Raiders of the Lost Novel - Part 4

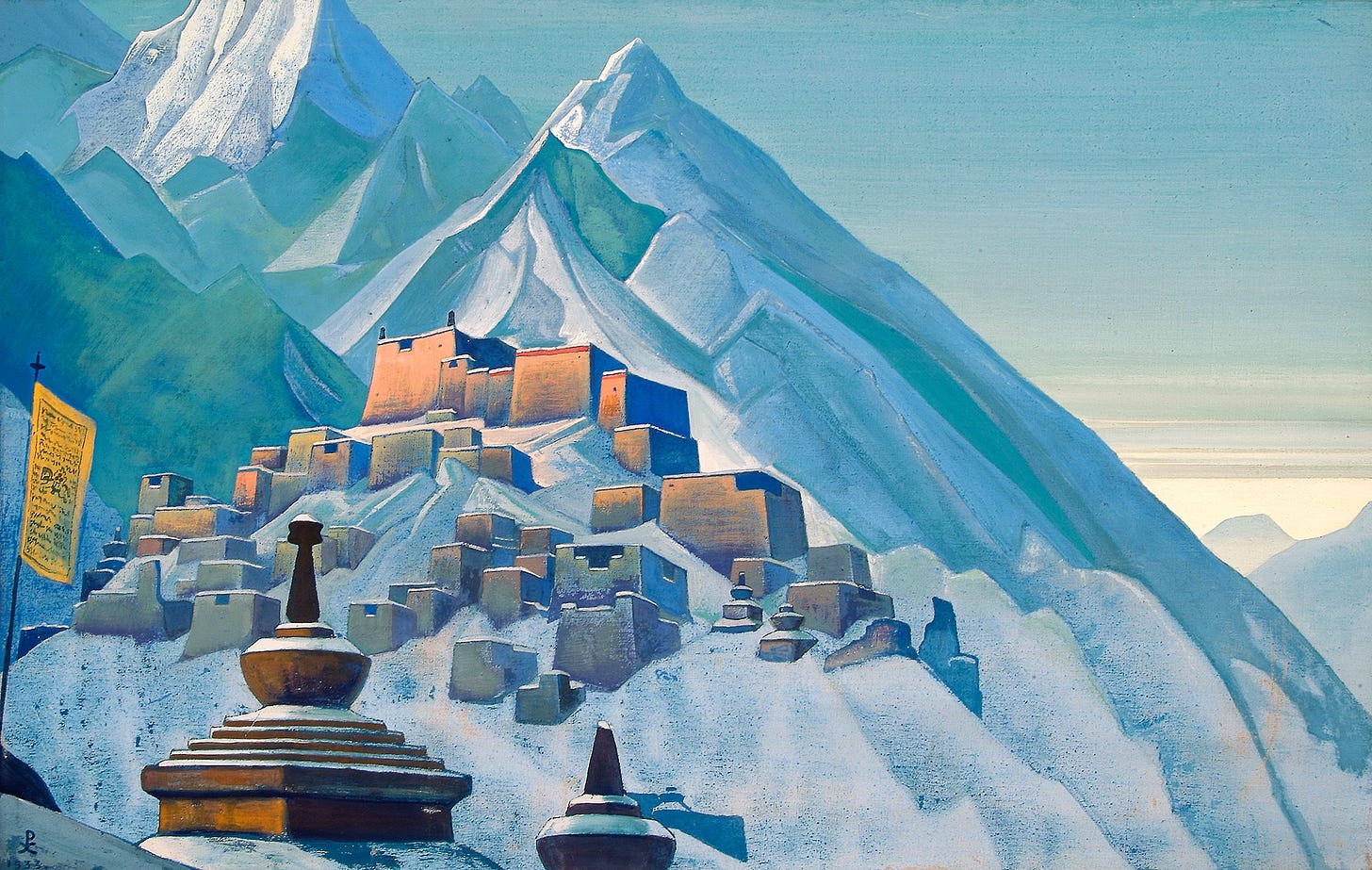

Galahad and the Guru

“Shambhala itself is the Holy Place, where the earthly world links with the higher states of consciousness. In the East they know that there exists two Shambhalas—an earthly one and an invisible one.”

— Nicholas Roerich, The Heart of Asia

The Guru

Nikolai Konstantinovich Roerich (or Rerikh) was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1874. He attributed his love of the Orient to a painting of Kanchen Junga, the sacred Himalayan peak, which hung in the living room of Istara, the summer estate where he spent his youth and which his father had purchased from Count Semyon Vorostov, a diplomat who had traveled through India and named his estate after the Sanskrit word for "Lord" or "Divine Spirit."

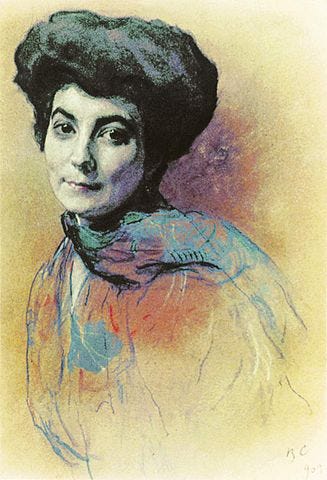

Roerich showed an aptitude for art and enrolled in both Saint Petersburg University and the Imperial Academy of Arts. Although not well known today, in his time he was one of the most famous Russian artists in the world. In Saint Petersburg he met Helena Ivanova, who was also heavily into Theosophy, and they wed. Together they would forge their own particular version of Theosophy which they called Agni Yoga, and the search for Shambhala would be the central focus of the Roerichs’ spiritual quest throughout their life. Throughout the years, they would recruit a large number of followers to their cause.

As the Twentieth Century dawned, pre-revolutionary Russia was a society in ferment. Russia had been shockingly defeated in the Russo-Japanese war, and the tensions that would eventually erupt in the Russian Revolution were on full display. In societies undergoing this kind of wrenching transformation, spiritualism and alternative religions always rise to fore as people seek certainty and solace from what is going on around them, and Russia was no exception.

St. Petersburg was mired in a "crisis of culture and consciousness." The correspondent of Rebus, the Russian Spiritualist journal edited by Madame Blavatsky's sister, reported that the entire capital was caught up "in an unusually powerful and mystical movement" that embraced people at every social level seeking "secret knowledge to fill the aching void."

Gypsy fortune tellers vied with table rappers, hypnotists, phrenologists, and domesticated ghosts at séances in some of the best palaces. Mediums and clairvoyants adorned darkened salons like those of the Montenegrin sisters Militsa and Anastasia ("Stana"), known as Grand Duchess Nicholas and Peter, patrons of the monk Gregor Rasputin. Theosophy became the cult of the intelligentsia... (Tournament of Shadows, p. 449)

Buddhist spiritual ideas became very popular in Russia during this period. The Buriat Buddhist lama Agvan Dorzhiev (mentioned previously) played a major role in this movement. The Roerichs and other Theosophists became interested in Dorzheiv's plans to build a "Theosophical-Buddhist temple" in Saint Petersburg:

Roerich became a determined seeker of Shambhala thanks to Dorzhiev. In 1901, on his way to St. Petersburg, the Buriat had visited Tashilhunpo, where he received from the Ninth Panchen Lama a copy of The Prayer of Shambhala, ascribed to the Third Panchen Lama. This prophecy of the dawn of Shambhala is associated particularly with the Panchen Lamas, who are believed to be the incarnations of the kings of Shambhala. Should the Panchen ever leave Tibet, it would herald, according to the prophecy, the final apocalyptic battle that would usher in the New Age. Warlike conditions will prevail until the barbarians finally attack Shambhala, when they will be destroyed by the King of Shambhala riding on a "stone horse with the power of wind."

The Third Panchen Lama compiled a guidebook, the Shambhala Lanyig, with instructions for reaching the kingdom. Only those persons with exalted spiritual powers would be fit for the journey; only those with heightened awareness would find the way.

The search for Shambhala, which he identified with the Second Coming of Christ and the Maitreya or Buddha to Come, obsessed Roerich. His paintings and writings thereafter conjured up his vision of "a New Age of peace, brotherhood and enlightenment," and his book, Shambhala, published in 1930 after his return from his first Central Asian expedition, was possibly among the sources for James Hilton's Lost Horizon, a best-seller in 1933. (Tournament of Shadows, p. 454)

At this time, Russian cultural exports like art, music and literature were all the rage throughout Western Europe and America. Roerich designed the sets and costumes for the ballet The Rites of Spring, staged by the famous visionary theater director Serge Diaghilev, who founded the Ballet Russes. The production totally blew people's minds and became an international sensation. Roerich's colorful, abstract, quasi-psychedelic sets were particularly singled out, and Roerich would go on to design theater sets and costumes for productions all over Europe and America. Even in those days, the ballet's composer, Igor Stravinsky, remarked that Roerich looked like "either a mystic or a spy." Of course, as we now know, he was both.

When the Russian revolution occurred, the Roerichs fled the country for Finland, and then to London, where they became members of the Theosophical Lodge there. Roerich always publicly identified as a "White Russian" and outwardly rejected Communism, but, as we will see, his true loyalties were more complicated. He received an invitation to exhibit from the Art Institute of Chicago, and it was on the other side of the Atlantic where the Roerichs found a receptive audience for their philosophy.

In New York City, Roerich attracted a number of wealthy backers, including famed pianists Maurice and Sina Lichtmann and the financier Louis P. Horch and his wife Nettie. Like any decent guru, you had to surround yourself with followers—especially ones with high net worth and gullibility—to fund your lifestyle and your adventures. The Roerichs toured America from 1920 to 1923. It was at this time Helena Roerich claimed to be in telepathic contact with an otherworldly being called “Master Morya.” The “Mahatmas,” she told her followers, were in secret communication with the Roerichs, guiding them.

It was Horch who put up most of the money for Roerich's first Central Asian expedition, which lasted from 1923 to 1928. However, unlike the Nazi expedition to Tibet, in this instance seeking out Shambhala was almost certainly one of the goals—if not the primary goal—of the expedition. According to Roerich himself, the mission was both a "scientific expedition" and "a Mission of the Western Buddhists." Nicholas, Helena, and their son George—a Harvard graduate and expert on Asian languages—headed to northern India.

Roerich and company arrived in Darjeeling in 1923. From there they travelled across the border into Sikkim, and from there into central Asia. According to Roerich himself, the expedition "started from Sikkim through Punjab, Kashmir, Ladakh, the Karakoram Mountains, Khotan, Kashgar, Qara Shar, Urumchi, Irtysh, the Altai Mountains, the Oyrot region of Mongolia, the Central Gobi, Kansu, Tsaidam, and Tibet." (Wikipedia) On several occasions they had to fight off bandits with firearms. On the urging of British authorities—especially Colonel F.M. Bailey—they were detained fox six months by Tibetans upon entering the country in October 1927, forcing them to live in tents in sub-zero conditions and draw down their meager rations, which caused the deaths of several people and animals. In March 1928 they were finally permitted to leave Tibet, and they trekked south to settle in India where they founded a research center, the Himalayan Research Institute.

It's too much to go into great detail about their five-year journey here, but there are several incidents which stand out.

One was that Roerich claimed he had been shown the entrance to the subterranean kingdom by an "Old Believer," but it was covered with stones.

Another was the diversion to Moscow. This was apparently done in total secret (Roerich himself always omitted it when discussing the itinerary). This is a source of much speculation and intrigue even today. It's thought that Roerich would not have been able to freely more around Central Asia without the acceptance of Soviet authorities and that he was secretly acting as a spy for the Russians in central Asia and reporting back to Moscow, despite his public opposition to Bolshevism. Roerich, it seemed, was not ideologically committed except to his own prophetic visions, and would work for whomever he needed to to further his goals. In Moscow, Roerich was joined by the Lichtmanns, who were Russian-Jewish emigres, and met with Soviet commissars and other dignitaries including Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Kupskaya, the theater director Konstantin Stanislavky, and (probably) Dorzhiev. Sina Lichtmann recalled a meeting at the GPU (the forerunner of the KGB): “…the names of Maitreya and Shambhala were pronounced…Offers of cooperation were received with enthusiasm.” Roerich would increasingly link Buddhist and Communist ideals in his subsequent writings.

However, one extraordinary fact I learned doing the research for this piece—and which I did not know before—is that the head of the Soviet secret police a this time was himself obsessed with Shambhala! Just when I thought this story could not get any crazier, it gets even crazier. The functionary was named Gleb Bokii, and this is what Wikipedia says about him (although I could not verify the source):

Inspired by Theosophical lore and several visiting Mongol lamas, Bokii along with his writer friend Alexander Barchenko, embarked on a quest for Shambhala, in an attempt to merge Kalachakra-tantra and ideas of Communism in the 1920s. Among other things, in a secret laboratory affiliated with the secret police, Bokii and Barchenko experimented with Buddhist spiritual techniques to try to find a key for engineering perfect communist human beings.

They contemplated a special expedition to Inner Asia to retrieve the wisdom of Shambhala – the project fell through as a result of intrigues within the Soviet intelligence service, as well as rival efforts of the Soviet Foreign Commissariat that sent its own expedition to Tibet in 1924. Bokii also held group sex orgies in his dacha under the pretext of tantric studies.

Gleb Bokii (Wikipedia)

The final—and perhaps most extraordinary incident (which is saying an awful lot at this juncture)—is one of the earliest recorded sightings of a UFO anywhere. So, yes, for you lone Crystal Skull fan out there, we've got you covered. Here's how the incident is described by Roerich in his book about the expedition, Altai-Himalaya:

“On August fifth [1929] - something remarkable! We were in our camp in the Kukunor district not far from the Humboldt Chain. In the morning about half-past nine some of our caravaneers noticed a remarkably big black eagle flying over us. Seven of us began to watch this unusual bird. At this same moment another of our caravaneers remarked, ‘There is something far above the bird’. And he shouted in his astonishment. We all saw, in a direction from north to south, something big and shiny reflecting the sun, like a huge oval moving at great speed. Crossing our camp the thing changed in its direction from south to southwest. And we saw how it disappeared in the intense blue sky. We even had time to take our field glasses and saw quite distinctly an oval form with shiny surface, one side of which was brilliant from the sun.”

In fact, if anything is known about this expedition or Roerich himself to the general public, it is this incident, which you will find crop up in all sort of books and Web pages about the history of UFOs and Ufology. You have to remember that the UFO phenomenon is generally considered to be a post-war phenomenon. The vast majority of UFO sightings (like 99.99 percent) have been since 1947. So a sighting back in 1929 was long before flying saucers or anything like that had entered the public consciousness. According to Roerich, a monk informed them that the sighting meant that their mission had been blessed by the lords of Shambhala. “Did you notice the direction the sphere moved?” the lama asked him. “You must follow that same direction.”

More detail is provided in this excellent essay from Atlas Obscura about the Roerichs and their first expedition: Why the Soviets Sponsored a Doomed Expedition to a Hollow Earth Kingdom. From the article:

What sounds like the plot of a particularly imaginative novel, has been extensively supported by scholars of modern Russia and early 20th century history. According to independent research by Richard Spence, Markus Osterrieder and Andrei Znamenski, several other world governments—China, Mongolia, Japan, Great Britain—took an interest in the hidden city, too. One of the reasons was an ancient Mongolian-Tibetan prophecy which, in the explosive political climate of the early 20th century, sounded convincing enough to turn some heads.

The prophecy declared that as materialism spread, humanity would eventually deteriorate. The people of the earth would be united under an evil king, who would soon attack Shambhala with fearful weapons. In time, the 32nd ruler of Shambhala would triumph over the bad king, and usher in a new era of peace and harmony. What today might sound like a standard doomsday prophecy could have had great implications back then, when borders constantly shifted and even great powers needed the support of local warlords.

The Chinese and Russian governments in particular knew that among the peoples of central Asia, belief in the Kingdom of Shambhala was strong. Whoever managed to identify themselves with the forces of good, would gain the support of the surrounding peoples and thus gain control of the area. Once this was understood, several states became very interested in unearthing the underground kingdom.

Most of the officials intended to use Shambhala’s discovery for propaganda purposes, but some genuinely believed that they could also gain access to the hidden kingdom’s mystical weapons...

The article above focuses on the Soviets, but as we've learned from the previous several posts in this series, Shambhala was also an obsession in Hitler's Germany as well, and might have been an influence on the Nazi mission to Tibet in 1938-1939. But, as we will see in just a bit, it had an impact in the United States as well. The Roerichs returned to America when the trip concluded and Nicholas penned several books, including Heart of Asia, and the aforementioned Altai-Himalaya and Shambhala (which you can read online).

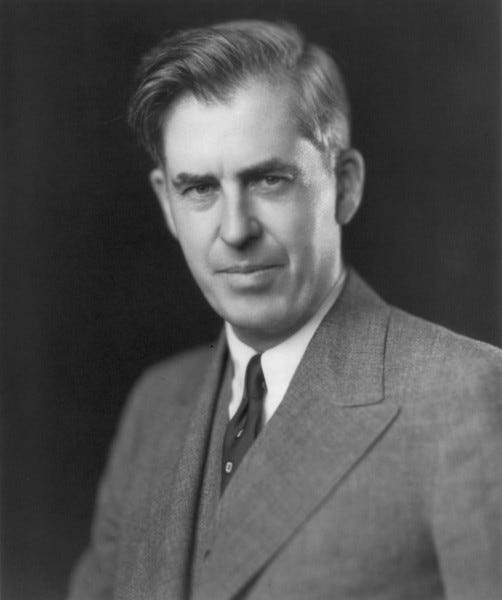

It was in 1929—the year of the Great Crash—when Roerich would meet a man whose fate would become intertwined with his own. That man was Henry A. Wallace.

Enter Galahad

Henry Agard Wallace was born in Iowa, the son of a prominent Iowa farming family1. Wallace’s family published Wallace’s Farmer, and worked on corn breeding. His father, Henry Cantwell Wallace, had served as the Secretary of Agriculture from 1921 to 1924. He had developed a high-yielding strain of corn in his youth, which earned him a great deal of money. Wallace's biography is too extensive to go into much detail here, but for our purposes, it's notable that Wallace was very much a spiritual seeker in his youth, moving between a number of religious movements looking for something more than traditional organized religion could offer. He was raised Episcopalian, but looked into Liberal Catholicism, Buddhism, Judaism, Confucianism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, and Christian Science. That seeking brought him into contact with Theosophy.

Wallace and Roerich first met in 1929. This was a banner year for Roerich. Horch had commissioned the Master Apartments at 103rd Street and Riverside Drive in Manhattan, the bottom floors of which would be a museum dedicated to Roerich's paintings, a school for the fine and performing arts, and an international art center. At this time Roerich was promoting the Roerich Pact, the idea being that items and buildings of great cultural significance would be designated by a special symbol (three balls surrounded by a circle) preventing them from being destroyed by combatants in war. Wallace became very taken with the idea and became it's biggest advocate in Washington2. That same year, Roerich was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize (he would again be nominated in 1932 and 1935).

After the Wall Street crash and the political chaos that followed, Wallace became an avid New Dealer, despite being officially a Republican. In 1932, with the Democrats sweeping into office on the New Deal platform, Wallace was appointed the secretary of agriculture under Franklin D. Roosevelt—the same office his father had previously occupied. While in office, Wallace became interested in breeding crops which could resist the dry conditions of the Dust Bowl. He thought that the hardy drought-resistant grasses which grew on the plateaus of Inner Mongolia, Tibet and Manchuria might provide an answer. To that end, he authorized an expedition to Asia under the aegis of the Department of Agriculture, dispatching two Department botanists to collect samples and bring them back to the United States. But to lead the expedition, Wallace insisted on Nicholas Roerich over the objections of, well, pretty much everybody including the State Department. Remarkably, Roerich's Russian background and his potential work as a spy for the Soviet Union were either missed or overlooked.

The expedition was a calamity. Roerich and his son George made off for Japan, and then for Manchuria, well in advance of the botanists. In Manchuria, he committed a major diplomatic faux pas by appearing to recognize the Manchukuo puppet regime, which the United States had not officially recognized. In fact, the biologists saw little of Roerich, who appeared to be following his own directives which were quite different from the goals of the mission. The expedition effectively split into two separate missions, with the biologists collecting plant samples while the Roerichs visited monasteries, copied medical texts, and discussed the coming "War of Shambhala" with lamas. The scientists notified Wallace of Roerich's erratic behavior, but Wallace sided with Roerich and threatened to dismiss them.

It appeared that Roerich was intent on carrying out "The Plan," which he and some of his followers had developed years earlier. The Plan basically consisted of bringing about an earthly Shambhala: the establishment of an independent, pan-Buddhist cooperative located somewhere in north-central Asia under the leadership of the Panchen Lama. In this endeavor, he had hoped to ally with Japan, the most powerful Buddhist country in the region, and began to stockpile weapons and recruit followers to carry out the task alarming both Britain and Russia. According to the book Henry Wallace: His Search for a New World Order, Wallace was apparently aware of “The Plan” and had attempted to convince American billionaires "of a mystical bent" to help fund it. Roerich's subversive activities were the subject of sensationalist press articles, alarming powers in the region, especially Russia. Eventually, the fallout from the Roerichs’ “bull in a china shop” approach to diplomacy and unsanctioned activities became too embarrassing for Wallace to ignore any longer:

What finally caught Wallace's attention was a telegram from Moscow, dated August 20, 1935, from William Bullitt, the American Ambassador. Bullitt's military attache, it appeared, was informed by a Soviet source that the Roerichs and the White Russian recruits were roaming Mongolia. The cable concluded: "The armed party is now making its way toward the Soviet Union ostensibly as a scientific expedition but actually to rally former White Elements and discontented Mongols." (TOS, p 488)

Wallace recalled the mission, apologized to the scientists, and cut off all ties with the Roerichs, but the damage was done. No longer under U.S. protection, the IRS brought a suit against the Roerichs for failure to file tax returns, joined by lawsuits from Horch who by this time had fallen out with the guru. Sensing the heat, the Roerichs settled in India permanently, never setting foot in the United States again.

“Dear Guru”

By 1940, Roosevelt had already served two terms. He decided to break with the informal tradition established by George Washington and seek an unprecedented third term as president, on the idea that the work of the New Deal was not complete and the country needed the stability that his administration provided. Roosevelt had never really seen eye-to-eye with his vice president, John Nance "Cactus Jack" Garner, who had been picked by others. Instead, he chose Henry A. Wallace to be his running mate in 1940. This was greeted with much consternation in Democratic political circles, but Roosevelt stood firm, threatening to leave the ticket if Wallace were replaced.

It was during the 1940 campaign when the correspondence between Henry Wallace and Nicholas Roerich first came to light. It's unclear from the accounts I read where the letters originally came from or how they were exposed, but they somehow fell into the hands of the Republicans who threatened to use them against the campaign. There was even talk of removing Wallace from the ticket. But Roosevelt had an ace up his sleeve. His campaign had found out that the Republican nominee, Wendell Willkie, had had an affair with Irita Van Doren, the literary editor of The New York Herald Tribune. The Roosevelt campaign threatened to reveal this to the press, and in a case of potential mutually assured destruction, the letters were never released (American politics has always been this way)3. Roosevelt went on to win a third term in 1940. At the end of 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, ushering the United States into World War Two.

In 1944, as the war raged on, Roosevelt decided to seek a fourth term. By this time, his health was already failing. An internal revolt was staged inside the Democratic Party, led by segregationist Southern Democrats who had always opposed Wallace for his principled opposition to segregation and his generally progressive stances on economic and social issues. The revolt was successful, and they replaced Wallace with the much more conservative, compromise-friendly senator from Missouri, Harry S. Truman, despite 64 percent of the delegates preferring Wallace and just 2 percent favoring Truman. This time Roosevelt could do nothing and acquiesced. Roosevelt once again won the election, with Harry Truman as his vice president. Wallace was made head of the Department of Commerce as a consolation. Roosevelt died in 1945, making Truman the 33rd president of the United States, a position which, had it not been for the vagaries of fate, Wallace would have occupied.

After the end of the War, sparks flew between Truman and Wallace over foreign policy. Wallace wanted to adopt a more conciliatory approach towards the Soviet Union to avoid what would eventually become known as the Cold War. Instead, Truman's more hawkish stance prevailed, and Truman fired Wallace. Wallace would be pilloried for the rest of his career as being "soft on Communism." The video below goes into more detail about this whole time period and what happened:

In 1948, Wallace ran as a third-party presidential candidate on the Progressive Party ticket. This time, however, there was no one to protect him from the letters. They fell into the hands of a character called Westbook Pegler—a so-called "conservative populist" and the spiritual godfather to modern-day scumbags like Tucker Carlson, Sean Hannity, et. al. (we've always been awful). They were dubbed the "Dear Guru" letters, and Pegler gleefully released them to destroy Wallace's reputation and make him look like a crank. The letters were full of odd mystical references which would have certainly seemed bizarre to anyone reading them at the time. Wallace referred to himself as 'G' for Galahad—the code name Roerich had given him. Here's a sample:

"I find the W. One [Wavering One, a code name for President Roosevelt] has a very pronounced attitude toward the Rulers as you might guess from the S. One [Sour One, a code for Secretary of State Cordell Hull]...He thinks the Monkeys [Great Britain] will be against the Rulers [Japan] two years hence. These are very busy days and openings do not appear...Have you heard from the horoscope? Its analysis will confirm certain of your ideas." (TOS, p. 475)

Wallace refused to confirm or deny the letters and dismissed anyone who brought them up as a "Pegler stooge." In a dramatic incident, the doyen of American journalism at the time, H.L. Mencken (who referred to Wallace as the "Swami"), raised the issue at a press conference. Mencken was above reproach, and yet Wallace still demurred and refused to give a straight answer. This permanently tarnished his reputation and sank his campaign. As the famous journalist later remarked, "Wallace’s imbecile handling of the Guru matter revealed a stupidity that is hard to fathom. He might have got rid of it once and for all by simply answering yes or no, for no one really cares what foolishness he fell for ten or twelve years ago." (TOS p. 477)

It's difficult to blame the Dear Guru letters for Wallace's loss, considering he was running as a long-shot third party candidate (as was racist Democrat Strom Thurmond). It was commonly believed that these candidates would split the Left vote, handing the election to the Republicans (yes, for my fellow Americans, nothing ever changes in this country). This is the origin of the famous headline, "Dewey Defeats Truman." Wallace's million-plus votes did cost Truman the electoral votes of New York, Michigan and Maryland, and a swing of only 30,000 votes could have cost him California, Ohio and Illinois. Instead, Truman eked out a slim victory and became the nation's next president and successor to Franklin Roosevelt.

The Dear Guru letters is such a bizarre incident, and yet it's hardly known today. It's hard to believe that everything I've written above is 100 percent true. Wallace comes off as a compelling character. With his tousled hair and boyish good looks, he looks perfectly suited to appear in a movie looking more like Jimmy Stewart than Jimmy Stewart himself. His views were ahead of his time. Was he a true believer in Shambhala? Did he believe the legends, or did he just want to help bring about a Central Asian cooperative that would help usher in a more peaceful "New World Order?"

If Wallace had become president instead of Truman, it's hard to know how profoundly history would have changed. Coincidentally, another film out right now—Oppenheimer—plays into this story. Would Wallace have dropped the bomb? Some scholars and historians think not. And Wallace's foreign policy views would have certainly caused the Cold War to unfold very differently than it did, with nuclear annihilation once again hovering over humanity. Maybe Wallace would have even pushed for Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights, which has since been abandoned as “pie-in-the-sky” and “unrealistic.”

Incidentally, one of the things Wallace is still occasionally known for is his essay, "American Fascism," which is sadly once again disturbingly, achingly relevant:

“The really dangerous American fascist... is the man who wants to do in the United States in an American way what Hitler did in Germany in a Prussian way. The American fascist would prefer not to use violence. His method is to poison the channels of public information. With a fascist the problem is never how best to present the truth to the public but how best to use the news to deceive the public into giving the fascist and his group more money or more power... They claim to be super-patriots, but they would destroy every liberty guaranteed by the Constitution. They demand free enterprise, but are the spokesmen for monopoly and vested interest. Their final objective, toward which all their deceit is directed, is to capture political power so that, using the power of the state and the power of the market simultaneously, they may keep the common man in eternal subjection.”

— Henry A. Wallace, former vice president, in 1944

Enter the OSS

The 1942-1943 American expedition to Tibet took place during Wallace's tenure as vice president, but I could find no direct connection between Wallace and the expedition itself. Instead, the mission was undertaken by the newly-created Office of Strategic Services, or O.S.S., an organization which is considered to be the precursor of the C.I.A. Fans will also note that this is the organization that Indiana Jones worked for during World War Two which, if you know anything about their exploits, makes perfect sense. The O.S.S. was under the direction of Colonel William "Wild Bill" Donovan.

The expedition's leader would be a man by the name of Ilya Tolstoy. That surname is no coincidence—Tolstoy was indeed related to Count Leo Tolstoy, the great Russian novelist (and Christian spiritualist writer). His remarkable biography is hard to believe.

Ilya Tolstoy was born on the Tolstoy estate in Yasnya Polanya in 1903, the son of Andrei Lvovich Tolstoy, the ninth of Leo and Sofia’s thirteen children. He was schooled in England (where he corresponded with Jack London and Ernest Seton Thompson, among others) while his father served in the Russo-Japanese War. In 1916-1917 he was a cavalry officer in Turkestan for the White Russian Army. After the war, he bred horses at the Tolstoy estate, traveling all over Turkestan and Siberia to find specimens. In 1921-1922, he volunteered with the American Friends Service Committee during the famine in the Volga district. With Quaker help, he entered the United States in 1924 on a student visa, enrolling at Iowa State College where he studied genetics and animal husbandry, working summers as a farmhand.

He became a protegee of William Douglas Burden, a trustee of the American Museum of Natural History. With Burden’s backing, Tolstoy became a documentary filmmaker, traveling all over the world, including leading an expedition to northwest Canada and the Arctic to film the migration of caribou (released by Paramount as the documentary Silent Enemy). He eventually settled in Florida where he became the founder and general manager of Marine Studios, Marineland, near St. Augustine.

Tolstoy would select a single companion on the journey because, in his words, "The mission I felt, would have a better chance of success if shared by two men. If one was lost, the other might get through." The man he chose for this task was Brooke Dolan, and it here where we finally get to meet our Indiana Jones.

Brooke A. Dolan II was the son of a Philadelphia utility magnate and had grown up in the lap of luxury. Yet, despite this, he inwardly burned with an intense desire to escape the repressiveness of civilization and polite society and live in the wild for much of his adult life.

As a youth in his twenties, Dolan had dropped out of Princeton to lead two expeditions through Central Asia and China to seek out specimens for Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, of which he was a trustee. But he wasn't alone. On both expeditions, he was accompanied by a promising young scientist whom he had met in Hanover, Germany.

That scientist’s name? Ernst Schäfer.

Yes, Dolan and Schäfer were not strangers; at one point they had been very good friends. But on their previous expedition they had had a falling out—one for which Schäfer would carry a grudge for the rest of his life. Nonetheless, Dolan donated money to Schäfer's Tibet mission, contributing four thousand dollars.

Next time: Dolan and Schäfer’s adventures in the Far East.

Ironically, near the town of Orient.

Wallace was also responsible, allegedly under the influence of Roerich, for putting the pyramid with the all-seeing eye and the phrase "Novus Ordo Seclorum" on the dollar bill, launching a thousand conspiracy theories.

Technically, they were published by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (along with a response by Wallace), but since the Republicans made nothing of it, the story quickly vanished.

What a pleasure to read that sort of stuff.

Fantastic stuff!!