This review is a modified version of one posted on my old blog from 2016. Sorry for the erratic page numbers. Emphasis mine unless noted otherwise.

The Fates of Nations by ecologist Paul Colinvaux takes a look at human history through an ecological lens. Colinvaux presses into service basic ecological concepts but uses them in a novel way to describe the dynamics of human societies leading to some interesting conclusions. He then uses these concepts to explain some of the big trends we see throughout history like trade, conquest, urbanization, colonization, class conflict, and so on. His ideas are very similar to—and can be seen as a precursor of—the theories of history developed by Peter Turchin, himself also trained as an ecologist.

Colinvaux's outlook could be described as Malthusian. In his depiction of history, the weight of numbers is a basic, fundamental factor, just as it is with any other animal. No matter how big or how small, organisms have been shaped by natural selection and Darwinian forces continue to operate on every organism—including humans. What makes humans unique, however, is that our responses to those evolutionary forces are unique and very different from other animals. Humans live in large, complex societies, we have persistent, cumulative culture that is passed down generation to generation, and we can reshape our natural habitat to a much larger degree than other animals.

Colinvaux's approach gives some really interesting insights into large-scale social processes which I think is valuable. Some might complain that it takes human agency out of the equation—and indeed, Colinvaux explicitly rejects the "great man" theory of history. Environmental conditions and social instincts are what drive human societal processes, he says, not beliefs or ideas. Rather, our beliefs and ideas are often post facto rationalizations based on ecological and material pressures that we mistakenly assume are driving the car rather than merely being passengers. In other words, societal beliefs and ideas are responses to material conditions rather than shapers of them.

I should state at the outset that I don't agree with everything he says. A counter-argument is that humans have more control over their reproductive strategy than Colinvaux gives us credit for, and we aren't just another unthinking animal like rodents or sparrows or anteaters. It’s notable that this book was written in 1980 at a time when overpopulation was a major global concern, but we can already see birthrates falling all over the world today (much the consternation of economists). Nonetheless, I'm going to present his theories exactly as he wrote them to the best of my ability, so don't assign them to me if you disagree!

So let's dive in.

Colinvaux begins by introducing two central concepts that will come into play throughout the book: niche and breeding strategy.

As Colinvaux describes, a niche can be thought of as the way an animal makes its living. The niche of a panda is eating bamboo shoots. The niche of a koala is munching on eucalyptus leaves. The niche of a lion is hunting gazelles. The niche of a vulture is consuming carrion. The niche of a hyena is scavenging carcasses. The niche of a squirrel is to gather nuts. And so on.

The breeding strategy is dependent upon the niche. In Darwinian theory, every animal has more offspring than is required to replace their parents. As Colinvaux puts it, each animal has the number of children they think they can afford. Since there is no coordination across members of a species, each mating pair produces the optimal number of offspring that ensures that their genetic material is passed along into the next generation in a sort of arms race. Differential survival rates among those offspring is what drives evolution according to Darwinian theory.

Because animals always produce more offspring than their niche can support, this leads to competition for available resources within that niche. No matter how many offspring each pair has, the niche itself remains a fixed size. This sets up competition between the members of a species for niche space. Excess offspring are then winnowed down by competition. For most animals, the size of a niche is determined strictly by the amount of food and space available:

Producing more offspring has no effect on the size of the niche. When an animal lives in a fixed niche its population is fixed as well, no matter how vigorously the animal breeds." (p.53) "Each individual is programmed to thrust as many descendants as possible into the next generation, and it is competition for niche space that winnows the surplus. (p. 52)

Given these conditions, the optimal number of offspring for any breeding pair is dependent upon the niche that they occupy. Have too few children and your genes will not get propagated into the next generation. Have too many, on the other hand, and your children will not have enough resources to survive also ensuring failure. Therefore, each species independently arrives at a "Goldilocks strategy" to produce the optimal number of offspring to ensure their continued survival.

The higher up on the food chain you are, the fewer offspring you can afford, since you need a lot more resources to survive than animals lower down the food chain. Thus, large animals and apex predators are always the rarest animals in any ecosystem. The breeding strategy of these animals, therefore, is to rear fewer offspring and invest a lot of time and effort into each one. It’s a quality over quantity strategy (in ecological terms, k over r).

The further down the food chain you go, the more this reverses, until you come to animals that produce thousands of offspring where only a small number will survive. For animals lower down the food chain, then, the best strategy is to gamble with a larger number of offspring hoping that enough will survive the odds and pass their genes along to the next generation (even though most will not). Therefore the breeding strategy is set by the niche. These are two interlocked concepts. As Colinvaux puts it, each animal breeds in line with its niche.

Having a few large young, and looking after them, is the best way to press your descendants into the populations of the future...But even for those animals with the prudent banking habits of the large-young gambit, there must still be a pressure to raise the greatest possible number of babies, producing a tendency to make the modest family hold just one youngster more.

The tendency is blocked or balanced by the danger that lies in trying for too large a family. If a couple tries for one youngster too many there may not be enough food to go round and the whole brood may be in jeopardy. One youngster too few, and your neighbors' descendants will swamp yours. One youngster too many, and you tend to lose whole line.

The one that wins will be the one which starts with exactly the right family size: the largest number of babies that can be reared on the food available, and not one baby more. There will, therefore, be an optimum family size for any species using the large-young gambit, and habits which result in this optimum family will be preserved by natural selection.

The human breeding strategy, then, is based on sexual habits that lead to a surplus of babies, balanced by patterns of behavior that reduce or halt this continued accretion by culling. The methods of culling are either deliberate (infanticide) or properties of social behavior (taboos) that probably serve a number of other functions as well. But, whether by infanticide or learned taboo, these methods of stemming the flood of babies to what is convenient all result from the use of intelligence. It is the purely human quality of a developed intelligence that allows our curious sexual appetite to be a useful part of our breeding strategy.

Humans evolved in the ecological niche of "big, fierce predator," meaning that our numbers were small for most of our existence as a species. In any ecosystem, big, fierce predators that eat meat are always rare because they only capture a small portion of the earth's solar energy as it is passed down the food chain, beginning with the primary producers who use the sun's energy directly through photosynthesis. Only a fraction of the sun's energy is available to big, fierce predators: "Humans were rare as tigers are rare, because there is not much food to be won at the profession of big, fierce hunter." (p.53)

As Colinvaux describes it, humans are fundamentally creatures of the Ice Age. Far from being a harsh environment, the Ice Age is the environment for which we are most ideally suited. While northern regions were indeed colder, most humans were concentrated in the wide bands around the tropics, and the water locked up in glaciers meant that there was actually more land available in these regions, while grassy savanna ecosystems covered more of the planet's surface teeming with potential prey. As a result of this environment, humans have evolved to prefer wide open spaces and to value freedom, novelty, and choice.

When the last Ice Age ended, the climate warmed and much of the earth's big animals disappeared. The glaciers receded and coastal areas became submerged under water. The savannas shrank and became woodlands and forests replaced tundra. Humans found their optimal foraging niche shrinking, forcing them to embark upon a radical experiment.

Humans can exert a much greater degree of control over our natural environment than any other species due to our big brains, hypersociality, and tool use. By doing so, we escaped the hard limitations of our niche which constrained most other animals. We began to divert more and more of the earth's primary productivity to ourselves, depriving it from other living things. We produced surpluses and stored them. Ecologists refer to this as niche construction. Our breeding strategy, however, remained unchanged—each individual still had the number of offspring they think they can afford:

Increasing the food supply by changing the niche gave our perfected breeding strategy a chance to show of what it was inherently capable. Unless we changed the breeding strategy, which we have never done, there would, inevitably, be a great increase in the number of people living. Each individual, remember, is programmed to try to thrust as many descendants as possible into the next generation, and it is competition for niche space that winnows the surplus. But, if more niche spaces can be made almost at will, there will be no more competition. All offspring raised to maturity will find a niche in which they can live and raise offspring of their own.

The Darwinian breeding strategy of the animal that can create unlimited jobs for its offspring would lead to an unlimited number of survivors. Substitute the words "very large" for the word "unlimited" in the above sentence and we have one of the results of the great people-experiment of changing the niche without changing the breeding strategy: people have overrun the world.

When we lived in a constant niche like all the other animals, there were essentially no population consequences of this perfected breeding strategy of ours. As the niche never changed, so the numbers of the people never changed. What has changed since those ancient times is not the breeding strategy, but the niche.

Original niche learning had little effect on our numbers, because every culture exploited similar varieties of foods. We were always hunters or gatherers. Ancient people learned their professions of life, just as the followers of modern professions learn theirs. It was this fact that made us ready for the dramatic changes of niche that were to come later.

We have learned to live not only as hunters or gatherers, but as farmers and industrialists as well. These are quite different ways of life from those of our ancestors, and they can provide for populations of quite different sizes. This is why our populations have grown since those early days: because the niche has changed. All of us still breed to press more of our descendants into the next generation than there is room for. In the old days this made no difference, because the job opportunities of niche never changed. When we started to change our niche, the opportunities for life went up, and our numbers rose accordingly. (p. 51)

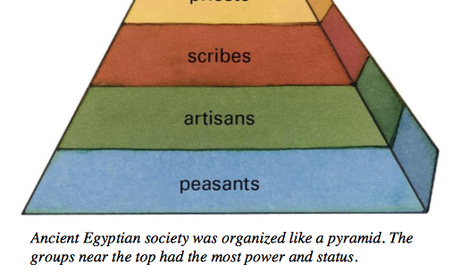

When we switched to growing our own food, the niche concept changed as well. This is one of Colinvaux’s key insights. Now, a niche no longer meant simply they way an animal makes its living in the wild, but how humans make their living in a society. One's niche was no longer about how much sustenance you could procure directly from the immediate environment the way hunters and gatherers do. Instead, it was one's role in the large, complex societies we came to inhabit. New niches emerged as civilization developed such as farmer, herder, artisan, merchant, priest, king, scribe, soldier, and slave.

Following ecological principles, Colinvaux dives social niches into broad niches and narrow niches. For humans, a niche is not about survival but about the amount of resources one able to command. Broad niches are what we colloquially describe as wealth, and narrow niches are what we normally describe as poverty. Both of these definitions fundamentally revolve around resource use. Wealth and poverty are simply the terms we use when describing how many resources one is able to command. Poor people are highly constrained by their limited access to resources; rich people less so.

The organizers in a city-state, be they governors, bureaucrats, businessmen or priests, led active, wide ranging lives that needed many resources; an ecologist would say that they had a broad niche. The mass of the people needed much less, little more, in fact, than would be wanted by that ideal agricultural peasantry; they had a narrow niche.

The broad niches of the governors meant wealth, but then the narrow niches of the mass could be given a new name, "poverty." "Wealth" and "poverty" are but names we give to two extreme kinds of ecological niche. The niche of wealth demands more resources per individual than does the niche of poverty. Wealth even takes more food, for a wealthy person actually eats more calories than does a poor person. Even more importantly, the wealthy person tends to eat higher on a food chain, requiring more meat.

This means that any patch of real estate probably can feed between ten and a hundred times as many of the very poor as of the very rich. How many rich people there can be, therefore, depends on how many people are trying to get their living from the land; it depends on population density...Wealth and poverty are both inventions of agriculture-based humanity, but poverty is more of an invention than wealth. We make people poor by denying them the types of food, activities and space that were consumed in the primeval human niche, whereas the wealthy retain many of these old assets.

With the rise of large-scale societies, many people became crowded in the less desirable narrow niches. Meanwhile a much smaller number of individuals were able to occupy the highly desirable broad niches at the upper echelons. The majority of people who occupied the lower niches were compelled to get by with fewer choices and less living space than their Ice Age ancestors had enjoyed. Their lifestyles were constrained by resource scarcity, just as the supply of food constrains the niche of animals in the wild. People occupying the lower niches were forced to cope with overcrowding, disease, malnutrition, celibacy, and backbreaking stoop labor. This led to the existence of wealth and poverty, where the wealthy can command ten, fifty, a hundred, or even a thousand times more resources than the average person—something not possible for the hunter-gatherers of the Ice Age.

Eventually, people became crowded together in city-states and became sedentary food producers. Intensification allowed the population to grow to previously unachievable levels when we were mobile hunters following the herds. This crowding eventually led to the need for a managerial class to ration and distribute those resources, and the people who undertook these roles occupied the most desirable niches in any society. According to Colinvaux, because big-game hunting requires a high degree of specialization and top-down coordination, we were already primed by our Ice Age lifestyles for this form of social organization. Once we settled down we permanently escaped the limitations of our previous ecological niche, and management, hierarchy, specialization and control became permanent features of our societies:

The organization that we call a "city-state" is the logical, indeed the inevitable, outcome of the invention of agriculture by an animal of social habits. Agriculture requires settlement. An unchanged breeding strategy makes that settlement dense. Government in a dense community requires specialization. And a dense settlement containing both rulers and ruled must inevitably divide up the country into land to live on and land to farm. The city-state has emerged, along with a rationale that requires people within it to have different specialties—that is, different niches...

Our primeval niche let us take kindly to government because the old social life involved divisions of labor. Hunting in groups needs collaboration and mutual support. Even herding, which ties people to beasts, requires some directed collaboration, and agriculture ties people to ground and food plant, so that government for any society more dense than a one-family plot is essential. The institution of government did away with the nightmare of people being reduced to perfectly equal peasanthood. But escape may be only for the fortunate few—the governors.

The need for government in dense communities did more than just save a few individuals from the worst consequences of our change of niche. It also allowed further increases in the carrying capacity. Government could ration, distribute and hoard. Surplus and deficit could be balanced from place to place, and from season to season, ensuring an even flow of the necessities for life, making the luxury of large families the more safely enjoyed. By contrast, life was much worse for the vast majority of peasants who lived under the whip of an overseer. (pp. 68-69)

The invention of institutions to cope with growing numbers is an ongoing process, continually unfolding, and the mismatch between our Ice Age habits and our modern circumstances is the underlying cause of many of social maladies we see today, from drug addiction, to teen pregnancy, to child abuse, to depression, to obesity.

The people occupying the broad niches in any given society have access to many, many times more resources those lower down the hierarchy, so those niches must necessarily be rare, just as animals occupying the broad niches are rare in nature. The niches toward the bottom of the social pyramid, by contrast, require much fewer resources to survive, and so many more people can occupy them. This is why there must always be more poor people than rich people in any society according to Colinvaux. In other words, the “social pyramid” mirrors the trophic pyramid to some degree, because of the inherent resource limitations present in any society.

We no longer live in the ancient human niche, but we still could, or rather, some small number of us could since there would not be room for many. It must, therefore, follow that we still possess the traits that equipped us for that ancient niche, even though we have turned our skills into living in quite different ways. We have invented and learned most of our new ways, so they must be wholly new. But some of the ancient adaptations that we did not have to learn are still with us. (p. 47)

The immense flux of resources required for each niche-space of wealth can best be realized by reflecting on just one propensity of the wealthy, the propensity to choose. The wealthy seek variety, both in daily activity and in real opportunity. But any freedom of choice must mean that, for everything done, there be something left undone. Freedom and wealth, which are to some extent linked, require very many resources per niche-space. The wealthy, and the truly free, therefore, must be rare. (p.71)

However, the people occupying the narrow niches will typically aspire to living in the broad niches, because those niches most closely replicate the lifestyle we had evolved to thrive in during the Ice Age—with an abundance of living space, freedom, novelty, and choice. Therefore, competition for places in the broader niches is intense, the same way as competition for niche space in an ecosystem is intense. However, just as in nature, there are always far more aspirants to the broad niches than there are places available for them. There are simply not enough resources in any society for everyone to live in a broad niche. The result of this is class conflict:

We must think that our most perfect evolutionary triumph would be a society of agricultural peasants, sedentary, marvelously numerous, living in a landscape set the very minimum of animal food, freed from the very minimum of animal food, freed from the threats of predatory or competing animals, and having a family size again brought down to meet the needs of replacement and set by the fact that there should be no food to rear more than two or three children per couple. Peasants such as these would be the ecological apotheosis of humanity...

But people have not been able to change the human niche so completely as required by this triumphant evolutionary nightmare. They have not wanted to be the perfect food-raising food-consuming peasant. Many individuals resist peasanthood very strongly indeed, trying to preserve more ancient ways of life and even wanting to do things that the ice-age peoples could not do; they want to go adventuring like a hunter, to paint, to craft, to make machines...

It's a bit of a conceptual leap to see occupational specialties and social roles—and the resulting wealth and poverty—as the equivalent of ecological niches. But this allows Colinvaux to go to some interesting places.

Foe example, if we think of occupational specialties as a niche, then just like the size of a niche in ecology is fixed, so too is the size of any occupation in human societies. That doesn't mean it can't grow or shrink over time, of course, only that the size of the niche is not determined by the number of people who want to occupy it, just as the size of an ecological niche is not determined by the number of offspring an animal produces.

An example he uses is the "niche" of aeronautical engineers. In any society, there are only so many spots for aeronautical engineers. That niche is finite; it cannot expand simply by producing more aeronautical engineers, rather, it can only expand if there is a greater societal need for aeronautical engineers due to things like a boom in the aerospace industry or the discovery of new technologies. The same goes for doctors, nurses, lawyers, accountants, plumbers, carpenters, computer programmers, architects, political representatives, consultants, or every other profession you can think of:

We know that the number of people who can earn their living as aeronautical engineers is set by the job market for these highly specialized skills. The number of people actually filling the niche of aeronautical engineering cannot be altered by training more engineers in college but only by making the aircraft industry boom. An ecologist would say that niche-space determines the population of the species "aeronautical engineer," just as niche-space determines the number of squirrels. Similar arguments apply to all human professions, just as they apply to all kinds of animal niche.

As Colinvaux argues, if you expand the number of candidates for a specific niche without a corresponding increase of the size of that niche, all you will do is increase competition which will inevitably produce more social conflict not less. For example, the number of spots in PhD programs or medical internships is limited by a number of institutional factors. More aspirants to those roles, by itself, does not increase the number of those roles—it only leads to more competition for them. In other words, the "niche" of doctors or academics is fixed and can only expand via societal factors (such as expanding the number of medical schools or universities, for example):

Western societies have recently tried a large-scale experiment in flooding niche-space when they expanded the university population, particularly the graduate schools...Universities have produced very large numbers of these presumptive professors, rather as if the squirrels had a very good year for raising young. But the number of professorships sets the opportunities for professing...Now surplus bearers of doctorates cannot accept the scholar's tenure, however cum laude their degrees...

People have the quality, not shared by other animals, of changing their niches. Surplus squirrels always die, but surplus scholars, lawyers and aeronautical engineers take up other trades. Yet it must be remembered that all human professions have this in common with animal niches, that the number of individuals following each profession, or niche, is absolutely set by the conditions of their ways of life. Niche sets number. (pp. 28-29)

A corollary of this is that more education does not magically call forth the need for more jobs. Thus higher education, far from being a magic silver-bullet solution for poverty, often leads to more problems than it solves. Colinvaux tells us that in places like Africa, there are already more educated people than there are niches available for them. Many of those educated poor leave and go elsewhere where they increase competition for niche space in wealthier societies leading to cultural clashes and increasing competition for a limited pool of jobs. This is especially relevant given economists' argument for "more education" as the solution for the poverty and overpopulation in the developing world. It also is why increasing education and mass immigration has not resulted in rising living standards for the majority of people in highly developed countries, since it increases the competition for niche space:

When a country starts on mass education even before there is a rapid expansion of the niche-space through technology, as many in the Third World are doing now, the result must be a social crisis. The crisis is like the excess production of aeronautical engineers, which I described earlier, but on a national scale and for all the appetites of middle- or upper-class life.

In a version of the old saying about more chiefs than Indians, it is a deliberate production of more chiefs than there are chief jobs available. The only escape for the surplus of the newly educated in one of these countries is emigration, if some more developed country will take you; the only escape for the government is repression of the new intelligentsia. The developing world is rich in examples of both these measures. (p. 79)

This is similar to Peter Turchin's concept of elite overproduction. Turchin argues that the number of elite aspirants tends to increase over time much faster than spots available for them—the “broad” niches in Colinveax's terminology. Therefore the competition for elite spots becomes more and more intense and acrimonious over time.

For example, in recent times the supply of lawyers has increased much faster than the number of lawyer positions available for them. This has led to a bifurcation in incomes. Rather than most people earning around the median salary for a lawyer, incomes follow a bimodal, or "camel backed" distribution pattern where they are either far above, or far below the median income—with little in between.

In Turchin's formulation, the frustrated aspirants in this scenario don't just go away, rather, they become counter-elites. As counter elites wage war against the system that excluded them, they recruit allies to their cause and societies start coming apart as rival groups coalesce into mutually antagonistic factions that see the other side as the enemy. Social cooperation breaks down. If this process continues unabated, it can eventually lead to the dissolution of the society, revolution, or even civil war. This is one of the grand cycles of history according to Turchin.

Even though we transitioned to living in sedentary, agricultural societies, our breeding strategy remained unchanged—each couple continues to raise the number of children they think they can afford. This leads to one of Colinvaux's other key insights: that, counterintuitively, the rich will always have fewer children than the poor. This is because, just as animals higher up the food chain have fewer offspring because each individual offspring requires more resources, people higher up the "social" food chain also require more resources, and will thus opt to have fewer children.

The children of rich couples require a lot more parental investment in terms of elite education, foreign travel, luxurious accommodations, individual tutoring, designer clothing, enrichment opportunities, recreational activities, and so forth. By contrast, for those living in poverty, children require only minimal resources. Therefore, just like animals lower down the food chain, the poor will produce a lot more offspring. There are almost always enough resources for yet another humble pauper, but not for another prince, and therefore, "each human way of life will have its own characteristic size of family." (p.41)

Because it takes scant resources to raise a child in poverty, the hopelessly poor will opt for large families. They are doing their Darwinian thing, estimating the number of children that can be raised to compete for niche-spaces in their world of chronic poverty and then arranging to have families of this calculated size.

The wealthy, on the other hand, must plan for each child to be able to compete for niche-space in a world of wealth...When the Darwinian cost-accounting is done in a wealthy family, the stark fact is that the certain and successful rearing of a child, fully equipped to become itself a parent in its parents' world, requires a very heavy investment. Wealthy parents, like poor parents, seek to raise the largest number of children that they can afford, for this is their animal breeding strategy which has never changed. But wealthy people cannot afford very many children, despite their wealth. (p.42)

(This can be vividly seen today, for example, in the endless steam of articles about "power couples" in places like Manhattan, Washington DC and Silicon Valley who earn high six- and even seven-figure salaries while vociferously complaining that they don’t feel wealthy and can't make ends meet.)

As the number of poor people increases, so too does the pressure on the upper levels of the social pyramid. Another of Colinvaux's insights is that the effects of scarcity and crowding are first felt more keenly in the ranks of the upper classes rather than in the lower classes. This is because the lower classes are accustomed to a lower standard of living, but the wealthy are not. The wealthy and their offspring demand more resources per capita to support their luxurious lifestyles than the masses:

A broad niche requires numerous resources; an expansive way of life can be provided for only relatively few. But more young people equipped to live in an upper-class way will keep coming in succeeding generations as our breeding strategy manufactures more people. Niche-theory predicts, therefore, that rising numbers will always cause trouble for the wealthy before they cause trouble for the poor.

This is counterintuitive. We naturally tend to assume the effects of overcrowding and scarcity will be felt more keenly by the lower classes, and that the resulting absolute deprivation, misery and poverty will eventually drive them to revolt.

Not so, says Colinvaux. Rather than revolutions coming from below, the swelling ranks of the poor will put instead pressure on the lifestyles of the upper echelons who will resort to various measures in order to try and preserve their living standards in the face of growing population pressure and resource depletion: "Politicians nowadays talk of "the population problem" as if it were mainly a worry for poor nations and the underprivileged, but this is wrong. The wealthy are the ones to be squeezed because the wealthy use the resources that the new crowds will want." (p76).

This once again echoes Peter Turchin's theory of Secular Cycles in which an extractive elite (those who occupy the broad niches) becomes ever more rapacious over time in order to try and preserve their living standards in the face of increasing resource scarcity due to population growth. This also leads to social breakdown.

In any society the breeding strategy is based primarily upon hope, specifically the hope that one's children will enjoy a higher living standard than oneself. The result is that growing, prosperous societies will inevitably lead to growing populations, which will in turn eventually undermine rising living standards leading to a loss of hope and an increase in despair. It is at this point that Colinvaux's argument becomes more explicitly Malthusian.

In every human society, he says, population growth will eventually outstrip available resources in the long term. Technological change and intensification can call forth more resources for a time, of course, but this strategy was necessarily limited in the agrarian world. Colinvaux’s argument is that population growth—and subsequent overcrowding—is the fundamental cause of poverty and social unrest. Note that his ecological argument is the exact inverse of modern economic “science,” which touts increasing population as the source of wealth and prosperity, and even a slight downturn as a cause for alarm. It is also similar to Turchin's Secular Cycles, where increasing population growth during the expansion phase of a society gives way to a stagnation phase once the available land has been occupied and resources have been used up.

Every couple, rich and poor alike, continued to rear as many children as it could afford. Numbers always rose. The extra resources wrung from the land by cleverness and industry always went to supporting more people at the old levels. As fast as a few individuals could be raised out of poverty, as fast as the actual numbers of people living richer lives increased, so also more babies were born into the world to swell the actual numbers of the poor.

Population growth is a geometric, or exponential, process. The cleverest of people, and the most enlightened of governments, have never increased the flow of resources exponentially at an even faster rate than the growth in demand represented by the extra mouths, except for short periods of rapid technical advance.

Industrial societies of the West are experiencing one of those short periods of rapid advance at the moment, and there have been others in the past. But always a plateau has been reached. It must be so. The rate of increasing production falls but the rate of population growth does not fall. Then poverty must get worse and more visible, for not only do the numbers of people who must be poor increase, but each poor family finds itself poorer and poorer...Ecology's first social law may be written, ''All poverty is caused by the continued growth of population." (italics in original)

Colinvaux is pessimistic about the idea that the demographic transition—the idea that as as societies get richer people tend to have fewer children—will lead to less resource consumption in the long term. Each couple still has the number of children it thinks it can afford no matter what, and as a society grows richer that number will also tend to increase. Wealthier couples may indeed have less children overall, but population growth will still continue unabated as long as living standards continue to rise, he says. And since rich children require more resources per capita than poor children, relying on increasing living standards to take pressure off the environment is a strategy doomed to failure:

Smaller families for the rich than for the poor are explained and predicted by the ecological analysis of the human breeding strategy, as we have seen. But this does not mean that numbers in a rich society will not rise, only that they will rise more slowly. Breeding strategy still ensures that each couple will raise the largest number of children it can afford and, under most conditions of wealth, this is likely to be more than enough to replace the parents. Making the poor wealthy will slow the rate at which children are raised, giving us more time to anticipate or plan the historical happenings that their crowding will bring, but it can never stop the children coming in excess supply. (pp.42- 43)

It can happen, and often does, that populations grow more quickly in poor countries. But this does mean that populations do not grow in wealthier states as well. In fact, we know that they do...What matters is the eventual population density. It is the number of people per unit of resource that determines the size of a niche and, hence, what we call a standard of life. Coping with more people in each succeeding generation is the ultimate drive for technical innovation...But poverty will always be present, because any large increase in resources produced by new technology will be taken up within a few generations by the provision of more poor people. (pp. 73-74)

Colinvaux argues that only chronic, grinding poverty and permanently lower living standards has been shown to slow or halt population growth in the long term:

But it is still possible for the human breeding strategy to cause population losses, as well as population gains. This will happen when a community is reduced to such despair that the average opinion of the ideal size of family puts it close to zero. Or, if hope yet allows some couples to start families, then the conditions of the people are so desperate that they cannot succeed. A single generation of desperation can remove a whole community for good. It is to this possibility of near total failure of the breeding effort, not to massacres of adults, that we must look for the decline of populations in history...(p. 44)

It is when the effects of overcrowding and resource depletion start to seriously bite into the living standards of the upper echelons that they will turn to a variety of strategies in order to cope with it. That is, revolutions come from above, not below.

One option was simply repression. This involved basically shutting down all routes of social mobility—and hence avenues to prosperity—in order to preserve their place at the top of the hierarchy. Often this involves establishing some sort of caste system, whether formal or informal. Under caste systems people are simply assigned to the less desirable niches with no possibility of escape. A caste system precludes social mobility, but ensures social stability. Colinvaux notes that many of the most stable societies in human history were ones that implemented strict caste systems, especially in Asia. Since aspiration is fundamental to human nature, however, these societies typically had to implement highly repressive systems of government and politics in order to preserve the social hierarchy and keep people confined to their assigned places.

The other option involved finding various ways to expand the available niche space, especially among the broader niches. There were several ways to accomplish this. One was colonization—the expulsion of the surplus population to found colonies on virgin soil. Another was violent conquest—the seizing of land and resources from neighbors through brute force. A related strategy was the establishment of a far-flung empire—either by land or by sea—funneling distant resources from the hinterlands to the imperial core. Finally, trade—especially adventurous, buccaneering trade carried out in remote lands—was a way of expanding resources and niche space in domestic populations, both for the traders as well as the wider population.

For the early stages of the growth of a civilization, therefore, niche theory predicts life in settlements, continually rising numbers, a ruling class living in broad niches that include many dimensions of the primeval human niche, technical innovation from those who have broad niches already, the persistence of poverty, and an actual increase in the numbers of the poor.

Ruling classes that feel themselves threatened by the social pressures of a rising population have only two courses of action open to them. They can find more resources to provide good niches for more people or they can restrain the pressure on niche-space by a system of oppression. The most interesting ways of increasing the flow of resources include trade, colonies and war. These are always tried. The alternative, constraining the appetites of rising numbers by some system of force, is also always tried. It involves regimentation, bureaucracy, class, rationing and caste.

Therefore, it is population growth since the end of the last Ice Age, combined with humans escaping the ecological niche for which we had evolved, which serves as the main driver for historical events according to Colinvaux—from wars of conquest, to the colonization of distant lands, to the intensification of agriculture and the abandonment of the countryside, to the establishment of buccaneering trade, to the rise of bureaucracy and repressive surveillance states. All of these are inevitable and predictable. In the rest of the book, Colinvaux explains how the subsequent ebbs and flows of history can be explained by the ecological principles he describes above:

Behind all the great climactic struggles of history we will find symptoms of an expanding population. Whenever people have been ingenious so that the quality of their lives has improved they have let their numbers rise. The demand for more resources for the better life has always been more than the prevailing political systems could provide. And the grand themes of history have been the result: repressions, revolutions, liberations and always, in the end, aggressive war.

Perhaps little wars and petty repressions can often be explained as being caused by no more than human wickedness and animal passions, as various social and biological writers have argued. But all the truly great wars of history, those that ended with shifts of peoples and the remaking of maps, were caused by increases in the numbers of people and associated increases in demand.

We can examine the wars, the growths, and the falls of civilizations from ecological principles which describe how resources must be divided between people and which show consequences of changing the numbers of those people. From this study a predictive theory for the fates of civilizations, including our own, will emerge... (pp. 23-24)

Next time we'll take a look at how those dynamics unfolded throughout history.

I dunno about birth rates falling. the UN just said we passed 8 billion people. So the birth rates aint falling. When I was born in 1965, we were 4 billion. AT the turn of the 20th century we were only 1 billion. No wonder WEF and the Davos and the Illuminati's main concern is how to cull the human herd. And in fact, I DO agree with them. We ARE far too many, far far too many.

I'm curious. One of the last we spoke, I asked if you had yet read Henry George' Progress & Poverty. George's outline of what stimulates the creation of poverty relates directly to Colinvaux's. For example, where C. notes that "Wealth and poverty are both inventions of agriculture-based humanity, but poverty is more of an invention than wealth," G. gives this a mechanism: rent. Those that own property (or any other necessary resource) can simply increase the cost to those that need it in order to prevent aspirants from attaining the wealth the property holders dominate. Of education (which G. notes many "…attribute to it something like a magical influence"), the two agree as well. A diploma or skill "…can operate upon wages only by increasing the effective power of labor." With no market for that labor—no niche—no improvement of condition. Once again, I think P&P is a book you cold sink your analytical teeth right into.