Read Part One

Last time we saw that humans were able to take control of their ecological niche, altering it though artificial means and redistributing more of the earth's net primary productivity to themselves while depriving it from other parts of the plant and animal kingdoms (causing extinctions and ecological degradation which persists to this day). People began eating lower down the food chain. We altered our primeval niche but never adjusted our breeding strategy accordingly.

The effects of crowding led to the establishment of governments and occupational specialization. These were partitioned into broad and narrow niches, with the people at the top of the hierarchy occupying the broad niches and the rest occupying the narrower ones. Those in the broad niches were able to live in much the same way as their Ice Age ancestors. Meanwhile people in the narrow niches lived much more constricted lives than their ancestors. We use the terms wealth and poverty to describe this phenomenon. Assortative mating, where rich people exclusively marry other rich people, also contributed to this trend.

Our primeval niche is the most desirable one to live in, but there are only enough resources for a few people to live that way so there is constant competition for those spots. Yet, just like niches in nature, the size of the niche is always smaller than the number of people who want to make a living it. In nature, this leads to culling; in humans, it leads to conflict. Because the people who occupy the broad niches use the most resources per capita, they opt for smaller families. In addition, the pressure from rising numbers and resource shortages are felt in the broad niches first because their lifestyle requires the most resources to sustain.

Because the effects of crowding are felt more keenly in the ranks of the broader niches first, political revolutions tend to come from the ranks of the upwardly-mobile middle classes rather than the downtrodden masses. Disruptions of the social order are rarely instigated by the peasant classes who are accustomed to living in a narrow niche.

The American rebellion was led by a landowning elite. The French Revolution was fomented by a literate, upwardly-mobile bourgeois class that was effectively shut out of power, many of them jurists. The Taiping rebellion was instigated by someone from a well-to-do family. Many Marxist Revolutionaries were educated intellectuals and trained professionals.

Middle and upper-class niches are inventions. They are developments of our original trick of changing the primeval niche through agriculture and settlement. When new niches are first invented, few people live in them; an ecologist would say the niches are "empty." We should expect, therefore, that many generations must pass before life in these new niches could be crowded. It must follow, then, that the social unrest, which is the prime indicator of crowding in these better niches, will always be long in coming.

Lulls of social peace occur, particularly as a small inventive state begins the process of growth. Social unrest follows, always as a distinct episode. This is why revolutions are revolutionary, a sudden upset of the old ways, as in France and Russia, or the upheaval of 1848 when kingdoms collapsed all over Europe. These events all followed technical change and rapid population growth, but were decades in the making. (p.78)

When those in power must lose privilege because the numbers of their own kind rise, social unrest must follow. Social unrest, therefore, is a necessary consequence of changing the niche without changing the breeding strategy. Furthermore, the unrest will be a middle-class phenomenon and probably episodic. The troubles come from trying to pack in a few more of the relatively wealthy, not from packing in many more of the relatively poor.

I suggest it is axiomatic of human history that social upheavals, even revolutions, do not emerge from the ranks of the poor...They come from disaffected individuals of the middle classes, the people who experience real ecological crowding and who must compete for the right to live better than the masses...The episodic quality of these revolutions comes about because scattered disaffection alone may have little result. Individuals can wage a brief struggle for the niche of their parents, then accept defeat and sink to a narrower vocation in life. (pp. 76-77)

One way to cope with the surfeit of claimants to the upper-class niches is the establishment of some sort of caste system in which access to the higher niches is limited by social convention, thus tamping down competition and social conflict. This could be blood relations, or it could by something else such as wealth or ability. Colinvaux speculates that the extraordinary stability of certain Asian societies was due to long-standing caste systems: "It was the stability of neither change nor opportunity." (p. 83). Sometimes caste system are hidden rather than overt, such as the accelerating demands for expensive education in the United States and the determinism of one’s ZIP Code making class mobility practically impossible.

Niche theory deals a blow to the American notion of "upward mobility" as the solution for poverty, since there are only so many slots at the top. And for everyone potentially moving up the hierarchy, someone else must be moving down, unless living standards rise across the board. All it really does is increase competition, decrease social cohesion, and place the blame entirely on the individual.

Castes have been described from many ancient societies—Egypt, Greece, Rome, Persia, Fiji as well as India and Europe of past centuries. Castes are apparently ubiquitous. They ration resources among the populace when broad niches are not attainable by all. They raise and educate an individual to one of the many niches of society. (p. 84)

Caste systems must largely fail before universal education, which, at least in part, trains people to choose from a variety or vocations for which they might be prepared. But education does not remove the need for constraint; if caste no longer works to choose a niche, some other constraint has to be invented.

In a market economy, the individual is allocated a niche by economic circumstance. In a socialist state the individual is allocated a niche by a government official. But people are still sent to a way of life that has to be, for most of them, less than the best. It is always crowded around the broader niches, and the more dense the population, the more crowded it will be. The defenders of a high way of life must push against the competition. Social oppression is an inevitable consequence of the continued rise of population. (pp. 84-85)

Colinvaux notes that, in general, societies with low population density tend to have more freedom. These societies tend to enshrine freedom and liberty as their highest ideals. This is because the most desirable niches are less crowded so there is more social mobility. Think of the low-density barbarian societies surrounding ancient Rome compared to the highly-stratified Roman society with its extreme wealth differentials. In fact, ancient Roman writers wrote admiringly of the rugged independence, ferociousness and courage of the Celtic and Germanic barbarians they encountered, contrasting it with the values of their own "decadent" society of extreme rich and poor. The American idea of "freedom" developed during the frontier days when the continent was mostly "empty." Those outdated notions are running up against the stark reality of a continent (and a world) that has been filled up leading to increasingly disastrous results.

Societies that talk a good game about freedom and liberty have always been those where there were plenty of spots available in the broad niches to accommodate aspirants to them. These tended to be growing, expanding societies, with plentiful resources and low population density. But crowding inevitably invites repression as the people occupying upper niches try to limit claimants to their positions (in other words, pulling up the ladder after them). As the effects of crowding become more and more acute, however, governmental authorities begin to impose ever more restrictions on behavior. This gradually leads to a political repression and the policing necessary to accomplish it. Freedom and liberty go by the wayside and democracy withers away, even though it is still paid lip service.

Crowding in the upper ranks must produce a response in the government of society. We can expect that the descendants of those who once labored for the poor might well become inward looking, concerned only with the defense of their own privilege. Like poverty itself, a gradually repressive ruling class must be the inevitable consequence of indefinite population growth. (p.79)

This leads to the first broad strokes of Colinvaux's ecological theory of history:

After the original inventions of wealth and poverty, therefore, niche theory predicts:

That middle and upper classes will be the first to feel the pressures of crowding.

That ruling classes which previously were sympathetic to the mass will become selfish and oppressive.

That social troubles will be episodic rather than continuous.

That methods of allocating people to the more narrow niches will evolve. Caste systems are the most [humane] of these methods, but capitalist economies and socialism have their equivalents.

That even under oppression, population will be stable only if the optimum family for the most miserable class is less than the needs of replacement. (p. 85)

The other alternative is to expand space in the broad niches to accommodate the lower class aspirants and assuage social conflict. There are three common ways to accomplish this. Colinvaux describes them as trade, colonization, and war.

When you run out of niche-space for the good life, you can always look for more somewhere else—through trade, through colonies and through aggressive war. We think of trade as "good," colonies and conquest as "not so good." Yet all three serve to tap the resources of other people's land. And they all need military hardware for success. (p. 85)

When societies come into conflict with one another, the winner is always the society with the superior military technique. Colinvaux cites numerous examples throughout history, from Egyptian war chariots, to the Macedonian phalanx, the Roman legion, the Iranian heavy cavalry, the steppe horse archer, the English longbow, the French massed infantry, to the Panzer divisions of World War Two and finally nuclear weapons. According to Colinvaux, the victorious society is always the one with the superior military technique.

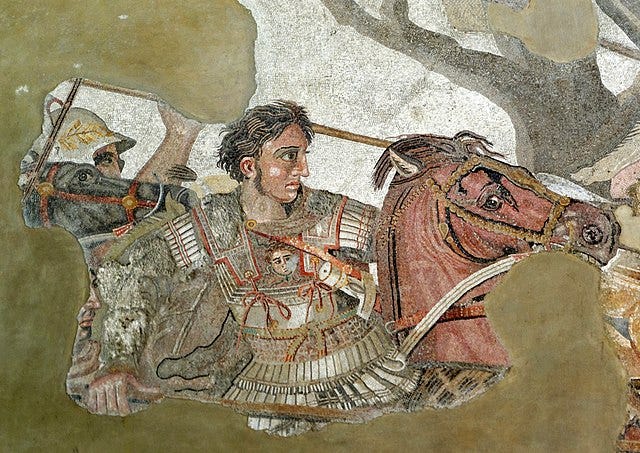

Where do these techniques come from? Conflict zones are the crucibles for the development of such techniques. A great portion of the middle part of the book is given over to military history to elaborate this point, and these vivid depictions of military history are worth reading in their own right. Colinvaux argues that the conquests of Alexander the Great were fueled by military techniques forged in the "snakepit" of ancient Greece where numerous city-states fought constantly over a limited portion of arable land on the rocky Greek peninsula. Furthermore, Greek colonization and trade led to the development of a superior naval fleet and sailors which also increased military advantage relative to their neighbors.

This is what allowed Alexander the Great to consistently defeat his enemies in battle. That Alexander was a brilliant military strategist was secondary to the fact that he had the superior military technique. Alexander's conquests are an example of a growing society expanding outward taking land from its surrounding neighbors to acquire more niche space. Alexander and his generals set themselves up at the apex of the new social order, and Greek culture dominated this part of the world for centuries.

Colonization is another means of expanding niche space. The parent society sends out colonists to form daughter societies. Often territory is acquired from colonized peoples by force. The colonizers can do this because they have developed the superior military technique in the crowded conditions of their parent societies. They have also developed more efficient farming methods that allow them to support more people at higher population densities.

Again, the ancient Greeks provide a textbook example as they fanned out across the Mediterranean Sea establishing colonies such those in Sicily. The Phoenicians are another example, using trade to create new niches for their people around the Mediterranean region, founding colonies such as Carthage on the coast of North Africa along the way. Colonization and military conquest are on a continuum of seizing niche space from others:

True colonies represent the simplest form of land theft. You send out soldiers, occupy a piece of land and fill it with settlers. You carry on your own expanded way of life away from the parent city, not so much relieving congestion at home as providing the necessary opportunity for the increased numbers in each generation.

When you have many colonies, you might fill in the gaps between and make a small nation-state. All colonization is aggression, but there is a gradient from making a small settlement to wholesale annexation of aggressive war. You use your superior weapons to take niche-space from others, by force. (p. 90)

The conflict between Rome and Carthage is illustrative. Rome came into conflict with the neighboring tribes of the Italian peninsula. Over centuries of warfare, they developed the superior military technique: the Roman legion. Carthage, by contrast, was unable to expand into the interior of Africa due to geography. As a result of this limitation they terraced the hills around the city and practiced an intensive, highly productive agriculture, along with turning to the sea to trade with neighbors and establish colonies. This caused them to develop into a formidable naval power. The conflict between these two approaches led to the Punic Wars for dominance of the Mediterranean:

Roman authors, and our school books, tell the tale of these wars as a struggle to see which state should be mistress of the world; Rome, with all Italy already in its power, or the trading city of Carthage, sweeping the Mediterranean Sea with merchants and fleets. Rome did indeed go on to conquer and enslave every nation within reach of its terrible legions. But the war was not over who should be "mistress." It was a struggle for raw survival by the civilized folk of a trading state against the resources and weapons of a continental power. I suggest that the good guys lost. (pp. 135-137)

Colinvaux's insights on trade are interesting, especially given its prominence in modern economic "science." According to him, trading regimes initially develop not to supply necessities to the parent country, but from a desire of the middle and upper-middle classes to expand their niche space. Those who are frustrated by the lack of niche space within their own societies look outward to buccaneering trade to provide sufficient lifestyles for themselves and their children by tapping the resources of distant lands. Aggressive, ambitious, unscrupulous individuals who find their ambitions thwarted at home often turn to adventurous trade to create new high-status niches and have done so throughout history: "Trade is the simplest of the three ways to expand. You say where you are and fetch objects you want in ships." (p.85)

Trading regimes expand niche space not just for the traders themselves but also for people in the home country as well. People at home are given jobs in order to manufacture the articles required for for trade. New positions are created marketing and distributing the imported goods. Trading societies are thus expansionist, which leads to higher living standards and population growth. This desire for expanded niche space contradicts the "free and equal voluntary exchange" theories offered by economists which was rarely the case in actual history:

Our historians talk with approval of the "merchant adventurers," the people who sought a broader way of life through trade. For trade to work, there must be a market for imported commodities, but this market will result from the very increase in population which drives the better-off to trade.

The way must always be open, therefore, for sons of the wealthy to find lives of freedom in importing objects that the masses want. We expect trade to develop not in the service of the hungry poor, but in the service of the aspiring middle class. The ecological hypothesis predicts trade to be important in a state only when there are too many people trained to better-class ways. But trade must also have an immediate effect on the opportunities open to all classes, because the parent society has to make the objects to be spent in trade.

In creating niche-space (jobs) for children of the wealthy, trade must also create jobs (niche-space) in the parent state. Because people must make things to sell outside, trade multiplies the niche-spaces available in the crowding state. First people can find a broad-niche life by engaging in trade, then other niche-spaces are made at home for those who supply the articles of trade. But even the stay-at-homes are getting part of their living from other people's land. It is quite wrong to think of those who stay at home as being supported by the homeland, because many dimensions of their niches are supplied by the foreign states who take their manufactures. (p. 86)

Whenever expansionist trade did develop it was usually aspiring middle-class individuals denied places in the upper echelons who were at the vanguard. In Italy, Spain, Portugal, England and the Dutch Republic, it was wealthy upper class individuals (the bourgeoisie)—not the peasants—who established trading regimes. In Europe, due to primogeniture there were many younger sons of the aristocracy who were shut of out of inheritance who fueled both expansionist war (the Crusades) and trade (The Age of Exploration). Under capitalism the traders have become, in effect, the ruling class, occupying the broadest niches.

As trade grows, living standards increase for all—both the traders and the beneficiaries back home. This causes population growth, forcing countries to become dependent upon trade in order to feed their growing populations. But—and this is important—growing populations are a consequence of successful trade, not a cause of it. Again, this seems counterintuitive:

After trade becomes commonplace, the hypothesis predicts a second and inevitable consequence: the mass of the people will become dependent on imports for their very subsistence, very likely even for their food. They do this because their numbers go on rising after trade has become important to the state, as well as before. This late-arriving portion of the population is dependent on imports for necessities. Once, therefore, a state begins seriously to trade, the rising numbers that trade makes possible become dependent on continuing the trade.

This analysis departs drastically from conventional wisdom about trade. We usually think of trading states, say modern England or Japan, as being driven to trade in order to feed their people. Modern politicians in those countries make speeches about "having to export in order to live," which leads people to think that the dense populations came first, and that some desperate necessity drove the crowded masses to resort to foreign commerce. But the ecological analysis denies this. The crowded masses are not a cause of trade, but a consequence of it.

The only way in which crowding causes trade is through the pressure on the lives of the better off. Children of wealthy people engage in adventurous commerce to maintain their own standards of life. By doing so, they make it possible for more people to be raised in subsequent generations. These new people are the ones who are physically crowded. They are dependent on commerce, certainly, but they only appears as a result of the commerce started by others. (p. 87)

Colinvaux's other insight about trade is that trading regimes must necessarily develop into military powers. This is because long-distance trade is inherently dangerous: you are moving large amounts of goods through hostile territories where they can easily be seized by hostile governments or pirates. To counteract this, military techniques must be developed that are not only capable of projecting force, but also sacrificing as few soldiers as possible since you are typically outnumbered and not fighting on home turf. This leads to the development of powerful weapons and military techniques by trading regimes. We see this throughout history—from the Phoenicians, to the Greek and Carthaginian navies, to the Venetian Arsenal, to Islamic merchants, to the Spanish and Portuguese galleons, to the British Empire which ruled a quarter of the earth's surface at one point. These thasallocracies all developed superior weapons and military techniques that allowed them to dominate much larger populations with a relatively small amount of troops, and their empires all began as trading regimes.

A civilized soldier employed by the merchants will be armored, for he fights not out of pleasure but from calculated necessity. Getting hurt is to be avoided. Weapons, tactics and discipline will reflect the organized life of his thriving city. The hypothesis predicts, therefore, that an emerging trading state will develop the best weapons and armor that their technology can produce; the city will take, as it were, a cost-effective attitude to the arts of war. (pp. 88-89)

Colinvaux's insights on trade, then, can be summarized by the next predictions of his ecological hypothesis:

We can add to the list of predictions of the ecological hypothesis:

That trade will develop as the niche-space of middle and upper classes becomes crowded.

That opportunities in manufacture increase as trade grows.

That the population rises and grows denser as a consequence of trade.

That the trading state acquires advanced weapons and an army. (p. 89)

As Roman society grew and prospered after the Carthaginian wars, this led to rising numbers, and rising numbers led to an emptying out of the countryside. This example leads to another of Colinvaux's key insights: population growth will lead to an emptying out of the countryside and a crowding of people into cities. Again, this may seen counterintuitive: "Surely we need more food producers out on the land to produce enough to feed all the hungry mouths in the cities," is what you might be thinking.

Not so, says Colinvaux. Rather, the highly intensive food production techniques required to feed the urban masses means that less and less people are employed in agriculture over time. These displaced farmers crowded into the cities where they became a restless urban proletariat.

In ancient Rome, for example, large-scale plantations worked by slaves producing cash crops for export led to greater surpluses (and more market-based trade) than the family-owned subsistence plots of a generation earlier. A concentration of wealth allowed smaller farms to be bought out by larger ones, reducing niche space for small farmers. As their niche shrank, farmers headed to the cities to look for other work becoming merchants, artisans, shopkeepers, soldiers, or simply malcontents.

It is also far easier for governments to house and feed centralized populations than decentralized ones scattered across the countryside. That is why there is an impetus for cities to expand in size and population as a society becomes more prosperous. In Rome, for example, the Cura Annonae shipped directly from Egypt is what kept the urban masses alive (and hence unrest under control). Note that this policy was instigated by the upper classes.

This emptying out of the countryside was remarked upon by numerous writers in antiquity. Colinvaux argues that these writers looked upon the empty countryside and abandoned small farms and mistakenly concluded that this was a sign of population decline, when in reality it was a sign of population increase.

The United States is a clear modern example. Even as rural communities across the country have emptied out and become dilapidated ghost towns, the overall population of the country has consistently grown. The U.S. is world’s third largest country by population. And this is happening worldwide—as populations expand, cities metastasize to accommodate the teeming masses of urban poor. Half of the world's population is expected to live in cities by 2050, with overall population continuing to increase throughout this period.

...There is a drift from the land as peasants are displaced in the interests of increased production. This happened in ancient Greece and Rome no less than in the time of the enclosures in Tudor England, or in modern industrial states. The process can be seen in the development of every civilization. Feeding great numbers of people is more easily done if they are brought together in dense settlements; running the agriculture needed to supply those dense settlements is more efficient in the larger agricultural units of agribusiness.

And the "drift from the land" is a predictable consequence of a dense population growing denser. It follows, therefore, that partial depopulation of the countryside results from population growth: the land [loses] people even as the total population climbs. It is easy to mistake this loss of people from the country districts as evidence of a population fall. Roman Pliny made this mistake and there are historians who have followed his errors to this day. But emptying of country districts must be a usual consequence of a population rise, not of a fall. The modern United States of America is an example.

In actual human practice, the first-order reason for driving peasants from the land was to enrich the landlords, but societies put up with the miserable injustice involved because the new ways were more productive; letting the landlords have their way yielded more food for the state, and if pushing even more people into the growing populations of the towns' displaced peasants, it at least promised bread for those growing populations. This is the argument of our "green revolution," an argument that has been used as long as there have been civilized states. "The people must be fed; farm the land efficiently for the benefit of dense settlements."(pp. 100-101)

A final strategy after oppression, caste systems, colonization and foreign trade, is simply seizing the lands of your neighbors through force. Colinvaux uses the examples of Alexander the Great and the expansion of ancient Rome. In one case, the society with the superior military technique expanded by taking space from older, more established cultures. In the other, the society expanded into areas with lower population density (Europe north of the Alps), seizing and exploiting new resources in the process.

When numbers and aspirations for broad niches continue to grow beyond what can be accommodated by trade, then the only expedient left is outright theft. A growing city-state will certainly find itself in a world peopled by others less citified and less densely populated. Very likely much land will be full of wandering herdspeople or nomadic farmers, ways of life that do not support dense populations.

It may even happen that citified people will find lands still occupied by hunter gatherers, as when Europe first thrust itself into North America. More often the surrounding lands will be inhabited by people whose ways of life the city folk had left behind them some generations before. What is certain, however, is that the neighboring land is, by the standards of the city, underused and undersettled. The city-state will be surrounded by cultures whose technology of extracting niche-space from the land is inferior to its own. Taking over this land is an obvious thing to do.

The ecological hypothesis predicts, therefore, that a society will engage in land theft when its organization and aspirations show it to be better able to extract a living from the surrounding lands than the people already there. And it follows that a society which has reached this position also has, and knows it has, the better weapons.

Land theft means planting a colony or annexing a whole territory. Both processes must be resisted by the people already there. But those of the civilization who covet the land have an advanced technology of war, inevitably, by reason of the technology and trade which has made them a city. When they begin armed emigrations, whether for colonies or for empire, they cannot be stopped. This is why nations like Rome or Greece built such glittering victories. (PP. 89-90)

This tactic is also likely to be self-defeating, since eventually the cost of expansion leads to diminishing returns the farther people expand outward from their homeland. This may be because of technological limitations or by running up against inhospitable environments or hostile natives. Also, what often happens is that the neighboring peoples adopt the military weapons and techniques of their opponents, leading to a bloody stalemate as the aggressor society no longer has the upper hand militarily. Colinvaux cites the example of the Roman empire versus the Germanic barbarians and Sassanian Persians.

The Persians were the first to deploy heavily-armored cavalry for use in warfare. They were also early adopters of horse-mounted archers who were able to fire while retreating (the "Parthian shot"). The Eastern Roman Empire adopted the Persian heavy cavalry techniques as the Byzantine cataphract, allowing it to hold onto its territory. Eventually the cataphract was adopted by the barbarian Goths who used it to defeat the Eastern Romans at Adrianople. The use of heavy cavalry subsequently spread throughout the barbarian tribes and became the basis for the medieval knight—heavily armored mounted soldiers who dominated warfare until the adoption of gunpowder.

Eventually, the barbarian hordes who seized North Africa from the crumbling Roman Empire were overrun by another outsider group—the newly united tribes of Arabia under the banner of Islam. These mounted horsemen, accustomed to the techniques of banditry and raiding, swept out of the desert conquering everything in their path until they met the armored knights of Charles the Hammer in France and the Byzantine cataphracts of Leo in Turkey. These societies all expanded until they met others who had equal or superior military techniques to their own, whether invented or adopted. Fundamentally, all of these expansions were driven by growing populations looking for additional niche space:

When the leading classes of a state have led their people through the stages of technical improvement in manufacture, a class hierarchy, trade and the colonial expropriation of land, they are coming to the end of the possibilities for finding more niche-spaces. Yet a society putting all these into effect is likely to be a buoyant one and its people are likely to be conditioned to the long success story. The breeding strategy, therefore, will certainly work to keep families relatively large. Each couple of the colonial state will choose its family in some hope, and this will be so in both parent city and daughter colony. This means that the succeeding generations will see more people still, not just starving poor but more particularly aspiring upper castes and classes.

All that can now be done by the rulers to keep control is more of what has gone before, and this we must expect: more attempts at trade, more social ranking, more aggression. Aggression seems the most promising alternative.

Sending out a civilized army to take yet more undeveloped land is not only likely to succeed, but also exciting. And so niche theory suggests that a tide of aggression ought to flow out of the expanding state until a time comes when something stops the flood of armies; perhaps the distance of communications, perhaps reaching a boundary defended by some other army of almost comparable technique, perhaps a combination of both.

Aggression remains available as a solution to crowding in the more desirable niches only for as long as the weapons of the state are superior to the weapons of any people within reach. The aggressor state will always be both wealthy and wanting more wealth. Victory will always be achieved through superior technique...

We will find a similar pattern of events behind all the greater conquests of history. Aggressive conquest is to be expected whenever population and aspirations grow together. Up to now every advance of civilization has been accompanied by rising desires and rising numbers. Always this has resulted in aggressive war. Ecology's second social law may be written ''Aggressive war is caused by the continued growth of population in a relatively rich society." (PP. 91-93)

Aggressive war becomes a habit to nations that pursue it successfully. But within these victories lie the seeds of decay. The options are running out. Once the society is at its height, with plentiful niche space, the only thing that is left is decline. New powers are on the horizon, and they have copied the techniques of the more successful societies and perhaps even improved on them.

Expanding societies eventually become sclerotic which leads to social conflict and decay. In the end, the Roman empire turned to incessant fighting and civil wars as disaffected elites battled it out among each other for niche space at the very top, while the newcomer barbarians occupying the narrow niches of society—who required fewer resources than the native-born Romans—outbred them even while selectively adopting elements of Roman culture. The empire was overrun by less dense, less sophisticated powers from outside as it lost a sense of shared common purpose. Eventually, population did indeed fall, but only as the empire was already decaying and in terminal decline.

Yet at the very top of the social heap it is possible that a few families were small enough to be below the replacement rate. An intriguing suggestion of this lies in the fact that none of the Antonine emperors had sons to succeed them except the last. This was a very fortunate circumstance for Rome, because these men then adopted sons to be their successors, choosing boys for their quality to be emperors themselves one day. It was probably this circumstance that gave Rome its precious hundred years of stable government in Antonine time. The good years ended when the wise Marcus Aurelius most unwisely left the Empire in the custody of a real but quite unfitted son, Commodus. (p. 163)

Colinvaux dismisses the "spiritual/biological” theories of history which argue that a society goes into decline either because it has a fixed lifespan just like an individual does, or because of a sort of moral malaise, or because of a failure to rise to certain challenges. He compares his ecological theory of history against Toynbee's massive work, A Study of History. He finds that it explains the observed historical patterns much better than Toynbee's own theories about spiritual decay which Colinvaux views as quasi-mystical not based on hard science. Rather, he says, it is the growth of population and an exhaustion of options for expanding niche space that leads to social unrest and ultimately, collapse, once the various options for expanding niche space have been exhausted:

The combined expedients of better government, better technique, emigration and going to war can, of course, never produce more than a temporary relief from the pressures of demand. If numbers go on rising, the condition of the people, both leaders and led, will be as constrained as ever within a few generations at most. However large the empire built from underdeveloped lands, there has always been a finite limit set by logistics and geography. When all is full there is nowhere else to go.

Niche theory predicts, therefore, that a limit will be reached to the number of broader niches that can be found by ingenuity, trade and theft. And yet, the theory also predicts that the numbers desiring broad niches will continue to increase. The empire will become crowded for its upper classes. It is this phenomenon which is likely to be the cause of decay. Social unrest is now inevitable.

As the empire crowds, freedom of choice must be an early casualty. There has to be more government to allocate and control. Bureaucracy will be getting more complex, its practitioners more numerous. This is so inevitable a consequence of expansion that a minor ecological social law might be written, "All expansion causes bureaucracy."

But the bureaucrats cannot make more resources, they can only allocate what they have. Opportunity for betterment wanes, and initiative must wane with it. The army is no longer the pathway to a good life and will be neglected. After all, the only role soldiers have left is defense against distant barbarians. Once a fresh military power appears at the borders the empire must fall.

In the final days the empire may linger on if it can impose so stern a caste system that many families are held small by want. This is what some of the longer lasting civilizations such as Byzantium and India achieved. But this works only until other states catch up with the static weaponry of the moribund empire. Then comes destruction.

The final set of Colinvaux’s predictions can be summarized, then, as:

Superior weapons will be used to expropriate land and to plant colonies.

All aggressive enterprises are undertaken with superior military technique and in a calculated manner.

Aggressive wars are launched by rich societies and come from the needs of the comparatively wealthy, not of the poor.

An elaborate bureaucracy and loss of freedom will always appear some generations after the establishment of empire by conquest.

Collapsing empires will have rigid caste hierarchies and stagnant military techniques. (PP. 93-94)

After outlining his ecological theory of history and making the comparisons with Toynbee, the central portion of the book is dedicated to applying his ecological hypothesis to various episodes in world history.

The most extensive of these is what Colinvaux calls the "Mediterranean episode." He describes this period as approximately from the flourishing of Greek civilization and the conquests of Alexander the Great, through the rise of Rome and the Punic wars, through the collapse of the Roman Empire and the partitioning of its former lands between the Christian barbarian kingdoms, the Islamic caliphates, and the Eastern Roman empire.

One of his more interesting takes explains the periodic expansions of nomadic steppe peoples. These societies have repeatedly overrun neighboring agrarian civilizations since the dawn of history. Colinvaux suggests that these periodic waves are driven by weather fluctuations on the steppe. During good times, people's breeding strategy remains unchanged so the population expands. But when the weather takes a turn for the worse, there are not enough resources on the steppe to support the number of people living there. This drives them to expand outward and seize the stockpiled wealth and resources of their sedentary neighbors. The lifestyle on the steppe, based on raiding and fast attack, gives them the superior military technique. This, he says, is what drove the periodic nomadic invasions we see throughout history. The analogy he makes is between the human breeding strategy and that of the steppe-dwelling rodents known as lemmings:

Population cycles of steppe-people as well as of lemmings are…synchronized by weather, although they are definitely not caused by cycles in climate. Both lemmings and people use weather as cues for behavior, the lemmings for simple sex, the people more subtly. All people behave to suit the weather but pastoral nomads are more closely tied to weather than the rest of us so that small changes in habit bring large consequences in population.

Yet the climatic pattern of good years and bad is purely random, for both people and lemmings. The length of time between one population high and the next is, for both species, set by how fast each can breed, how long each lives, and how prompt each is to respond to changes in the weather. Lemmings can raise a baby in six weeks, live a year, and produce huge populations at roughly four-year intervals. People take twenty years to raise a baby, live sixty years, and produce largish populations roughly every five hundred years. The cycles are thus properties of the animals, not of climate...

In this way the whole steppe would start filling with too many people, synchronously, because habit was triggered by weather just as the tundra of large areas can fill with lemmings. People grow and reproduce more slowly than lemmings, and the chances of weather that affect them take longer to work themselves out. That a nomad high should happen only every five hundred years or so by these means seems reasonable.

When there are too many lemmings on the tundra, the surplus must die, or fail to breed, so that the excess crop is removed. The same is true for nomads. Surplus nomads are spent as they follow their great captain in his armies to pitch their tents in border lands once held by civilized states…Population highs of nomads must now be translated into armies of aggression, which is easy. Nomadic people fight over pastures and water holes anyway; more nomads on the move means more fighting in bad years; more fighting means better attention to weapons and generals; and this means the chance of raising a real army.

The steppes are relieved of their surplus people and nomadism there may revert to its traditional ways...Fighting is no longer so necessary to the stay-at-homes and the martial needs of the people which made them submit to the triumphant discipline of their generals can be relaxed. This explains the ebb tide of nomad conquests...In this way does the ecological hypothesis provide a rational explanation for the periodic wars of conquest undertaken by nomadic peoples... (pp. 197-203)

The nomad armies were never beaten. In the end they merely faded away. Like the decline of more conventional empires, this has often been seen by moralists as the result of a loss of spiritual purpose in the descendants of the conquerors. They grow soft, take to loose living, wallow in their harems, and forget that the martial graces are supposed to be superior. But such moralizing is not necessary to explain the ebb of the Mongol aggressions. The need, which had caused the people to throw up that dreadful army, had been satisfied. The wars had first diverted the frustrations of a rather crowded people with adventure and plunder, and then had removed the cause of those frustrations entirely by effecting an armed emigration. (p.210)

If there is a major flaw in this portion of the book, it is his focus on Western world history to the exclusion of Asian civilizations, especially India and China. This most likely is because the book was published in 1980 when much less attention was paid to Chinese and Asian history, and much less scholarship was available.

Which is too bad because China's history provides confirmation of his ecological hypothesis. The weight of numbers has always been the central fact of Chinese history thanks to their highly efficient food-production techniques. China has also been shaped by warfare and conflict for over 3,000 years. They were unable to break out of this pattern and expand niche space through technology or colonization like the Europeans were able to do; indeed Chinese culture was famously insular and solipsistic. This led to caste systems and cultural stagnation, exactly as Colinvaux describes. In fact, Ancient Chinese historians were among the first to describe their history in terms of repeating cycles in books such as the Shujing, or "Classic of History."

China's rise since 1980—when the book was written—has seen further confirmation of the ecological hypothesis: rising numbers, rapid growth and industrialization expanding space in the broad niches, repressive government, abandonment of the countryside and urbanization in the face of population increase, extreme concentration of wealth, and now, potentially, imperial expansion, war, and colonization. At the same time, the United States' parallel decline—with falling living standards, a burgeoning surveillance state, a de facto caste system created by costly higher education, rising costs of living, warring tribal factions, burdensome debt, and an insular, out-of-touch elite—can also be seen as a further confirmation of his thesis.

Having reflected on the past course of human history throughout the book, in the final chapters Colinvaux ponders humanity's future. He points out that society has been relieved from many of these pressures for the last few centuries by the extraordinary expansion of industrialism ultimately powered by burning fossil fuels. But these circumstances will not last forever, he assures us. Eventually the planet will fill up and the same forces will once again be at play:

Western society has been built on the treasure hoard of fossil fuel lying loose at the surface of the earth. It is as if we have been living on the loot of some vast and undetected robbery. But the loot is far gone. The oil may be half used, or more. There is still coal, but the best, or at least the most easily reached, is gone. We have bred very large populations to use this cheap fuel so that our use is now at a rate which means that the remainder must be spent far more quickly than what we have used already. And now the rest of the world wants to use fuel as we have done. We must share the swag—what there is left of it.

This means that energy will soon be expensive whereas once it was cheap. It is not that we will run out of energy; it is rather that we will run out of cheap energy. Indeed, we already have, though present (1980) prices are still absurdly low by the standards of what will be the norms ten years from now. Oil, and then coal, will soon be so expensive that nuclear reactors will seem economical to run. We can then pursue research into whatever esoteric methods of energy production we like. There will always be energy, but at a very high price. Never again win energy be cheap, plentiful and easy to extract. This is a fact with profound implications for the politics of nations.

Cheap food too has gone forever. The good parts of the earth are all farmed, and the yield does not quite keep up with the demands of the increasing numbers of people, the crops of the green revolution will be extremely expensive to produce as energy prices rise, probably, in fact, too expensive for poorer countries to use them at all. To the extent that these new crops are abandoned, food production will actually fall, requiring that prices go up in response to the increasing imbalance of demand and supply. Demand too will grow as our numbers continue to grow. In the productive agriculture of the West, farmers will have to start economizing in the use of tractors and fertilizer, as their energy costs climb. They will find themselves using more labor, both human and animal. Their yields need not fall, but the price must go up.

We are, therefore, moving into a time when both energy and food will be dear. Many patterns of civilized life are about to change as a result. The spreads of cities will be different, the countryside will be repopulated, there will be quite different patterns of work and play. It may not be something to fear; it may be rather an opportunity, like all change, for the most adventurous to welcome. Perhaps we can dismantle city governments, break monopolies of power, live country lives when we want to, and work in small industries for brave entrepreneurs instead of serving some giant corporation. Change is always good for the brighter spirits, and the high cost of fuel and food make drastic change inevitable. But the new patterns must certainly offer new temptations and straits which might drive nations to battle, even nuclear battle. (pp. 336-337)

As I write this authoritarian politics have exploded in popularity worldwide, there is once again war in Europe, fertilizer costs have spiked driving up the cost for food, gasoline prices are at historic highs driving up inflation, there is a dire shortage of baby formula in the United States, and housing costs in industrialized nations have skyrocketed, especially in the most desirable and prosperous locations (a clear effect of overcrowding). Meanwhile temperatures in India and Pakistan have surpassed the limits of human endurance, the American West continues depleting its water supply, the Horn of Africa is being ravaged by its worst drought in four decades, Indonesia has banned the export of palm oil, and India the export of wheat. Even nuclear war is back on the table. I could go on and on. Perhaps we should stop listening to economists and their cornucopian techno-fanasties and start listening to what the actual scientists have to say. Before it's too late.