What is a State?

In chapter ten of The Dawn of Everything, Graeber and Wengrow make the case that the searching for the origin of the state is ultimately unproductive: "Much like the search for the 'origins of inequality', seeking the origins of the state is little more than chasing a phantasm." (427) The reason is because, according to them, European scholars who came up with the concept of 'the state' looked at the peculiar combination of factors that had come together in their own societies and projected them back into the past. The more ancient societies resembled European states, the thinking went, the more you could see the roots of what they called “state formation,” with its kings, taxes, bureaucracy, standing armies, territories, capital cities, and so forth.

This, they say, is counterproductive because no one has a very good handle on what a ‘state’ actually is. The most common definition was articulated by the German scholar Rudolf von Ihering and later became associated with Max Weber: a state is any institution that claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of coercive force within a particular territory. (359) However, even that very broad definition was not always accurate when it came to ancient states, and it tells us almost nothing about what ancient states were actually like. How can we possibly compare societies as diverse as Ancient Egypt, Shang China, Caral, Ancient Rome, Medieval France and Victorian Britain using this framework? Even today there is no universal definition for a state as its Wikipedia article notes.

Sometimes the idea of a "family resemblance" model is proposed. This idea was articulated by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Under the family resemblance model, "things which could be thought to be connected by one essential common feature may in fact be connected by a series of overlapping similarities, where no one feature is common to all of the things." (Wikipedia) The paradigmatic example is games, which encompasses everything from basketball, to chess, to golf, to poker, to Monopoly, to Angry Birds, to Dungeons & Dragons and Assassin’s Creed. By the time we have a suitable definition that encompasses everything we call a ‘game’ it tells us practically nothing about what any particular game is like or what makes something a ‘game’ beyond vague generalizations (e.g. ‘diversion’ or ‘enjoyment’).

Another method scholars have used is the "checklist" model. Under this model, if a phenomenon meets a certain number of predefined criteria, than it fits. This is often used to define similarly slippery concepts such as money or religion. Two different entities may check an entirely different set of boxes yet still check enough boxes to be included in the definition. This assumes, of course, that we can agree on a standardized set of criteria and what the threshold of belonging is.1

The Davids lament even the term ‘state’, attributing it to the sixteenth-century French lawyer Jean Bodin, and argue that the language of kingdoms, republics, and empires employed by Spanish explorers was better suited to describing these kinds of pre-modern and archaic political systems than more recent scholarly terms like ‘chiefdoms’ and ‘states’.

If it is possible to have monarchs, aristocracies, slavery and extreme forms of patriarchal domination even without a state (as it evidently was); and if it’s equally possible to maintain complex irrigation systems, or develop science and abstract philosophy without a state (as it also appears to be), then what do we learn about human history by establishing that one political entity is is what we describe as a ‘state’ and another isn’t? (361-362)

The Davids propose a different way of looking at the problem. If we discard our notions of what ‘states’ ought to entail and open our minds to other possibilities, they tell us, “there were far more interesting things going on than we might have ever guessed by sticking to any conventional definition of ‘the state’.” Rather than projecting our own sensibilities onto the past, or looking for vague similarities, we should instead evaluate ancient societies according to a different set of criteria.

Archaic States

Graeber and Wengrow tell us that there were “three primordial freedoms” which, "for most of history were simply assumed.” These were: 1.) the freedom to move; 2.) the freedom to disobey orders; and 3.) the freedom to rearrange the social structure. (362, 426)

In contrast, the Davids list three elemental forms of domination that emerge in any social context, from interpersonal relationships all the way up to group dynamics. These are 1.) control of violence, 2.) control of knowledge, and 3.) personal charm and charisma (365, 390). These are the three factors that allow some people or groups to dominate others. Of these methods, control over violence is the most reliable and charisma the most ephemeral.

These three elementary forms of domination manifest in institutional form as: 1.) sovereignty; 2.) administration; and 3.) charismatic politics. (439) It is these features, they say, which distinguish what we normally refer to as 'states.'

In the kinds of modern, bureaucratic states that dominate the world today, these take the forms of: 1.) A system of laws, courts, and regulations backed by military and police; 2.) An impersonal bureaucracy that usually exists apart from any particular leader; and 3.) A competitive political playing field. While we normally think of elections as validating the legitimacy of the state (“we get to choose our leaders!”), in a trenchant passage the Davids remind us that what we call democracy is fundamentally different from what ancient peoples would have understood by that term. Instead, they say, modern “democracy” is merely a popularity contest waged among elites to determine who gets to wield power:

…democracy, in modern states, is conceived very differently to, say, the workings of an assembly in an ancient city, which collectively deliberated on common problems. Rather, democracy as we know it is effectively a game of winners and losers played out among larger-than-life individuals, with the rest of us reduced largely to onlookers. (367)

The Davids argue that these three elemental forms of domination all have separate origins, so there is no reason to think that all of them must be present in any given society or come together in exactly the same way. Furthermore, there is no set sequence that they must emerge. Many different societies developed these elementary forms of domination to different degrees and in different ways, which is why the term 'state' is so difficult to accurately define.

They remind us that even today supranational bureaucracies exert a considerable degree of control over the world's economies (e.g. The International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank) without any corresponding principle of sovereignty. Similarly, there are states which have lost the monopoly of violence over parts of their territory such as Mexico and Ecuador (even though such violence is not considered legitimate), yet are still considered to be states. Then there are international corporations which have the all the economic power of nation-states and feature administration and competitive politics, but lack sovereignty even as they undermine the sovereignty of existing nation-states.

Just as access to violence, information and charisma defines the very possibilities of social domination, so the modern state is defined as a combination of sovereignty, bureaucracy, and a competitive political field...there is no actual reason why these principles should go together, let alone reinforce each other in the precise fashion we have come to expect from governments today. For one thing, these three elementary forms of social domination have entirely separate historical origins... (367)

The Davids go on to describe to what extent these elementary forms of domination were present or absent in a number of ancient civilizations. In certain instances, only one of these forms was developed to a high degree. The examples they cite are the Olmec civilization in central Mexico and Chavín de Huántar in Peru, a precursor kingdom to the Inca. Both of these "empires" lacked many of the features we associate with states like standing armies, fortifications, administration, a monopoly on violence, or a hierarchy of command. Yet both of them developed one particular form of domination to a high degree: charismatic political competition and spectacles in the Olmec case, and the control of images linked to esoteric knowledge in the case of Chavín.

Clearly our use of the word 'empire' here is about as loose as it could possibly be. Neither was remotely similar to, say, the Roman or the Han, or indeed the Inca or the Aztec Empires. Nor do they fulfill any of the important criteria for 'statehood'—at least not on most standard sociological definitions (monopoly of violence, levels of administrative hierarchy, and so forth). The usual recourse is to describe such regimes instead as 'complex chiefdoms', but this too seems hopelessly inadequate—a shorthand way of saying, 'looks like a state, but it isn't one.' This tells us precisely nothing. (390)

In other words, if these were 'states' in any sense at all, then they are probably best defined as seasonal variations of what Clifford Geertz once called 'theatre states', where organized power was realized only periodically, in grand but fleeting spectacles. Anything we might consider 'statecraft', from diplomacy to the stockpiling of resources, existed in order to facilitate the rituals, rather than the other way round. (386)

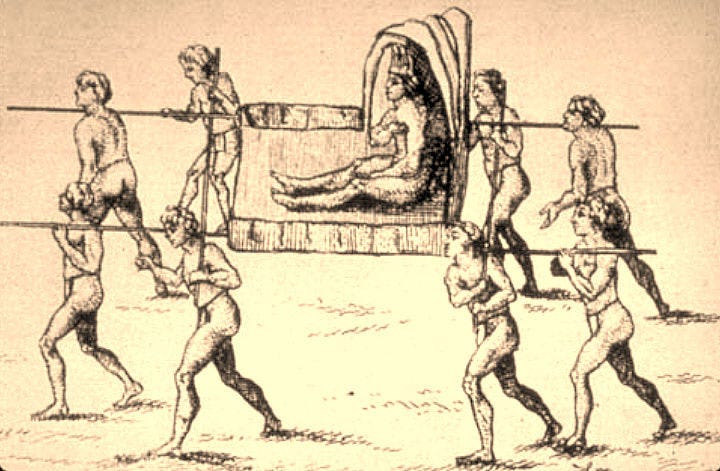

In other instances, sovereignty emerged without anything resembling a ‘state’. They list the examples of the Natchez People of Louisiana and the Shilluk Kingdom of East Africa. In both of these societies, the supreme leader (The Great Sun for the Natchez, the reth for the Shilluk) was entitled to enact arbitrary violence over people—that is, they were subject to no higher temporal authority than their own. However, these leaders lived in what was effectively a cocoon surrounded by family members and retainers, and therefore sovereignty was confined to the ruler's immediate presence. There was no way of effectively delegating sovereignty, so most people, they tell us, simply avoided hanging around the ruler (why didn't everyone?).

The Natchez Sun, as the monarch was known, inhabited a village in which he appeared to wield unlimited power. His every movement was greeted by elaborate rituals of deference, bowing and scraping; he could order arbitrary executions, help himself to any of his subjects’ possessions, do pretty much anything he liked. Still, this power was strictly limited by his own physical presence, which in turn was largely confined to the royal village itself. Most Natchez did not live in the royal village; outside it, royal representatives were [not]…treated…seriously. (156)

The divine kingship of the Shilluk, a Nilotic people of East Africa, worked on similar lines: there were very few limits on what the king could do to those in his physical presence, but there was also nothing remotely resembling an administrative apparatus to translate his sovereign power into something more stable or extensive: no tax system, no system to enforce royal orders, or even report on whether or not they had been obeyed. (368)

The Davids describe these as ‘first order regimes.’ These were societies in which one of the three elementary forms of domination was developed to a high degree. (391) The two other forms of domination may have been present as well, but in a much less developed or institutionalized form.

In ‘second order regimes’ such as Pharaonic Egypt or the Andean kingdom of Tahuantinsuyu, a system of administration became wedded to sovereignty such that sovereignty could be delegated and projected over a wide swath of territory. These examples are taken as the “conventional” model of state formation. Alternatively, in other regimes, charismatic politics might become wedded to either sovereignty or administration:

First-order regimes like the Olmec, Chavin or Natchez each developed only one part of the triad. But in the typically far more violent arrangements of second-order regimes, two of the three principles of domination were brought together in some spectacular, unprecedented way. Which two it was seems to have varied from case to case. Egypt's early rulers combined sovereignty and administration; Mesopotamian kings mixed administration and heroic politics; Classic Maya ajaws fused heroic politics with sovereignty.

We should emphasize that it's not as if any of these principles, in their elementary forms, were entirely absent in any one case; in fact, what seems to have happened is that two of them crystallized into institutional forms—fusing each in a way as to reinforce one another as the basis of government—while the third form of domination was largely pushed out of the realm of human affairs altogether and displaced on to the non-human cosmos. (413)

The Davids tell us that recordkeeping in second-order regimes began in the service of “otherworldly affairs,” such as calendrical observations or divination, rather than for economic management. This was true of the Mayans, for example, whose remarkably precise observations of the heavens never developed into a bureaucracy; or Shang China, where cracks in tortoise shells were originally used to communicate with dead ancestors. In ancient Egypt, the earliest writing was used for funerary purposes to assist the dead in their passage to the afterlife. In Chavín de Huántar, communication with transcendental deities was recorded in white granite and black limestone. This contradicts the idea that bureaucracies initially developed to coordinate economic activities as is often portrayed; rather, that appears to have been a later development.

[W]hen early regimes...base their domination on exclusive access to forms of knowledge, these are often not the kinds of knowledge we ourselves would consider particularly practical...In fact, the first forms of functional administration, in the sense of keeping archives of lists, ledgers, accounting procedures, overseers, audits and files, seem to emerge in...ritual contexts: in Mesopotamian temples, Egyptian ancestor cults, Chinese oracle readings and so forth...

So one thing we can now say with a fair degree of certainty is that bureaucracy did not begin simply as a practical solution to problems of information management, when human societies advanced beyond a particular threshold of scale and complexity…farmers are perfectly capable of co-ordinating very complicated irrigation systems all by themselves, and there’s little evidence…that early bureaucrats had anything to do with such matters. (419-420)

The Davids point out that the first signs of administration in Mesopotamia show up two millennia before either cities, states or monarchies, meaning that bureaucracy originally emerged in small communities. This leads them to conclude that administration began not as a means of extracting wealth, but in the service of an explicit ideal of equality and reciprocity.

They examine a site called Tell Sabi Abyad, where clay tokens were used as part of a sophisticated accounting system. The use of these tokens is associated with a higher degree of uniformity in terms of housing and craft production across Mesopotamia. Clay tokens kept track of each village's reciprocal contributions. A system using knotted strings called khipu was used by the Inca to keep track of commodities and record a census of subject peoples, most of whom lived in small settlements: “In some ways, people living in small-scale communities began to act as if they were already living in mass societies of a certain kind, even though nobody had ever seen a city." (422)

Yet, despite these apparently egalitarian origins, bureaucracies gradually developed into instruments of domination once they became wedded to sovereignty. Bureaucracy in principle reduces people and things to abstract units and does not take into account the unique circumstances of each particular individual or household. Instead, bureaucracy develops impersonal rules which, when applied uniformly, can easily become instruments of tyranny, control and oppression:

Of course, the danger of such accounting procedures is that they can be turned to other purposes: the precise system of equivalence that underlies them has the potential to give almost any arrangement, even those founded on arbitrary violence an air of even-handedness and equity. That is why sovereignty and and administration make such a potentially lethal combination, taking the equalizing effects of the latter and transforming them into tools of social domination, even tyranny...frequently the most violent inequalities seem to arise…from…fictions of legal equality.

Perhaps this is how sovereignty manifests itself, in bureaucratic form. By ignoring the unique history of every household, each individual, by reducing everything to numbers one provides a language of equity—but simultaneously ensures that there will always be some who fail to meet their quotas, and therefore that there will always be a supply of peons, pawns or slaves…The first establishment of bureaucratic empires is almost always accompanied by some kind of equivalence system run amok...It's the addition of sovereign power, and the resulting ability of the local enforcer to say, 'Rules are rules; I don't want to hear about it' that allows bureaucratic methods to become genuinely monstrous. (424-6)

In other societies, sovereignty manifested as acts of ritual care and devotion for the ruler. The Davids suggest that this was the case in Old Kingdom Egypt, Shang China, and Inca Peru. In these societies, the birth of something like ‘the state’ appears to have been accompanied by phenomena like mass human sacrifice, mummification, and the erection of large funerary monuments, all ostensibly acts of caring and devotion which paralleled internal household dynamics on a civilizational scale. Both Egyptians and Peruvians mummified their rulers and continued to venerate them after death. Dead rulers continued to tour their kingdoms. The dead ruler’s cult, then, became an instrument of state-building.

When sovereignty first expands to become the general organizing principle of a society, it is by turning violence into kinship. The early, spectacular phase of mass killing in both China and Egypt, whatever else it may be doing, appears to be intended to lay the foundations of what Max Weber referred to as a 'patrimonial system': that is, one in which all the kings' subjects are imagined as members of the royal household, at least to the degree that they are all working to care for the king.

Turning erstwhile strangers into part of the royal household, or denying them their own ancestors, are thereby ultimately two sides of the same coin. Or to put things another way, a ritual designed to produce kinship becomes a method of producing kingship.

In the case of Egypt, it seems, ‘state formation’ began with some kind of Natchez or Shilluk-like principle of individual sovereignty, bursting out of its ritual cages precisely through the vehicle of the sovereign’s demise in such a way that royal death ultimately became the basis for reorganizing much of human life along the length of the Nile. (402-3)…If we are trying to understand the appeal of monarchy as a form of government…then it likely has something to do with its ability to mobilize sentiments of a caring nature and abject terror at the same time. (416)

Both the veneration of dead rulers and the establishment of bureaucratic systems of management in the service of maintaining equity are ostensibly acts of care. So, too, did owners of household slaves look after them, as did the slaves for their masters. This leads the Davids to posit, "Perhaps this is what a state actually is: a combination of exceptional violence and the creation of a complex social machine, all ostensibly devoted to acts of care and devotion." (408) In these societies, both the rulers and the ruled became intertwined in mutually-dependent relationships of caring and devotion which sometimes turned violent, like an abusive relationship or a kind of ‘Stockholm syndrome’, where ‘love’ was ultimately the glue that held everything together.

These various forms of domination not only came together in various ways, but also frequently broke apart. The Davids describe how breakdowns in one or more of the elementary forms of domination ushered in so-called 'intermediate periods' or 'dark ages', and suggest that these terms betray an inherent bias toward ‘civilization’ as defined by grand monuments, writing, battles, and hierarchy carried out by ever-larger populations: “In ancient Egypt, as so often in history, significant political accomplishments occur in precisely those periods (the so-called 'dark ages') that get dismissed or overlooked because no one was building grandiose monuments in stone.” (418) During periods when sovereignty broke down, “heroic” politics tended to reassert itself.

This chapter is broad and discursive, with lengthy digressions into how the three elementary forms of domination came together, or failed to. There were societies which featured bureaucracy but no concept of sovereignty such as Mesopotamian city-states. In others cases we see sovereignty and charismatic competition for leadership as among Mayan warrior-kings and Chinese warlords, but recordkeeping was strictly confined to a religious context. The Pharaohs and the Inca combined sovereignty with administration, while in other societies you had all-powerful rulers presiding over court structures who possessed neither standing armies nor bureaucracy; while still other societies featured esoteric knowledge in the hands of ritual specialists but nothing like sovereignty or charismatic politics. The Davids conclude:

The state, as we know it today, results from a distinct combination of elements—sovereignty, bureaucracy and a competitive political field—which have entirely separate origins...these elements directly map on to basic forms of social power which can operate on any scale of human interaction, from the family or household all the way up to the Roman Empire or the super-kingdom of Tawantinsuyu. Sovereignty, bureaucracy and politics are magnifications of elementary types of domination, grounded respectively in the use of violence, knowledge and charisma. Ancient political systems—especially those…that elude definition in terms of 'chiefdoms' and 'states'—can often be understood better in terms of how they developed one axis of social power to an extraordinary degree…These are what we termed 'first order regimes'.

Where two axes of power were developed and formalized into a single system of domination we can begin to talk of 'second-order regimes'. The architects of Egypt's Old Kingdom, for example, armed the principle of sovereignty with a bureaucracy and managed to extend it across a large territory. By contrast, the rulers of ancient Mesopotamian city-states made no direct claims to sovereignty, which for them resided properly in heaven…Instead they combined charismatic competition with a highly developed administrative order. The Classic Maya were different again, confining administrative activities largely to the monitoring of cosmic affairs, while basing their earthly power on a potent fusion of sovereignty and inter-dynastic politics. (507-508)

Their major point is that there is no singular “origin” for ‘the state’, nor is it something that has been continually developing since the Stone Age. In reality, 'states' are best defined as an amalgam of overlapping organizational principles which reinforce domination that sometimes come together and just as commonly fall apart. Modern states are really more of a historical accident, they tell us—and one which is currently coming apart again—rather than the inevitable culmination of human society or its final form.

North America

The Davids examine the history of North America in chapter eleven, which they say contradicts the notion that states, war and bureaucracy are inevitable once people start farming and cities are established. They describe the fall of the Mississippian culture and the abandonment of Cahokia, which they say provides an alternative to the kind of “arrow of history” narrative that leads inexorably to states. The “backlash” against Cahokia, they say, caused successor societies like the Iroquois to enshrine the primordial freedoms into their cultural sensibilities in order to prevent something like an incipient grain state from ever forming again, unlike other parts of the world:

Our aim here is to understand the local roots of the indigenous critique of European civilization, and how those roots were entangled in a history that began at Cahokia or perhaps considerably earlier (455)…Whatever happened in Cahokia, the backlash against it was so severe that it set forth repercussions we are still feeling today. (482)

These sensibilities are what formed the basis of the ‘indigenous critique’ with which they began the book, and which was most eloquently expressed by the Wyandot statesman Kandiaronk. Kandiaronk’s words and ideas were supposedly conveyed by the Baron Lahontan (in the guise of ‘Adario’) directly to the intellectuals of Europe causing them to question their existing social arrangements, which had previously been taken for grated. The end result, they say, was the Enlightenment.

[T]he ideals expressed by thinkers like Kandiaronk, only really make sense as the product of a specific political history: a history in which questions of hereditary power, revealed religion, personal freedom and the independence of women were still very much matters of conscious debate, and in which the overall direction, for the last three centuries at least, had been explicitly anti-authoritarian. (482)

These chapters are the culmination of the war on teleology that the Davids have been waging throughout the entire book, where nothing predetermines the form that our modern societies must take, contra the teachings of Big History. Neither farming, nor population size, nor density, nor cities, nor sedentism, nor specialization and technological sophistication—none of these predetermined any particular end result, they tell us, based on their expansive survey. This, they say, opens up other possibilities that were previously seen as impossible or unthinkable due to post-Enlightenment myths which were explicitly designed to counter the indigenous critique. These, however, are merely secular retellings of the biblical Garden of Eden story, or the Fall from Grace.

If anything is clear by now, it's this. Where once we assumed 'civilization' and 'state' to be conjoined entities that came down to us as a historical package (take it or leave it, forever), what history now demonstrates is that these terms actually refer to complex amalgams of elements which have entirely different origins and which are currently in the process of drifting apart. Seen this way, to rethink the basic premises of social evolution is to rethink the very idea of politics itself. (431)

Conclusion

It should come as no surprise by now that the major criticism I have here is the same as nearly every other topic in the book: the ideas they are presenting as being somehow revelatory aren't really all that different from mainstream scholarship.

While it may be the case that Enlightenment thinkers looked for the seeds of their own societies in ancient states, modern scholars no longer do that. In fact, if anything scholars today emphasize the uniqueness of factors that came together which resulted in the post-Westphalian nation-states of Western Europe. It’s commonly acknowledged that these arrangements were highly contingent and not applicable to other parts of the world, much less to civilizations in the distant past.

Their idea of looking at states as amalgamations of fundamental sources of domination is useful, but it's not unique. Michael Mann in The Sources of Social Power identified four fundamental sources of power he described according to his IEMP model: Ideological, Economic, Military and Political. That framework has since come to be widely accepted. Peter Turchin has modified these slightly as Coercive Power, Economic Power, Administrative Power, and Ideological Power, or Persuasion. Similarly, Steven Lukes claimed that power is exercised in three ways: decision-making power, non-decision-making power, and ideological power, where the latter can often make people advocate for what goes against their own best interests.

On Social Power (Cliodynamica)

Lukes on power (Understanding Society)

This parallels another criticism: there is a huge and burgeoning literature about the emergence of states out there, but they do not seem to engage with it very much. For example, there is nothing about circumscription theories or redistributive chiefs, even to deny the validity of such theories. Evolutionary approaches, which focus on the relative ability of certain configurations of power to expand at the expense of others, are also not considered.

Their argument against ‘the state’ seems to be as much of a semantic one than anything else. Once again, as with their earlier critique of evolutionism, they seem to be hung up on terms of art which are only loosely applied. I doubt the use of the term ‘state’ deludes scholars into thinking that the Aztec Triple alliance, the Kingdom of Benin, and the Sun King’s France are all somehow identical or related. Similarly, the “ladder of progress” model has long since been abandoned. I’m certainly okay with bringing back terms like kingdoms, empires, republics, democracies and oligarchies. Our language describing political systems could use some refining.

Although they never mention it explicitly, Francis Fukuyama's “The Origins of Political Order” feels like a specter haunting the entire chapter. Fukuyama is known for his "End of History" thesis which argued that liberal electoral democracy and competitive markets are the end state for human social organization. All countries around the world supposedly aspired to this platonic ideal of "a competent state, strong rule of law, and democratic accountability," which Fukuyama describes as "getting to Denmark.” He sees China as the first true ‘state’ since it developed an impersonal bureaucracy based on competitive examination rather than kinship structures. As a result, The Origins of Political Order does often read like a teleological treatise where Denmark was always where we were headed ever since we climbed down from the trees, whether intentional or not.

I think one of the reasons Graber and Wengrow are so obsessed with Big History is because these narratives have become extremely popular in recent years, especially among armchair intellectuals. It becomes a kind of intellectual straitjacket foreclosing other ways of looking at history and making our current circumstances look inevitable. Big History's oversimplified narratives have become especially popular in Silicon Valley, where they provide an intellectual justification for Silicon Valley's sociopathic ideology of top-down control, extreme wealth inequality, and libertarian capitalism.

There’s always this perennial debate over ‘determinism’ whenever some external factor comes into play, be it climate, geography, natural resources, or whatever. Anything other than ‘voluntary choice,’ where we make our own circumstances one hundred percent is derided as ‘determinism.’ It reminds me of that stupid American phrase: “there’s no such thing as luck.” Of course there is. By definition, if it’s out of your control, then it’s luck—that’s what the word means, after all. There’s always some external factor which can be consigned to that category. Knowing where exactly to draw that line, however, can be quite difficult.

How inevitable, really, were the type of governments we have today, with their particular fusion of territorial sovereignty, intense administration and competitive politics? Was this really the necessary culmination of human history? (446)

In the case of the Americas, we actually can pose questions such as: was the rise of monarchy as the world’s predominant form of government inevitable? Is cereal agriculture really a trap, and can one really say that once the farming of wheat or rice or maize becomes sufficiently widespread, it’s only a matter of time before some enterprising overlord seizes control of the granaries and establishes a regime of bureaucratically administered violence? And once he does, is it inevitable that others will imitate his example? Judging by the history of pre-Columbian North America, at least, the answer to all these questions is a resounding ‘no’. (451)

A lot of weight comes to rest on North America as an example of sidestepping state formation. Yet North America was atypical: it had relatively low population density and even pack animals were absent. Despite this, there were still plenty of examples of kings, ritual specialists and proto-states. It’s true that the Mississippian culture eventually collapsed, as did many others which turned their back on agriculture. But, as the Davids themselves point out, so too did Old World regimes like ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and pre-Classical Greece, among others. Yet the elementary forms of domination eventually reasserted themselves. How do we know that the same thing would not have happened in North America? The arrival of Europeans and European diseases forever put an end to that experiment. As Walter Scheidel notes in his review, “Detours, even collapses, cannot be used to invalidate the story: they are simply part of it.”

Which brings up another recurring objection: They focus too much on edge cases rather than paradigmatic examples. That’s a worthy effort, but it’s not the thorough “debunking” of anthropological theory that so many people seem to think it is. While it could be argued that we could have taken different paths than the ones which have led us to the present moment, that's a counterfactual that’s very difficult—if not impossible—to prove. We can’t know what might have happened. Perhaps that’s better left to science-fiction authors. All we can do is study what did happen and try to learn something from it.

All of this raises a pertinent question: why are states the dominant political form today? The Davids show little curiosity about this question nor do they provide an answer. In the end, they only shrug their shoulders and acknowledge that it is the case while pondering whether it really had to be so.

I think their approach of looking at politics through the lens of fundamental forms of domination, which sometimes coincide and sometimes don’t, is a useful one. So, too, is their emphasis on how ancient societies differed from our own. Their concept of first, second, and third-order regimes is a helpful one, too. But otherwise it’s hard to know what to take away from these chapters. They seem to be throwing out a bunch of ideas trying to see which ones will stick. Are states the product of combining sovereignty with bureaucracy? Are they a result of interactions between agrarian polities and ‘heroic’ societies? Do they start out as seasonal theater where some people forget that it’s all just play? Are they acts of nurturing and care gone bad? All of the above? All of these ideas make an appearance, often prefaced with ‘perhaps’, making it difficult to tell exactly what their overall theory is. If the concept of ‘states’ is not valid from a historical or anthropological standpoint, than what should we replace it with?

Fukuyama offers the following checklist in The Origins of Political Order:

1.) First, they possess a centralized source of authority, whether in the form of a king, president of prime minister. The source of authority deputizes a hierarchy of subordinates who are capable, at least in principle, of enforcing the rules on the whole of the society. The source of authority trumps all others within its territory, which means that it is sovereign. All administrative levels, such as lesser chiefs, prefects, or administrators, derive their decision-making authority from their formal association with the sovereign.

2.) Second, that source of authority is backed by a monopoly on all the legitimate means of coercion, in the form of an army and/or police. The power of the state is sufficient to prevent segments, tribes, or regions from seceding or otherwise separating themselves (This is what distinguishes a state from a chiefdom.)

3.) Third, the authority of the state is territorial rather than kin based. Thus France was not really a state in Merovingian times when it was led by a king of the Franks rather than the king of France. Since membership in a state does not depend on kinship, it can grow much larger than a tribe.

4.) Fourth, states are far more stratified and unequal than tribal societies, with the ruler and his administrative staff often separating themselves off from the rest of society. In some cases they become a hereditary elite. Slavery and serfdom, while not unknown in tribal societies, expand enormously under the aegis of states.

5.) Finally, states are legitimized by much more elaborate forms of religious belief, with a separate priestly caste as its guardian. Sometimes that priestly class takes power directly, in which case the state is a theocracy; sometimes it is controlled by a secular ruler, in which case it is labeled caesaropapist; and sometimes it coexists with secular rule under some form of power sharing.

“With the development of the state, we exit out of kinship into the realm of political development proper…Once states come into being, kinship becomes an obstacle to political development, since it threatens to return political relationships to the small-scale, personal ties of tribal societies. It is therefore not enough to develop a state; the state must avoid retribalization or what I label repatrimonialization.” (OPO: 80-81)

Walter Schiedel defines it thusly: "Modern scholars have come up with a wide variety of definitions that seek to capture the quintessential features of statehood. Borrowing elements of several of them, the state can be said to represent a political organization that claims authority over a territory and its population and resources and that is endowed with a set of institutions and personnel that perform governmental functions by issuing binding orders and rules and backing them up with the threat or exercise of legitimized coercive measures, including physical violence." The Great Leveler, p. 43

Yes I am still here and I still have a job. Write a report