“The whole life of the upper classes is a constant inconsistency. The more delicate a man's conscience is, the more painful this contradiction is to him.”

—LEO TOLSTOY

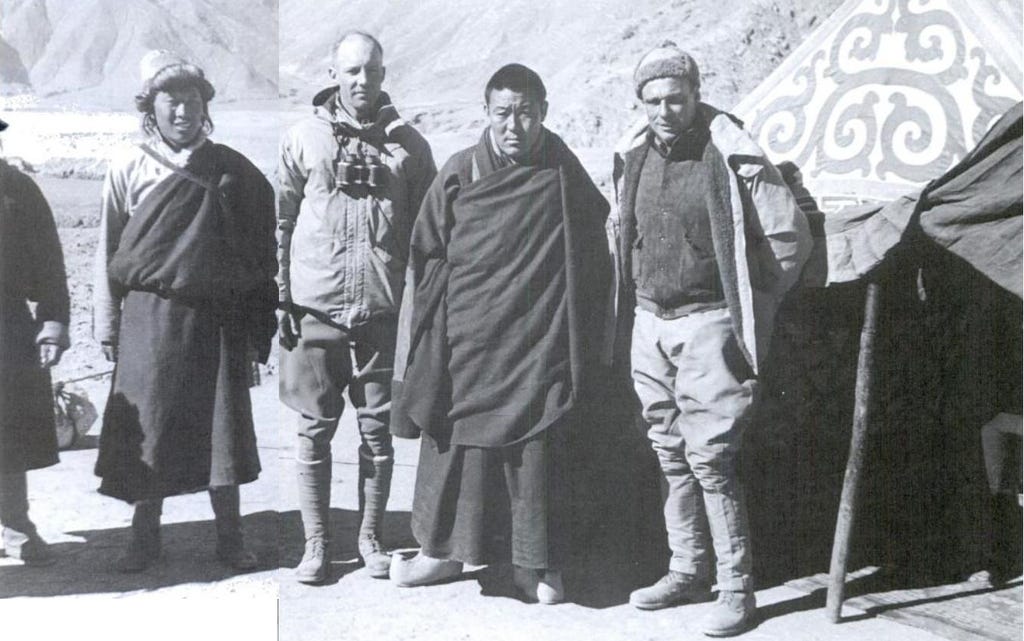

Tostoy first met Brooke Dolan in 1942 in the War Room of the Army Air Force Chief of Staff. Dolan had signed up for the Army immediately after Peal Harbor and was chafing as a deskbound presentation officer in Washington DC. He was “casting an eager eye around for overseas duty,” according to Tolstoy, and would get his chance when “Bill” showed up and chose him to be his companion on the mission to Tibet.

In the spring of 1942, Japanese armies were storming through Asia and had shut down the Burma Road, the main supply line to Chinese Nationalist forces battling the Japanese. Alternate supply routes were needed, and going through Tibet seemed like a logical option. Supplies could be airlifted, but the route over the Himalayas—known as "The Hump"—was fraught due to its thin air, high winds, and wild, unpredictable weather. Many transports were lost, and an overland route was proposed as an alternative1.

We've already covered some of Dolan's personal struggles, including his antipathy towards civilization, his difficulty fitting in to polite society, and his battle with alcoholism. Tolstoy had his own issues, including a wife and children who were trapped inside Russia as he noted in the biographical sketch he prepared for the OSS: “At what must have been immense psychic cost, Tolstoy kept his silence in the Himalaya, saying little or nothing about his Russian family even as German armies trampled through Russia, in a nightmarish reprise of War and Peace.” (TOS: 534)

Ilya Tolstoy and Brooke Dolan were a good match for a risky and exacting assignment. Both were proficient on horseback and with a rifle. They had traveled widely in Asia, spoke many of its languages, and knew the importance of patience and fair-dealing with guides and porters. They were in their prime: Tolstoy was thirty-nine, Dolan thirty-three...Yet their tempers were very different. Beneath a surface affability, Tolstoy was tautly controlled, a former cavalry officer whose affinity was with horses. Dolan was impulsive, self-punishing, liable to outbursts of violence; his affection was for dogs. Both men bore the intangible baggage of troubled marriages and traumatic pasts. (TOS: 532-533)

Initially they planned to proceed to Lhasa from Chungking in Szechuan, but the Tibetans categorically rejected any entry from China. Instead, the expedition would travel almost the exact same route taken by the Nazis years earlier, through Sikkim via the Natu La Pass to Gyantse. Officially, the expedition was to “move across Tibet and make it's way to Chungking, China, observing attitudes of the people of Tibet; to seek out allies and discover enemies; locate strategic targets and survey the territory as a possible field for future activity.” (TOS: 541) No word on any search for Shambhala.

Lhasa Lo!

Tolstoy and Dolan flew to New Delhi in September 1942, sleeping on the hundreds of pounds of equipment and gifts for Tibetan officials which had been crammed into their plane. Since entry into Tibet was forbidden, British officials worked behind the scenes to secure the pair entry via wireless communications with Lhasa. At this time New Delhi was struck by rioting in the streets and the city was declared out of bounds. After the rioting subsided, they were requisitioned a jeep and allowed to gather supplies. Before departing New Delhi, they were personally contacted by General Joseph "Vinegar Joe" Stillwell, who wished them Godspeed (in his perfect Chinese, Tolstoy adds). From New Delhi they loaded their equipment onto the train for Calcutta. Their cabins were so crammed with boxes and equipment that they had to sit on their cases. They arrived safely in Calcutta, although the train immediately behind them was derailed by rebels.

From Calcutta they took the night train to Siliguri. There they were met by Sandup, a 29-year-old Tibetan telephone & telegraph operator who would be their interpreter. They loaded their crates of equipment into aging touring Fords and drove to Gangtok over narrow, winding mountain roads precariously perched hundreds of feet above canyon streams below. The roads were constantly being repaired by gangs of Gurkha and Lepcha laborers (who, Tolstoy notes, were mostly women.) The roads were so narrow that at one point they had to get out of their cars and proceed single file.

They arrived in Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim, and stayed at the country house of Sir Basil John Gould, the same British official who had dealt with Schäfer and the Nazis years earlier (whom they dubbed “BJ”). In Gangtok they added a couple of additional members: a half-Chinese, half-Tibetan cook called Thami—which immediately became “Tommy”—and Lakhpa, “a quiet, hardworking Lepcha about 26 years old.” At the time, Gould was hosting the Prime Minister of Bhutan and his Tibetan wife and was working on a Tibetan dictionary. They received permission to proceed as far as Lhasa, but no further.

They departed for Tibet on a clear day in October. Along the way they stayed in dak bungalows—government rest houses—each spaced about a day apart. The bungalows were warmed by burning yak chips, filling them with acrid smoke. They traveled slowly given the 14,000 foot altitude, which forced them to sleep sitting up.

Crossing the Natu La pass, they arrived at Yatung in the valley of Amo-Chu where they were “called upon by all the dignitaries of the city.” Yatung was one of the larger cities of Tibet, despite having only a couple thousand inhabitants. They spent several days there meeting with various officials and dignitaries, including the merchant Pangda Tsang, “one of the two strong men in the Tibetan world of finance. He is a Yatung merchant, whose agency is scattered far and wide...”

Tolstoy and Dolan quickly mastered the complicated rules of Tibetan etiquette—for example, the more important the caller, the farther away from the room they had to meet them; and sticking out one’s tongue and making a hissing sound as a sign of respect. Greetings and farewells were accompanied by the exchange of white scarves—“like leis in Hawaii” is how Tolstoy puts it. The government officials expressed surprise at the humbleness of the entourage for such a great power: “Our three assistants and few pack animals made a show so unimpressive that we had to resort to the excuse that in wartime everything must be done simply and economically.”

While in Yatung they received the “Red Arrow Letter,” a large cloth parchment containing instructions from the Dalai Lama stating that two American officials were traveling to meet His Holiness and requesting that the headmen of local villages provide them with accommodations and transport.

They were given the customary military send-off from Yatung and proceeded to Phari Dzong, several days' journey away. Farmers in the fields were making hay, their donkeys piled high with straw. The saddlelike, open territory was freezing but also arid, since the Himalayas caught the moisture coming from the south. The passes were adorned with sacred mani stone pillars and prayer flags. Tibetans believed that a mani stone left near a monastery would continue the prayer after the pilgrim had left. In Phari Dzong they stayed in a house which doubled as the world's highest post office. On October 22 they crossed the Tang La Pass at 15,200 feet into the vast Tibetan plains.

Passing through the Tromo valley with its villages of stone houses with shingled roofs, they saw farmers growing barley and peas while cattle herders and nomads came down into the villages to trade. “Magnificent specimens of manhood, they were clothed only in sheepskin chupas (capelike coats) and trousers. They wore no hats, but had long braids wound about their heads. Apparently the weather in the 12,000-foot valley was too hot for them!” Along the way they stopped at a village of the Porus people—Tibet's "untouchables"—who butchered animals and disposed of the dead, including conducting sky burials. They passed by the 24,000 foot high Chomo Lhari, “The Queen of the Snows.”

They reached Kagmar dak bungalow, Sandup's telephone station, where he was joined by his wife and child: “Sandup's wife was a great help to us all on the trip to Lhasa, and the baby girl became our mascot.” Tolstoy noted with amazement their “indifference to the discomfort of the trail.” Tolstoy paid a side visit by pony to a nearby monastery perched at 16,000 feet and was, by his reckoning, the first European ever to set foot inside it.

They arrived in Gyangtse, Tibet’s fourth-largest city and the center of its wool trade. They were met by a Sepoy detachment under the command of Major Gloyne. Here they were able to receive mail and hear reports of the progress of the war by radio, which was not going well for the Allies at this point. While in Gyantse, Dolan fell seriously ill with pneumonia. The expedition spent a month at Gyantse while Dolan recovered. To pass the time, the British and Tibetans played soccer matches, which the Tibetans always won because of the altitude. Electricity at the trade agency was provided by windmills, “enticing us to later evenings and long conversations with our Tibetan and British friends.”

When Dolan had recovered, they set out from Gyantse toward Lhasa, crossing the Tsangpo River (which becomes the Brahmaputra in India). On the way they were met by two soldiers, a sergeant and a private, who escorted them. They passed caravans carrying barley, salt and wool. In Tibet, custom dictated that smaller or less important caravans stand by the side of the road, hats doffed, to let the more important caravan pass by. The escorts assured that Tolstoy and Dolan would have the right-of-way for the remainder of the journey to Lhasa.

At Samding they took a detour to pay a brief visit to the "Diamond Sow" a six-year-old incarnate abbess; “an alert-faced solemn little girl with shorn locks seated on a high throne.” (TOS: 543) According to legend, in 1717 the monastery—then a nunnery—was besieged by Mongols. The abbess opened the gates and all the nuns were magically transformed into sows. Astonished, the Mongols laid down their weapons and departed. Dolan impressed the monks with his extensive knowledge of arcane Tibetan religious imagery, claiming to be an enthusiastic student of the religion: “Thereafter, this fact became known wherever he went and gained for our party a scholastic and religious respect.”

Twenty-five miles out from Lhasa, the Dalai Lama's delegation met them, led by a monk named Kusho Yonton Singhi, “who was to become our guide and inseparable adviser during our stay in the city of mystery.”

In Lhasa

They arrived in the broad plain surrounding Lhasa and crossed the only steel bridge in the country over the Kyi River, which flowed through the city. Just outside the city gates they were welcomed by a delegation led by Frank Ludlow, a former headmaster of the British school at Gyantse who had replaced Hugh Richardson as head of the British Mission. They would stay at Ludlow's residence during their time in Lhasa. At the city gate they were met by officials from the Dalai Lama's court, most notably George Tsarong (Tsarong Se Dabul Namgyal), the son of a famous Cabinet minister, and Dege Se, a royal prince and representative of the foreign office.

Ensconced in Lhasa, Tolsoy and Dolan took part in an endless series of receptions and tea parties hosted by Ludlow. “From that day we lived for weeks by a schedule. There was a definite procedure for whom to see, when, and in what order.” Officials, notables and dignitaries came from far and wide to greet the two Americans, including representatives of Nepal, Bhutan and Ladakh, who presented them with gifts of “wheat barley, flour, rice, meat, live sheep, butter and eggs.” Tolstoy and Dolan had mastered subtle Tibetan customs and etiquette, such as tossing rice over one's shoulder to appease the spirits. Custom dictated that they were not to call on any Tibetan officials until after their meeting with the Dalai Lama.

December 20th was chosen by the astrologers as the most auspicious date for an audience with His Holiness. Tolstoy and Dolan rode to the Potala palace, joined by representatives of the Foreign Office and escorted by a cavalcade of monks dressed in regalia. When they arrived, they were served tea and escorted by a procession of monks into the richly decorated throne room.

While monks and lay officials stood along the walls, the ten-year-old Dalai Lama sat on a couch in the center of the room flanked by his father and the Regent, who would govern Tibet until the young Dalai Lama came of age. Tolstoy and Dolan presented him with the letter from President Franklin Roosevelt. Following was the customary exchange of gifts, which included a silver framed portrait of President Roosevelt, a gold chronograph watch, and a silver ship replica2. The Dalai Lama accepted these gifts and politely inquired through an interpreter about the President's health. According to Ludlow, the Dalai Lama was quite taken with Tolstoy and “positively beamed on him throughout the interview.”

Tolstoy notes the historical significance of the occasion—the first ever meeting between the ruler of Tibet and representatives of the United States of America. It's rather mindblowing to think that present at this meeting was the very same Dalai Lama who is still around today and who has become such fixture in American and Western media for so many years. When the formal audience was over, Tolstoy and Dolan were escorted to the Dalai Lama's private chamber where they had an informal meeting with him. (TOS: 544)

The next several weeks in Lhasa were “devoted to making calls upon all the ecclesiastical and lay officials in the order of their rank and position, and presenting them with gifts...There followed a round of dinners, luncheons, and teas exchanged in both official and unofficial capacity.” One gets the impression that the Tibetans were genuinely charmed by the two American representatives, and that Dolan and Tolstoy were equally charmed by their gracious and obliging hosts.

On Christmas Day in 1942, Ludlow hosted a dinner party at his residence. Among the guests were George Tsarong and a leading noble, Phunkang Se, along with his wife Kuku, and his sister Kay. They ate turkey and played old-fashioned parlor games. Ludlow later commented, “I think Tolstoy and Brooke Dolan were astonished at the cheerfulness—and playfulness—of our little Lhasa lady friends.” Several subsequent rounds of parties followed over the next several weeks, with Dolan and Kay becoming especially close. (TOS: 544)

They visited the two largest monasteries in the world, Drepung and Sera, both near Lhasa. During their stay in Lhasa, Tolstoy and Dolan's deep affection for their Tibetan friends caused them to advocate for Tibetan independence against the stated policy of the United States’ government, which had to appease its Chinese allies. Tolstoy even suggested at one point that Tibet be invited to the peace conference at the end of the war, causing him to be reprimanded.

The new year festivities began in February, and Tolstoy and Dolan were on hand to witness them just as the Germans had done years earlier. Thousands of people and caravans flooded into the city, and the surrounding plain became filled with tents. Monks took over the administration of the city. Tolstoy and Dolan filmed the event and took thousands of photographs during their trip.

Dolan's journal is filled with marveling accounts of the holy city, of its monks and mendicants, of its great prayer wheels and giant fresco of the "Celestial Buddha of the East," of its fluttering votive flags and its wheeling phalanxes of geese and crane. By this time Dolan knew enough of the Tibetan language and the arcane imagery of Buddhism to impress his hosts as the Drepung monastery, the most important in Tibet, whose four colleges he visited during the Lunar Year festivities (which Tolstoy recorded on film). (TOS: 543)

As the celebrations wound down toward the end of the month they received permission from the Kashag to proceed to China. “Since further communication with the outside world would be impossible until we reached China, and since we faced dangerous unknown terrain, peril of bandits, and hazards of passes likely to be snow-blocked, we took great care in outfitting ourselves for the journey.” Sandup left the expedition at this point, promoting Lakhpa and Tommy, who would act as their new interpreter.

After three months they departed Lhasa in mid-March laden with goodwill gifts for President Roosevelt—the "King of America,"—including a Lhasa Apso presented by the "Lhasa ladies" which Dolan named Miss Tick. They were given a military send-off by an honor guard and served buttered tea in tents erected specially for the occasion. They were escorted by their Tibetan friends to the gates of the city where the white scarves of farewell were festooned upon them—by Tostoy's reckoning they were bedecked with over 200 of them by the time they left. They would wear at least one white scarf for the remainder of the journey. “Both Brooke and I felt a moment of sadness at leaving our friends behind, and we could see sincere emotions on their faces.” Concerned about roving bandits, the Tibetan government sent along a sergeant and five soldiers to accompany them as far as the border where a Chinese delegation would meet them.

For those of you wondering about the romantic aspect of our story—after Dolan had left for China, but was still inside Tibet, he learned that Kay was pregnant with his child.

To China

Tolstoy and Dolan struck out across the Reting Valley “with its evocative cloisters, luxuriant junipers, and chattering thrushes.” (TOS: 546). Streams were frozen and bridged with ice. On April 3 they crossed the divide of Langu La which separates the waters of the Brahmaputra and Salween rivers, arriving at Nagchu Dzong, the administrative capital of northern Tibet. Two days out of of Nagchu Dzong, they were struck by a snowstorm. Along the way they dined in the tents of nomad chieftains, astonishing them them with their radio.

As they headed across the northern plains following the trade route, they met a yak caravan coming the other direction laden with blocks of tea. The caravan had left Jyekundo with 1000 yaks and 25 ponies but had been reduced to 700 yaks and 15 ponies. They passed by a gallows with the head of an unfortunate bandit still hanging from it. They forded rivers and crossed precarious rope bridges suspended over vast gorges, pretty much exactly like the ones depicted in adventure movies (like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom). One particular bridge over the the Sok River was especially harrowing:

“The bridge was nothing but two chains over which was drawn a matting of saplings, with no railing or support along its sides. As the animals passed over it, the bridge swerved and shook like a ribbon in midair, 250 feet above the gorge. One man held each animal by the head and another held the tail...Even some of our native men crossed that bridge on all fours.”

Upon reaching the furthest extent of the Dalai Lama's jurisdiction, the escort turned back. They were now faced with a 200 mile journey to Jyekeundo through a lawless region where bandits and feuding nomad clans routinely preyed on caravans and travelers. They enlisted the help of a Pachen nomad chief to gather animals and drivers, but the new hires refused to proceed until they had hired another 25 men armed with rifles.

They began the steep climb to the Tsangne La pass at 16,000 feet, plunging with yaks through heavy snow: “The temperature was below freezing, and the ceaseless winds were the strongest yet encountered.” This was the political boundary between Tibet and China. On the other side of the pass, the Chinese delegation which was supposed to meet them never arrived. They flew American flags as they proceeded.

They now crossed into the vast region which was the birthplace of the great rivers of Asia—The Mekong, the Salween, and the Yangtze. Along the way, they enlisted the help of nomadic tribes who furnished them with transport and occasionally men armed with highly accurate and deadly slings. “One chieftain would tell us that another one was a bandit. In a few cases we had to resort to keeping a close watch on a chieftain and his men while they were traveling with us.” The winter of 1943 was especially harsh, and they pushed through frequent blizzards. On one occasion they were surrounded by horsemen and frightened them off with bursts of machine gun fire.

On May 6 they forded the Mekong River. They arrived at a Chinese garrison where they halted for a few days to rest and clean up. On May 15 they rode triumphantly into Jyekundo (modern Gyêgu) where Dolan's previous expedition had met its ignominious end years earlier. This time, however, the response would be quite different, and he would receive a hero's welcome:

“The commanding general, his staff, and the town's officials greeted us. A detachment of cavalry was lined up along the side of the road, and farther on monks of the local monastery were out with their band. A holiday was proclaimed in the city, flags and banners were displayed, and all the people turned out to greet us. Whenever we approached a native sitting in the street, he would rise in welcome.”

The Chinese Muslim general escorted them to the guesthouse where they would be staying. “Here we were really settled in style, with big Chinese beds made up with brand-new silk quilts, servants, a cook to attend us, and two armed guards to watch the gate.” One can only imagine what Dolan made of this given his previous experience.

They left Jyejundo, “escorted for several miles by the General, his staff an an honor guard.” They forded the swelling Yangtze river not far from its headwaters, killing sheep to make inflatable bags for their rafts. They camped near Shewu Gomba, a monastery perched on the side of a mountain. The land became more swampy, and they were frequently bogged down. As he had years earlier, Dolan stalked prey in the foothills, shooting several animals including a bear. They reached the freshwater lake of Gemoh Nor and crossed the Yellow River not far from its source. Despite it now being June, they were struck by yet another snowstorm. Referring to Dolan's harrowing experience years earlier, Tolstoy dryly noted, “This country was familiar to Captain Dolan, for in 1935 he had taken an expedition there to collect mammals for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.”

They now entered Koko Nor territory aided and escorted by Ngoloks: “These people, taller and more rugged than central Tibetans, are known as the fiercest tribe in this area.” Along the way they stopped at garrisons manned by Chinese Muslim cavalry soldiers. They skirted an arid stretch of desert and arrived in Hwangyuan on the 89th day of travel. Spring was coming. Another day's march brought them to Sining, the provincial capital. “The most memorable occurrence in Sining, outside of a visit with the Governor, was our visit to a Turkish bath, which we made our very first place of call in the city.”

From Sining they hired a truck and drove to Lanchow, where they stayed at a missionary compound. There they received their mail, which had been flown in from Chungking, including a congratulatory telegram from General Stillwell. Tolstoy and Dolan had made it. They had trekked 1,500 miles on foot, mule, and horseback, through horrible weather conditions and some of the harshest and most rugged terrain anywhere on earth. Both men received the Legion of Merit for their efforts.

The Aftermath

Although their journey from India to China was successful, as was their liaison with Tibetan officials including the Dalai Lama, the mission's ultimate aim was doomed from the start. The Tibetans would never allow the Allies to cross their territory unless there were a firm tripartite agreement between Tibet, India, and China; and China would never agree to such a thing because they would be forced to acknowledge Tibetan sovereignty. The Chinese government steadfastly refused to recognize Tibet's status as an independent nation despite its de-facto autonomy since 1912.

We know what subsequently happened. The Nationalists were defeated by the Communists and fled to Taiwan in 1949. In 1959, the People's Liberation Army invaded Tibet, forcing the Dalai Lama to flee into exile across the border to India. The mysterious Hidden Kingdom encountered by numerous explorers and travelers would be no more.

Tolstoy and Dolan remained in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater for the remainder of the War operating within China. Tolstoy was assigned to be camp commander of a special operations unit at Shanba, the northern base of the SACO—the Sino-Tibetan Special Technical Cooperation Organization, which worked closely with the Kuomintang's secret police. Tolstoy proposed to lead a joint Army-OSS mission to Mao Tse-Tung's headquarters in Yunnan. However, the Army was preparing its own Military Observer Group, known as DIXIE. Tolstoy requested a transfer to DIXIE, even showing the film he and Dolan made, Inside Tibet, to a senior Stillwell aid to convince him that he was the right man for the job. He lost out, however, due to his association with SACO as well as his status as a "White Russian."

Dolan went back to America, accompanied by Miss Tick (who was sadly killed in a car accident). He returned to China and transferred from the O.S.S. to the Army Air Force. He was appointed to the Military Observer Group in Yunnan—the same position Tolstoy had tried to get. The position was somewhat ambiguous, given that the Communists were rebelling against the Nationalists who were the United States’ allies. Dolan was upset at being passed over for promotion and, according to his roommate, drank heavily and had a habit of playing around with his .45 revolver: “Once I think by accident, he fired the gun, and the bullet bounced scarily around the cave in which we were quartered.” (TOS: 549)

Two months after his arrival in Yunnan, Dolan set off on a 600-mile trek to the Communist base at Fou-Ping. Leading a small party of Chinese guerrillas, he scouted the plains of Hopei province, pursued by the Japanese the entire time. On returning to Fou-Ping, he helped rescue a downed B-29 crew and fighter pilot, reaching Yennan in April. In Yennan, Dolan once again engaged in his passion for hunting, accompanied by Jimmy, his former hunter. For the second time he bagged an elusive takin: “You can imagine how Jimmy and I felt—to have killed another of those magnificent beasts after a lapse of eleven years!”

It's unfortunate that the accounts I have access to don't feature more from Dolan's perspective. He did keep a journal, excerpts of which were published in the 1980 edition of Frontiers, the annual of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. I have not been able to track it down, although I would very much like to read it. However, Tournament of Shadows gives us this passage written by Dolan which gives us some insight into his psyche. After he had felled the takin back in 1934, he reflected: “So I have come to the end of a long trail, and commingled with my jubilation is a trace of regret.”

“Every hunter to whom the chase means more than simply the trophy will sympathize. Some part of the glamour and mystery of mighty defiles and the hollow roar of tortured glacial streams, of bright and hostile bamboo jungles, and of misty crags is gone forever. The haunting spell of the mist and the secrets hidden in the dripping tunnels of high rhododendron forests are in part explored, in part exorcised by one lucky shot. So much the takin has meant to me and more...I have earned the memory of a long hard trail and brought to its climax with an almost poetical finality.” (TOS: 538-539)

That sense of ‘poetic finality’ would eventually catch up with him. He returned the Chongqing, where he ended his life on August 19, 1945, just days after Japan's surrender3. According to Tournament of Shadows, in the final weeks of his life, while still in uniform, he had attempted to return on his own to the Tibetan borderlands but was unable to see Kay or Lhasa again. According to contemporary sources, Kay and her child drowned near Gyantse a few years later.

We will never know, of course, what motivated Dolan to take his own life in Chongqing. It may be speculation on my part, perhaps more a reflection of my own psyche than his, but I feel that, deep down, he foresaw that the post-war world had no place for him. The timing is significant. He had spent a lifetime trying to stay on the margins of civilization by living in and for the wilderness, where he could truly be himself, free from the burdens, expectations and responsibilities of society. The "half-domesticated dog" had tried hard to domesticate himself but failed. As the war ran down and the world prepared for a future of peace and prosperity, Dolan could sense that the era of adventure was drawing to a close. What lay ahead was a world of suburbs and dinner parties, of golf and gray flannel suits, where there would be a Starbucks in Lhasa and Wi-Fi on Everest. It was a world he had spent a lifetime running away from, and now there would no longer be anywhere to escape to. So he made a fateful choice.

Dolan's many forays into Tibet surely must have made a deep impression on him. He was a keen student of Tibetan religion and spirituality long before it became known to the Western world. I like to think that when the clouds parted and mists lifted; when he gazed upon the mirrorlike surface of Koko Nor on a clear day, or when he caught a glimpse of the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas against the limitless blue sky, he recognized the impermanence of life and the transcendent nature of reality; and whatever fear he had felt, whatever pain he had suffered throughout his life faded away and, for a brief moment, he found peace.

Tolstoy was in Western China when he received the telegraph informing him of Dolan's death. According to Colonel David Longacre, who was with him at the time, “he was in total shock, as if he had been struck.” Years later, Tolstoy would write of his choice of Dolan to accompany him: “I have never regretted that decision for a moment, and my respect and recognition of Brooke's knowledge, character and ability grew from there on. Besides that, we became fast friends...” (TOS: 532-533)

BROOKE DOLAN II 1908-1945 R.I.P

O, Alas! Alas! Fortunate Child of Buddha Nature,

Do not be oppressed by the forces of ignorance and delusion!

But rise up now with resolve and courage!

Entranced by ignorance from beginningless time until now,

You have had more than enough time to sleep.

So do not slumber any longer, but strive after virtue with body, speech and mind!

—The BARDO THODOL

That's the end of our story. In the last installment, we'll wrap up the loose ends.

Next: The Novel Revealed.

SOURCES:

The above was written mainly from the account in Tournament of Shadows, chapter 22; and the account of the expedition written by Ilya Tolstoy in National Geographic, “Across Tibet From India to China,” in the August 1946 edition. That article has been transcribed by someone and can be read on this Web page. The film Inside Tibet can be found on YouTube here.

For another adventure story of an American plane crew downed in Tibet, see the book Lost in Tibet: The Untold Story of Five American Airmen, a Doomed Plane, and the Will to Survive by Richard Starks.

Apparently, the Tibetans felt the gifts were a bit miserly for such a great power as the United States. (TOS: 544)

There is some ambiguity about this. Tournament of Shadows asserts that Dolan died by suicide on August 19, but other sources say he was killed on August 29. Still other sources claim he was killed in action on an O.S.S. mission to rescue a downed Allied bomber crew. In any case, as both Tolstoy and his official obituary noted, “he died in the service of his country.”

Great post. Thank you.

The episode you retell here reminds me of the adventurous life of Sikunder Burnes. Craig Murray has written an amazing biography of his life as an East-India Company explorer and espionage agent during the era of the Great Game. From the blurb:

This is an astonishing true tale of espionage, journeys in disguise, secret messages, double agents, assassinations and sexual intrigue. Alexander Burnes was one of the most accomplished spies Britain ever produced and the main antagonist of the Great Game as Britain strove with Russia for control of Central Asia and the routes to the Raj. There are many lessons for the present day in this tale of the folly of invading Afghanistan and Anglo-Russian tensions in the Caucasus. Murray's meticulous study has unearthed original manuscripts from Montrose to Mumbai to put together a detailed study of how British secret agents operated in India.

https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2016/10/need-alexander-burnes/

Thanks again.