lie endlessly so that it simply becomes the “conventional wisdom.”

But that doesn’t make it true!

The only other concern would be the amount of real resources the economy is able to generate. As Kelton herself notes, if there is not enough “stuff” (i.e. goods and services) to buy relative to the purchasing power of the checks sent out, then it might make sense to reduce the benefits being paid. The concern is that having so many people out of the labor force might cause economic contraction, resulting in inflation. This is ultimately a question of the size of the entire economy, however, and not a question of whether one specific program has enough money allocated to it. Money can be moved around.

But, as Dean Baker has pointed out, that’s not the narrative we hear in the media. Instead, we’re being told that that future economic growth is going to be supercharged because of AI. If that’s true, then it’s obvious we will have both the real resources and the tax receipts to keep the program solvent while paying out 100 percent of the benefits for the foreseeable future.

The implication…is that AI will lead to a massive uptick in productivity growth. That would be great news from the standpoint of the economic problems that have been featured prominently in public debates in recent years.

Most immediately, soaring productivity would hugely reduce the risks of inflation. Costs would plummet as fewer workers would be needed in large sectors of the economy, which presumably would mean downward pressure on prices as well. (Prices have generally followed costs. Most of the upward redistribution of the last four decades has been within the wage distribution, not from labor to capital.)

A massive surge in productivity would also mean that we don’t have to worry at all about the Social Security “crisis.” The drop in the ratio of workers to retirees would be hugely offset by the increased productivity of each worker. (The impact of recent and projected future productivity growth already swamps the impact of demographics, but a surge in productivity growth would make the impact of demographics laughably trivial.)

What people can’t seem to understand is that it’s not just the number of workers paying into the system, but also the productivity of those workers. If each worker is more productive over time, then incomes are higher, meaning that the amount of revenue is higher, regardless of the ratio of workers to retirees. Workers are a whole lot more productive now than in 1935.

Put another way, if the ratio of workers to retirees falls from 3:1 to 2:1 (as it is projected to do), and future workers are 1.5 times as productive, then the ratio is basically unchanged. This is one reason why Social Security is no more or less a Ponzi scheme than the entire capitalist economy itself3. So, if Social Security is in trouble, so is the entire economy. Its alleged “insolvency” is a choice, not a financial law of nature:

What would an MMT-informed approach to the "problem" of Social Security and Medicare look like?

First, we would have the U.S. recognize that there is no financial problem threatening the viability of Social Security and Medicare payments. As long as the U.S. economy is capable of producing the real resources (goods, services, health care) on which Social Security and Medicare benefits are spent, funding those benefits is not an economic issue. It's only a question of legal authority —and that's a political question.

Second, we would acknowledge that the Social Security and Medicare trust funds have outlived the political purpose for which FDR created them. We would say, "Thank you for your service," and Congress would change the law to guarantee payments regardless of the cash balance level of the trust funds—in effect, politically neutering them.

Third, we would then be able to take up the questions of closing tax loopholes on the rich, making the tax structure more progressive and reducing inequality in the distribution of income on their own merits.

5.

But even if we decided that we wanted to keep the trust fund exactly the way it is now, there’s still another way to ensure that there’s enough money to pay out 100 percent of the benefits for the foreseeable future.

Remember, I said that the reason the trust fund was unable to stockpile as much money as was required is because of extreme income inequality. Perversely, that same income inequality is now being used as an excuse to dismantle the program.

You see, as noted above, the payroll taxes which fund the program top off at $176,100. That means that the most it’s possible to collect from anyone—no matter how rich—is $10,912. That umbrella still covers most workers. But because some people are making so obscenely much more than that in our hourglass-shaped economy, that leaves record amounts of income uncollected by the payroll tax. This is what the Greenspan Commission failed to anticipate.

In 1937, when the payroll tax was first collected, it applied to about 92% of all earned income. By 2020, that figure had fallen to 83%, largely because of an increase in income inequality. Were the payroll tax to be restructured to cover 90% of earnings, as the Congressional Budget Office reported last year, that would produce an additional $670 billion in revenue over 10 years; raise it to cover all annual earnings over $250,000, the gain would be $1.2 trillion — all without cutting benefits by even a penny.

A record share of earnings was not subject to Social Security taxes in 2021 (Economic Policy Institute)

If we were to raise the cap and collect these unpaid taxes from higher-income individuals, then we would raise more than enough money to keep the program solvent basically forever, even without having to pass the legislation described above (note the figures below are a bit out of date):

In 2022, Social Security allocated $1.2 trillion in benefits to Americans. That same year, American gross national income (the total money earned by Americans and their businesses) was just under $26 trillion.

If all of that had been taxed at the standard 6.2%, instead of just $168,600 per earner, Social Security would have accrued $1.6 trillion, a $400 billion surplus. The excess funds could have been saved in the trust funds for deficit years, allocated as benefits, or returned to taxpayers. As eliminating the taxable maximum cap would put social security in a strong financial position despite the current 3:1 worker-to-recipient ratio, we can see how this simple change would secure America’s most coveted program for generations.

But what about those demographics? What about that worker-to-retiree ratio? Doesn’t that mean Social Security is still a “Ponzi scheme” after all? Well, no. As Paul Krugman notes, the best way to think about the way the program is set up is as a dedicated revenue program, which is nothing special in government, nor does it make Social Security a “Ponzi scheme.” For example, if people drive less one year, and less money is collected via gas taxes as a result, and we decide to spend more on road construction than we take in at the same time, that does not mean that road construction is by definition a “Ponzi scheme.” The fact that people come into play is irrelevant—it’s all about the dollars and where they go.

In addition, the problem is self-correcting. People do not live forever. What the chart above shows is a temporary bump leveling off over a long time frame. The Baby Boomers will eventually die off4, and the ratio of workers to retirees will once again come back into a more sustainable balance. We should not let a temporary shortfall allow the usual ghouls to take away one of the meager benefits we still have in this country, one which older generations fought for.

The simplest way to think about government finances — and also, for most purposes, the right way to think about them — is to imagine everything going into or coming out of one big pot of money. Taxes put money in, while government programs take money out…Most revenue goes into a common pot, and most spending comes out of that pot. But some taxes are dedicated to specific programs, which therefore have their own sub-budgets.

A fairly familiar and, I hope, not too controversial example is the Highway Trust Fund. Federal taxes on gasoline and diesel fuel, plus some smaller vehicle-related taxes, are used to pay for spending on highways and mass transit. Why assign certain taxes to certain programs? Basically, it’s about politics. It’s easier to get voters to accept new taxes or tax increases if they’re explicitly connected to paying for something people want…

Which brings us to Social Security, which is supported by FICA — a tax levied on everyone’s wages. People like Musk seem to imagine that workers putting money into Social Security are like, say, small investors buying $Trump coins, whose naivete is the only thing allowing earlier investors to cash out.

But paying payroll taxes isn’t a voluntary individual decision; like paying gas taxes at the pump, it’s the law. And there’s no reason in principle why Social Security couldn’t be run indefinitely on a pay-as-you-go basis, with taxes on current workers paying for retirees’ benefits. In fact, that’s more or less how the system was run until the 1980s. By 1980, however, it was obvious that some adjustments would have to be made. Why? Because the baby boomers were getting older…

In short, the fact that Social Security is funded through a dedicated trust fund is an artificially imposed constraint that its enemies are using to trick us into thinking that the program is unsustainable and that this country can't afford a dignified retirement for all its citizens, even as billionaires get obscenely rich. The elites lie to us because they hate us and want us to suffer. The people who aren’t lying to us are not as well promoted by the media, but I’ve cited some of them here.

So, in conclusion, I hope I have given you the facts to counter the universal narrative that Social Security is “broke,” or that it’s “unsustainable,” or a “Ponzi scheme” or that it “won’t be there” when you retire. It may very well not be, but the reasons have nothing to do with demographics or fiscal necessity. Rather it will be because of political choices that are entirely of our own making. It will be yet another victory for the wealthy and plutocrats in their neverending class war, plunging millions more Americans into poverty and destitution.

The late journalist Kevin Drum summed up the choices we face back in 2011:

If, about ten years from now, we slowly increase payroll taxes by 1.5% of GDP5, Social Security will be able to pay out its current promised benefits for the rest of the century. Conversely, if we keep payroll taxes where they are today, benefits will have to be cut to 75% of their promised level by around 2040 or so. And if we do something in the middle, then taxes will go up, say, 1% of GDP and benefits will drop to about 92% of their promised level. But one way or another, at some level between 75% and 100% of what we’ve promised, Social Security benefits will always be there.

This is not a Ponzi scheme. It’s not unsustainable. The percentage of old people in America isn’t projected to grow forever. Lifespans will not increase to infinity. Taxes go in, benefits go out. It’s simple.

Now, Social Security is not a very generous program, so it’s possible that you won’t want to retire on its modest benefits. But short of some kind of financial apocalypse — in which case we’ve got way bigger things to worry about anyway — Social Security benefits will be there for everyone alive today. Why is it that so few people seem to get this?

Understanding Social Security in One Easy Lesson (Mother Jones)

Amusingly, many of these detractors are actively running cryptocurrency pump-and-dump schemes.

For example, bailing out the big banks and lenders years ago, or the TARP money, much of which was forgiven.

Of course, some people would argue that the entire capitalist economy itself is a Ponzi scheme, but it would be quite a thing to see the libertarian and Republican critics of Social Security accept that argument.

For some people, this can’t come too soon.

As Krugman notes in his column above, the recent Republican tax cuts for the rich amount to 1.2 percent of GDP.