The End of Growth and The Zero Sum World

Is the rise of fascism connected to the end of economic growth? And what is the real culprit?

I’d like to feature a couple of articles that, taken together, paint a larger picture and reflect some of the topics I’ve been thinking a lot about lately.

The first is this one from a bloke called Paul Kedrosky: Life Under Two: Debt, Deficits, and the AI Discontinuity

While I agree with much of the basic premise of his article, there are parts where I think it goes astray.

The author points out that economic growth in the United States has slowed down in recent years. In the past, growth used to average over three percent per year, minimum. However, in recent years, US growth has averaged under two percent, hence the title of the post.

The author then goes on argue that this slowdown is key to many of the social and political phenomena that we’ve been witnessing over the past few years in the United States, to wit:

This shift from robust to modest growth affects...everything. It is behind, in large part:

The rise of populism

Anti-immigrant sentiment

DOGE

A return to tariffs

Soaring U.S. deficits and debt

The author points out that, although this slowdown seems relatively small in degree, it has huge impacts:

The difference between 3% and 2% annual growth is stark. At the higher rate, over ten years, you have:

$3.36 trillion larger economy

$3.7 trillion more in tax revenue

6 million more jobs

Significantly higher real incomes

The gap directly affects opportunities, wage growth, tax revenue, social services, health care, solvency, and optimism about the future. Growing quickly and being awash in income makes people optimistic about the future; the opposite does...the opposite.

Critics of capitalism have long pointed out that capitalism requires growth because the system is structurally designed though its own internal logic to concentrate wealth into fewer and fewer hands. However, if there is growth, living standards can continue to rise at the margins for most people which justifies the grotesque inequality engendered by the system.

In the conventional formulation, the staggering fortunes of these magnates are justified as a way of producing higher living standards for the masses, and any constraint on their wealth or prerogatives, the argument goes, will cause living standards to fall for all of us, not just for them. This justification, however, relies on continued growth.

However, without this reliable growth, people fight amongst themselves for scarce resources leading to ever-increasing antagonism. And this leads to one of the core features of the MAGA movement: zero-sum thinking.

Under zero-sum thinking, any gain for someone necessarily means a loss for someone else. This has been identified as a core feature of Trump’s world view, and hence of the entire MAGA movement (my emphasis):

Americans built their self-image and expectations around decades of strong growth, trusting each generation would surpass the previous one. Sub-2% growth erodes this assurance, shifting psychology from abundance toward scarcity, and even zero-sum thinking. When people don't see abundance they stop sharing. And Americans have stopped sharing.

The most obvious expression of this thinking is with global trade. Trade is commonly seen as the quintessential positive-sum game in which all parties benefit from repeated interactions—the exact opposite of a zero-sum game. However, Trump has repeatedly said that countries which have a positive trade deficit with the US are “ripping us off.” A deficit means the US is somehow being “cheated” and this explains the logic behind sky-high tariffs. “They took our jobs,” goes the refrain, as if there were a fixed pool of jobs in the world.

This perception underlies everything in the MAGA world view. Under this view, if immigrants are getting anything at all, then Americans must be being deprived of those exact same things. If a refugee or welfare benficary receives any benefits whatsoever, it must be taken away from American citizens. If black person gets a job, it must have been taken away from a more qualified white person who rightfully deserved that job instead (which is portrayed as “DEI policies”). Trump claimed that hurricane relief aid destined for victims of hurricanes in North Carolina was being diverted to immigrants instead, leading to militias attacking FEMA workers and death threats against meteorologists. But all of this is fundamentally a reflection of zero-sum thinking.

This perception even applies to things like status: if women rise in status, it necessarily means that men’s standing must fall. That is, status is conserved: there is no such thing as everybody benefiting. There cannot be a win-win. That concept is utterly foreign to the MAGA—and to the conservative—mentality. My gain is your loss, and your loss is my gain, period. And they can only gain at the expense of someone else—someone they see as their enemy (women, foreign, gays, “radical leftists,” etc.):

In her 2024 memoir, Freedom, former German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, wrote of the then US president, Donald Trump:

“He assessed everything from the perspective of the real-estate developer he had been before entering politics. Each piece of property can be allocated once. If he didn’t get one, he got another. That’s how he saw the world. For him, all countries were in competition, and the success of one meant the failure of another. He didn’t believe that cooperation could increase prosperity for everyone.”

Now consider the following ideas that have been all too common in recent American political rhetoric:

If other countries grow wealthier, then the United States must grow poorer.

If immigrants win, then residents must lose.

If women win, then men must lose.

If gay people win, then straight people must lose.

If transgender people win, then cisgender people must lose.

Those propositions have two things in common: (1) they all are examples of zero-sum thinking, and (2) they are all false.

Despite what politicians claim and often do, society is not zero-sum (London School of Economics)

While they may be false, they are increasingly accepted by more and more Americans leading to a “crabs-in-a-bucket” mentality. This Guardian profile of voters in Youngstown, Ohio includes an interview with a worker and union official laid off from her job in an automobile plant:

[Sonja] Woods, like many in Youngstown, sympathises with Trump’s zero-sum view of the world – that if one group is benefiting, it is usually at the expense of another. Seeing Afghan refugees move into government-subsidised housing when she had to finance her move to Kentucky infuriated her. Reading about Biden’s plans to forgive student debt when she paid off her daughter’s student loans in full struck her as deeply unfair…

The article goes on to note that, despite securing a new high-tech job due to Biden’s economic policies, she planned to vote against him:

She was unwilling to give the Biden administration much credit for spurring clean-energy businesses like her current employer, and she was too angry at GM to place much, if any, blame on Trump for allowing the old plant to close. What she saw, rather, was a general indifference from the political class, especially now that Ohio is no longer regarded as a swing state. “Nobody showed up in Youngstown this time, not Trump or Kamala,” she observed. “There are a lot of bitter people, and I’m one of them.”

‘There are a lot of bitter people here, I’m one of them’: rust belt voters on why they backed Trump again despite his broken promises (The Guardian)

Angry, bitter people—these are the core constituency of the MAGA movement. And, in many cases, they have reasons to be angry. But instead of trying to make her life and the lives of people in her community better, she, like many Americans, has instead embraced the politics of resentment and destruction.

The Trump administration’s single-minded obsession with brutalizing and terrorizing immigrants is also very much in line with this zero-sum thinking, as Kedrosky points out (my emphasis):

With rapid expansion, foreign competition and immigration offer benefits. Displaced domestic workers can easily transition to new sectors, and immigrants fill labor shortages. But once growth falters, everything goes into reverse.

Losing one's job and hoping that the economy can handle it feels like a bad bet. Workers displaced by trade struggle to find comparable opportunities. Communities undergoing rapid demographic shifts feel resource pressure. Immigration restrictions and higher tariffs become politically attractive means to maintain existing conditions. They are zero-sum responses to scarcity, predictable during Life Under Two.

Immigration restrictions and tariffs are predictable, zero-sum responses to scarcity… Lower growth explains rising political polarization. When growth was strong, expansive revenues funded both new programs and tax cuts. Rising wages benefited workers and shareholders alike, making immigration economically beneficial.

Under slower growth, policies become inherently competitive. Tax cuts reduce funding for public programs. Wage increases for some imply job losses for others. Immigrants are seen as competition for jobs, even when they are not…

Kedrosky further ties this to the drive for budget cuts, including the farcical “department of government efficiency" spearheaded by unelected oligarch Elon Musk.

Indeed, as I’ve often pointed out, the conservative/libertarian view of economics is that money is an inherently scarce resource and there is a limited pool of it in the world. Thus, we “cannot afford” to do the things we want or need to do, and if money is diverted to one purpose, it must necessarily be taken away from something else. From this perspective, the money that the government collects in taxes is taken away from “taxpayers” in a zero-sum contest for limited funds. This is why “small government” is inherently better in their view.

This—utterly incorrect—view of money is what’s behind the notion that eviscerating the federal government leads to “savings” which will somehow benefit the “taxpayers.” However, as MMT accurately describes, there is no more a scarcity of money than there is a scarcity of points in a basketball game—the only limitation is the amount of real resources we have to accomplish all the things we want to do. Furthermore, “taxpayer money” does not fund federal spending—it is new money spent into the economy providing a net-benefit for all, even for the rich (i.e. it is positive sum). And the delta between what is taxed and what is spent is new money added to the economy which is vital for growth. The government issues “debt” in the form of Treasury bonds to help mitigate that delta and constrain inflation, but this is not “borrowing” in the sense that you or I do it—it is the creation of new savings assets.

However, “genius” Musk is apparently too dumb, ignorant, or obstinate to understand these facts, which is why his cuts to the federal government have “saved” very little money, delivered no benefits whatsoever, and may have actually cost money in real terms. Cutting government spending shrinks the economy, it does not expand it; and much of government’s activity underpins economic growth, it does not restrict it. We’ve known this for years. The Kedrosky article misses this point, however, and seems to accept the “conventional wisdom” that we must cut spending for some arbitrary reason even as the fortunes of the super-rich grow exponentially.

Under this view, the US would, in a series of stop-start waves, cut spending and reform its obligations, aiming for what has been called the 3% target for deficits as a percentage of GDP. It will be wrenching, with the waves rippling back and forth from politics, to fiscal and monetary policy, and back to politics again.

The article also argues that a low-growth economy has cultural consequences as well. The pervasiveness of gambling in every walk of life, trying to make a killing, the rise of “hustle culture,” the lionization of entrepreneurs—these have long been parts of the capitalist mindset but they have become supercharged in recent years. This is because, when legitimate efforts like working hard and playing by the rules no longer offer any hope for a better future, all you can do is gamble and hope you end up as one of the few lucky “winners” rather than the rapidly expanding pool of “losers” in a zero-sum economy (my emphasis):

It should come as no surprise the rise on non-economic thinking predicated on lottery assets, like crypto. Unlike orthodox financial instruments, they don't represent a claim on productive output. They are, if anything, the negation of orthodox claims, a repudiation of the old way of doing things, pure price reflexivity.

This is understandable in a world where people have lost faith in economic growth. Why wait? Find things that go up and chase after them. We see this in the rise of crypto, of sports betting, of YOLO-ing meme stock-chasing Reddit bros, and more. What they have in common is impatience in the orthodox system ever working for them. And having lost faith in the system itself, institutional distrust becomes a baked-in feature of what they lust after.

You can think of them as a kind of ironic commentary on Life Under Two itself. Instruments are increasingly divorced from the system, acting almost as jokes in a surrealist play about what happens when nothing economic can happen anymore. They are what happens when money seeks returns divorced from economic foundations, turning inward on itself. We should expect even more of this kind of behavior...

This necessity of gambling in order to get ahead is also what’s behind the rise of house prices. Shelter—a basic human need—is turned into an asset commodity under capitalism, and the incentive for any asset is to make sure its price goes up in perpetuity and doesn’t ever fall. It’s also a tenet of neoliberal capitalism that people always follow “incentives.”

Seen from this perspective, rising house prices are exactly what one would expect to happen under this system, despite the “abundance liberals” attempts to blame exclusively “NIMBYs and zoning” and argue that people should somehow—just in this instance—voluntarily choose to act contrary to their own economic incentives. When work no longer pays, holding on to appreciating assets becomes the only viable route to prosperity, so people will do whatever it takes to make sure that asset continues to appreciate, even if it screws over everyone else.

Bizarrely, towards the end of the article Kedrosky seems to imply that AI could offer us a way out of this situation—a variant of the common “technology will save us” idea1. Indeed, AI has been seen by its proponents as a miracle technology (along with electric cars, batteries and solar panels) to usher in a new golden age of economic growth greater than ever before.

However, there is evidence that AI is making the world more zero-sum, not less. In fact, the job market for recent college graduates has been one of the worst ever seen, with unemployment much higher among recent grads than the economy as a whole. Even people in the media have started to take notice, and AI might be one of the culprits, along with economic uncertainty caused by recent events. Even “abundance liberal” Derek Thompson admits, “This really is a hard time to be a young person.”

And that brings us to two major points.

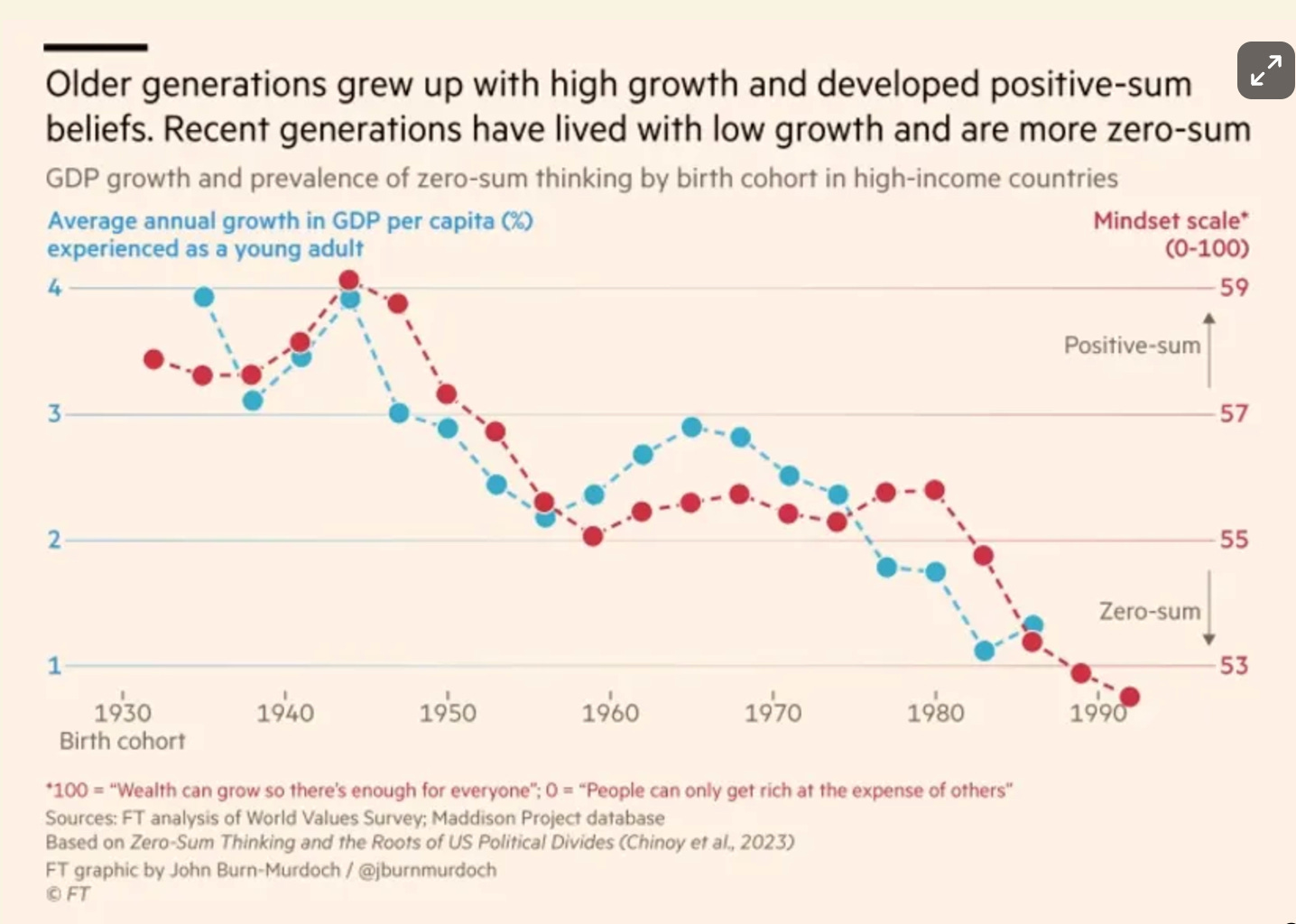

One is that this zero-sum view of the world is not confined to the United States. One of the major findings from recent studies is that generations who grew up under negative economic conditions and lower growth have a much more zero-sum view of the world than generations who grew up under more favorable economic conditions and higher growth (my emphasis):

Among the most striking Harvard findings was the discovery that there is a strong relationship between the extent to which someone is a zero-sum thinker, and the economic environment they grow up in.

If someone’s formative years were spent against a backdrop of abundance, growth and upward mobility, they tend to have a more positive-sum mindset, believing it is possible to grow the pie rather than just redistribute portions of it. People who grew up in tougher economic conditions tend to be more zero-sum and sceptical of the idea that hard work brings success. These attitudes are perfectly rational.

The pattern holds whether you look at people who grew up at the same time but in countries with varying economic fortunes, or different generations who grew up in the same places but against a shifting economic backdrop. Every five to 10 years, the World Values Survey asks people in dozens of countries where they would place themselves on a scale from the zero-sum belief that “people can only get rich at the expense of others”, to the positive-sum view that “wealth can grow so there’s enough for everyone”.

The average response among those in high-income countries has become 20 per cent more zero-sum over the last century. Moreover, two distinct rises in the prevalence of zero-sum attitudes have coincided with two slowdowns in gross domestic product growth, one in the 1970s and another in the past two decades.

Are we destined for a zero-sum future? (Financial Times)

According to this research, younger generations are significantly more zero-sum in their thinking than older generations. Is it so surprising, then, that are becoming more amenable to far-right ideologies?

One of the paper’s more stunning takeaways concerned the trait’s age-related patterns. “There’s a very stark figure in the paper that shows younger generations in the U.S. are significantly more zero-sum than older generations,” [paper author Stefanie] Stantcheva said… “If there’s been more growth, more mobility in the first 20 years of your life, we find it’s associated with being significantly less zero-sum,” Stantcheva summarized. “So in places like the U.S. or Continental Europe, where things used to be better in terms of mobility, the older generations are a lot less zero-sum.”

Why are we so divided? Zero-sum thinking is part of it. (Harvard Gazette)

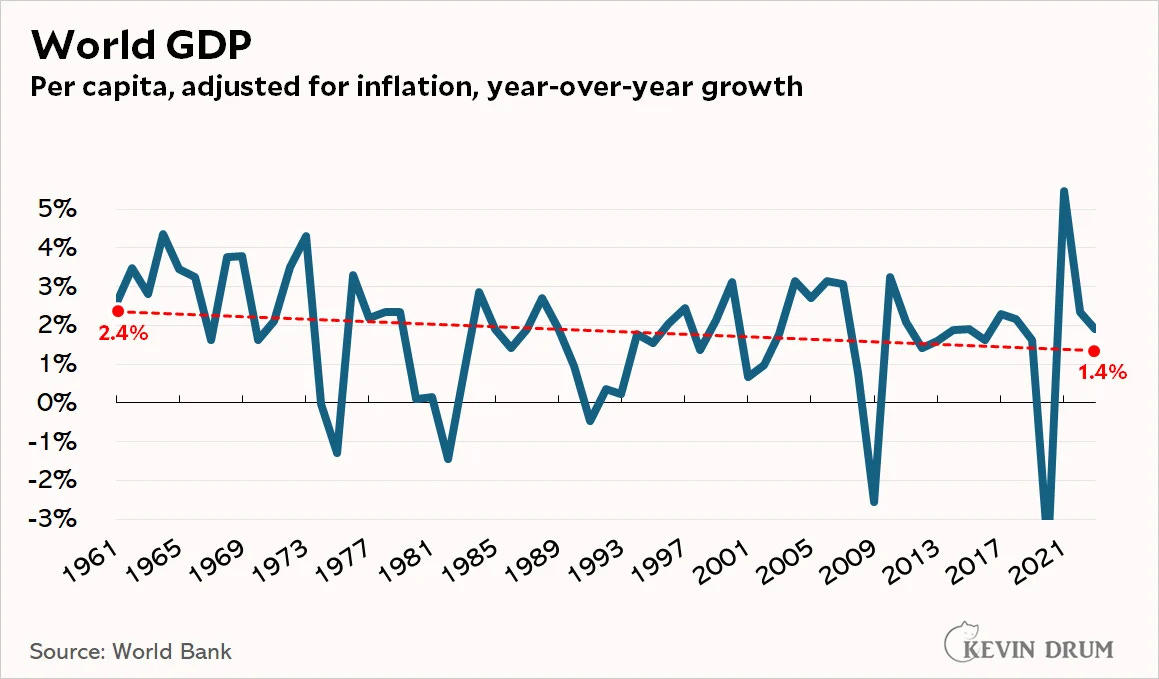

And the second point is that the slowdown in GDP growth is not confined to the United States, but appears to be the case for the entire world as the graph below illustrates:

The trend is clear: the whole world is slowing down.

What this means is that the scarcity mindset is increasingly dominating global politics which explains the rise of anti-immigration parties all over the world. Although Kedrosky’s post confines itself to the United States, all of the things he mentions are increasingly dominating politics in countries around the world, especially ones which had previously enjoyed abundant economic growth like Western Europe and parts of Asia. People’s attitudes are shaped by their relative status, not their absolute status, thus richer countries appear to be more vulnerable to far-right populism. For their part, populists are responding with carefully crafted messages stoking fear and resentment toward “others” as the source of all society’s problems.

What it also implies is that, if this is indeed the “new normal,” then successive generations will become ever-more zero-sum in their outlook going forward, which will pave the way for ever more repressive political movements and possibly a wholesale rejection of democracy and pluralism itself. It also means that, due to the dynamics of capitalism, absent renewed growth or a turn toward socialism, corporations will increasingly strip mine society to maintain their profits driving living standards down even further feeding the zero-sum mentality in a feedback loop.

In fact, there is evidence this is already happening. During the golden age of capitalism, stock market gains came almost exclusively from economic growth. But according to paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research, from 1989 to 2017, only 25% of gains came from economic growth, while 40% came from shifting wealth from workers to stockholders:

Why does the stock market rise and fall? From 1989 to 2017, the real per capita value of corporate equity increased at a 7.2% annual rate. We estimate that 40% of this increase was attributable to a reallocation of rewards to shareholders in a decelerating economy, primarily at the expense of labor compensation. Economic growth accounted for just 25% of the increase, followed by a lower risk price (21%) and lower interest rates (14%). The period 1952–88 experienced only one-third as much growth in market equity, but economic growth accounted for more than 100% of it.

Where do stock market returns come from? (Marginal Revolution)

But what is the reason we are seeing this slowdown in the first place? And can anything be done about it?

2.

And that brings me to the next column from someone calling themselves “The Honest Sorcerer:”

Back in the day, the Collapse subreddit on Reddit used to be a place you could go to find serious academic research and intelligent conversations regarding the future of society. Now it’s just a wasteland of random bad news along with toxic whining and complaining.

But back then, one topic of discussion was what might happen to society in the event of peak oil and how politics and society would change if the inability to increase energy inputs caused economic growth to falter or even decline.

The most sober and intelligent commenters back then knew that declining energy reserves would not cause the economy to suddenly collapse overnight as many of the more lurid and sensationalist (and popular) commenters argued. Instead, it would lead to a gradual slowdown in growth as the energy return on investment ratio relentlessly crept higher and higher2.

What that would mean was a world of permanently slower—or even nonexistent—growth. The discussions focused on whether this would cause a social regression as well once economic growth—simply assumed as a given under capitalism—started to slow down or even reverse.

Even back then, there were people with enough intelligence and foresight to predict what would most likely happen, and what they described was uncannily similar to what we are experiencing today; that is, what Paul Kedrosky described as Life Under Two in the previous article. Absent economic growth, they argued, we would revert to a zero-sum game where one individual or group could only gain at the expense of another. This would, in turn, make people increasingly mean, uncooperative, intolerant, vengeful, and violent.

This whole civilization was built around cheap fossil fuels, and after the Great Depression of the 1930’s: oil. With the slow agony of the oil age, and as global economic growth turns into stagnation then decline, the longest era of rising prosperity in human history comes to an end. Oil production has effectively hit a high plateau and failed to rise meaningfully over a decade now, even as world population grew by 10% during the same time period.

Considering the rise in energy demand of extracting petroleum over the past decade, this stagnation translated into a steep loss of oil products used per capita. Since the production of just about anything (from fish to solar panels) involves oil, the average world citizen has got poorer and poorer over the past decade. As for what to expect, hear out Dr Tim Morgan, former head of research at Tullett Prebon:

“If population numbers remain on their established trajectory of continuing (but decelerating) increase, this would leave the World’s average person some 34% poorer in 2050 than he or she is today. At the same time, this person’s real cost of necessities is likely to carry on rising at a rate of about 2.2% annually. Together, these trends imply that the affordability of discretionary (non-essential) products and services will contract by about 80% over the coming twenty-five years.”

Let that sink in.

The chart below seems to explain it all. We’re already flatlining. What happens when we move further to the right?

Based on this information, we know the following facts:

World GDP is declining.

Growth is slowing.

Oil production is peaking.

Zero-sum thinking is gaining in popularity worldwide, leading to the rise of the far-right.

Are all of these things related? The question back in the day was whether the end of growth would bring about major social and political upheaval. We appear to be seeing the exact type of politics that many predicted back then as the worst-case scenario: the recrudescence of zero-sum thinking and the scapegoating of vulnerable minorities as the solution.

There is a book written by political economist Benjamin Friedman called “The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth.” It’s a long book with a simple premise: Economic growth was essential for the moral gains the world has made over the past couple of centuries (e.g the end of slavery, women’s suffrage, less violence, increasing tolerance, democracy, etc.). But what happens when that growth goes away? And what happens if it goes away forever due to declining reserves of non-renewable energy that take millions of years to replenish? What if AI and batteries fail to magically reignite growth, or even make things worse? After all, AI cannot increase real resources—in fact, it actually consumes more resources, in some cases, vastly more.

Most historians attribute the Enlightenment to a sea change in intellectual attitudes with no further connection to underlying material conditions. In this view, it was just an inexplicable change that just happened to occur when and where it did with no deeper explanation. Many factors have been proposed for this like increasing literacy, but what if it was really expanding economies enabled by fossil fuels which allowed it to happen? For the first time since the dawn of agriculture, there were enough resources to go around for everybody, leading to more generous and tolerant social attitudes. But if that was the case, and if the economy stops growing, will see a return to a preindustrial or agrarian world-views in terms of social values; that is, a wholesale rollback of the Enlightenment? And are we witnessing the beginning of this already?3

What law is there that says the historical trajectory must be unidirectional?

In a recent post, Blair Fix made the case that fascist rhetoric is not actually new, but rather, old. That is, it is a reintroduction of the pre-Enlightenment world view back into modern political discourse (my emphasis):

Gazing at the totality of our linguistic evidence, one thing seems clear: fascism is overwhelmingly an ideology of the past. It is a modern label for a collection of dark ideas that have long plagued humanity. People believe in the ideals of humanism and the Enlightenment to the extent that this ideology delivers real benefits. And for several centuries, it did deliver the goods, obviously because rationality and evidence are a great way to solve problems. But lately, many anglophones have been losing faith in science, reason, and evidence, turning instead to darker ideas from the past.

For their part, scientists have noticed. For example, in 2018, linguist Steven Pinker felt compelled to devote a whole book to defending the ideals of the Enlightenment. It’s an enjoyable tome, filled with erudite philosophy and a plethora of evidence. But it’s also fundamentally condescending—a prime example of elite deafness. Pinker bends over backwards to demonstrate that today, life is good—that people have no reason to be angry. But wouldn’t the enlightened approach be to assume that folks do have a reason for turning to dark ideas…that for many people, life is not good?

Here, Pinker’s dismissal of inequality is an ironic example of dis-enlightenment among anglophone elites. Only in the lofty seclusion of the ivory tower could you pretend that the unfolding descent into oligarchy is unrelated to the rising tide of fascist rage. To say that nothing is wrong borders on satire. Neo-fascism is here, it is real, and it is terrifying. In other words, something has gone horribly wrong in anglophone society. Perhaps we should admit that so we can start looking for solutions.

The Deep Roots of Fascist Thought (Economics from the Top Down)

It is notable that the initial rise of fascism occurred during a long period of zero growth and stagnation in the aftermath of World War One and the Great Depression4. Are the correlations made by Kedrosky above between slower economic growth and social and political attitudes in America (and recall that the far-right is gaining in popularity worldwide) merely a coincidence?

If these assumptions are correct, it could lead to every individual and group fighting tooth and-nail for their share of a shrinking pie—in other words, a Hobbesian “war of all against all.” We’re already seeing this in the zero-sum world view promulgated by vulgar populists like Donald Trump and others in order to acquire tyrannical power. If this is correct, we’ll likely see these ideas spread and only become more popular and more virulent as time goes on.

Is there any hope? Well, if population shrank in line with resources, it would be much, much easier to deal with slower growth in an enlightened, humane manner. And if we adopted a more compassionate, sharing attitude, making the best use of our (still relatively abundant) collective resources in order to benefit everyone, that would help, too. Note that European countries with greater equality and better social services have proven more resilient to the lure of fascism than places like Russia and the United States (although even they are not immune).

But the problem is that this is called socialism. Socialism plays on the best instincts of our nature, not the basest instincts as does fascism, and therefore has a much worse track record of success. Note that the current elites and their allies in the media are working mightily to repress burgeoning socialism wherever it occurs and trying to prevent the population from shrinking. Also note that both efforts are in line with fascist ideology, hence the idea that “fascism is capitalism in decay.” When capitalism falters, it is fascism—not socialism—that is the elites’ preferred alternative.

If that’s the case, then the choice really is between socialism or barbarism. Which will we choose? So far, it’s not looking good...

A close cousin of “They”will think of something.

From the “Honest Sorcerer” article: “…a century ago less than 5% of the energy of a barrel of oil had to be reinvested into exploration and drilling…we now have to spend over 15% of the hard earned energy from crude on getting the next barrel. This ever growing energy demand per barrel retrieved has no upper limit and can be expected to increase to as high as 50% by the middle of this century.”

Consider the rising popularity of “Dark Enlightenment” thought, which unapologetically calls for an end to representative democracy, a restoration of monarchy, and the return of repressive social and political structures as a means of control based on a “law of the jungle” view of society. These ideas are very popular among MAGA and Silicon Valley.

Note, also, that neoliberalism was introduced once the golden age of capitalism from 1945-1973 came to an end. This was also accompanied by stagnation and an oil shock. Another step down the ladder.

The end of growth, Peak Oil/energy and similar themes have been talked about since 2008 at least, but none of the major predictions or effects have come to pass. At least in the USA, economic growth continues, unemployment remains low, and gas prices are cheap.

The chart of world GDP is interpreted selectively. Yes if you start in the 60s and squint then you can see a declining trend; but start the graphic from 1975-77 and there is no trend at all, no apparent decline in average per capita growth over this 60 year period.

What is certainly true is that over the past 40 years, the *gains* from growth, efficiency improvements through automation and trade, etc. have been disproportionately captured by the 1%, which is very different from asserting that growth has ended or that resources are becoming absolutely scarce.

Why the American political system has been unable to address such inequality is a very complex question. I would list many factors including the two-party system, the Senate filibuster, campaign contributions and donations by the rich, dominance of the party infrastructures and think tanks/academia by the well-off 1% winners, and the culture wars which have sucked all the oxygen out of the room. You are also never going to replicate the Nordic social model in a huge continent-sized country of 330 million with vast and growing ethno-linguistic and cultural divisions.

https://www.hamptonthink.org/read/the-end-of-an-empire-systemic-decay-and-the-economic-foundation-of-american-fascism