The Journey of Humanity

The demographic transition looms large in Oded Galor's grand economic thesis

In my previous post, I mentioned the book The Journey of Humanity by economist Oded Galor. This is another "big history" economics book profiled recently on the On Humans podcast. I was finally able to give it a read.

Galor's thesis is quite simple. He argues that the Malthusian dynamic we discussed in my review of Brad DeLong's Slouching Towards Utopia was indeed in effect for all of human history. That is, prior innovations and inventions always resulted in population growth, and the additional mouths to feed led to declining living standards after a relatively short period of time in a sort of vicious cycle. That is, we had larger, but not richer populations during the agrarian era, and people everywhere experienced long-term stagnation rather than growth, with living standards pretty much the same everywhere.

But he argues that, even though we were caught in this Malthusian trap, the fundamental tools to break free were bubbling beneath the surface. These tools were the result of our evolutionary heritage: a.) the unique human brain, which he says was the result of sociocultural evolution; b.) our social nature, allowing for large-scale cooperation and dissemination of knowledge; and c.) our tendency to innovate using technology.

The evolution of the human brain was the main impetus for the unique advancement of humanity, not least because it helped bring about technological progress—ever more sophisticated ways to turn the natural materials and resources around us to our advantage. These advancements, in turn, helped shape future evolutionary processes, enabling human beings to adapt more successfully to their shifting environments and to further utilise new technologies—an iterative and intensifying mechanism that has led to ever greater technological strides being made.

Positive feedback loops...have emerged throughout our history: environmental changes and technological innovation enabled population growth and triggered the adaptation of humans to their changing habitat and their new tools; in turn, these adaptations enhanced our ability to manipulate the environment and to create new technologies. As will become apparent, this cycle is central to understanding the journey of humanity and resolving the Mystery of Growth (pp. 16-18, emphasis in the original)

Thus, even though living standards stagnated during the long Malthusian epoch due to population growth, larger populations did provide one important benefit: they increased the rate of innovation as more and more people interacted and more and more brains were put to work solving problems. This, he says, laid the groundwork for the ultimate escape from the Malthusian Trap.

As will become apparent, this reinforcing cycle—technological development sustaining larger populations, while larger populations reinforce technological development—which has operated throughout most of our existence, gradually but continuously intensified until ultimately the rate of innovations reached a critical threshold. This was one of the sparks for the phase transition that hoisted humanity out of the epoch of stagnation (pp. 49-50)

Finally, during the Industrial Revolution, our ability to innovate reached the critical threshold where we were able to produce sustained higher living standards. But the key difference between this and earlier eras was that every previous period of prolonged growth resulted in more children per capita. During the Industrial Revolution, by contrast, he notes that people started having fewer children per capita. This is the dawn of what Galor calls “modern” economic growth.

Why did this happen? Galor argues that the greater need for “human capital” (using the econospeak term for more education) due to industrialization caused birthrates to fall. This demand for greater human capital led to couples having fewer children and investing more resources in them—including educational resources—rather than higher living standards translating into more offspring like during the agrarian era. He refers to this as a quality versus quantity tradeoff.

Lower infant mortality meant that it made greater sense to invest more in one's offspring because you knew that they would survive into adulthood, he says. In addition, as women's wages increased, the wage differential between men and women decreased, meaning that the opportunity cost of raising more children rather than being in the labor market incentivized having fewer of them. Finally, the more education one had, the higher one could rise in status, so parents invested in more educational resources for their offspring to encourage social mobility. All of this translated into having fewer children per capita.

Instead of a vicious cycle, this led to a virtuous cycle—more educated populations, in turn, became more innovative. As societies became more innovative, people had to spend a lot more time in education or training which suppressed birth rates even further. This led to the abandonment of child labor that we talked about last time. It also led to sustained higher living standards, ending the Malthusian epoch.

Wither Population Growth?

At first, this thesis seemed strange to me on it's face. Anybody who has looked into this subject knows that the Industrial Revolution led to an absolute explosion in population growth. One static I read recently makes the strikingly clear: between 1870 and the beginning of the World War One, the population of Europe had increased by 100,000,000, more than the entire global population before 1650!1 That is, industrialism supercharged population growth, not restricted it.

It took almost 12,000 years for the world’s population to increase from 4 million to 600 million people, but in only 320 years the total population has skyrocketed from 600 million to 8 billion. Since 1975, the global population has increased by a billion approximately every 12 years. To put this in context, the world’s population in 1950 was around 2.6 billion, grew to 5 billion by 1987, 6 billion by 1999, 7 billion by 2011, and reached 8 billion in 2022.

I think the explanation is the counterintuitive fact that, as populations undergo the demographic transition, the population growth rate doesn’t decline—it actually accelerates. This fact is well-known to demographers. Demographers explain this phenomenon by breaking the demographic transition into four stages.

In the first stage, the death rate declines but the birth rate remains high. People are still having lots of children to ensure enough of them will survive into adulthood. This keeps population growth high, even as the death rate falls, meaning that many more children survive into adulthood. The population pyramid looks like an actual pyramid, with lots of young people and very few old people.

Because there are a lot more surviving children, a lot more women survive to reproductive age. The growth rate accelerates as people pair off and start reproducing, leading to a population explosion—a phenomenon known as demographic momentum. This is the second stage, as Wikipedia describes:

A consequence of the decline in mortality in Stage Two is an increasingly rapid growth in population growth as the gap between deaths and births grows wider and wider. Note that this growth is not due to an increase in fertility (or birth rates) but to a decline in deaths.

This change in population occurred in north-western Europe during the nineteenth century due to the Industrial Revolution. During the second half of the twentieth century less-developed countries entered Stage Two, creating the worldwide rapid growth of number of living people that has demographers concerned today.

In the third stage, parents grow confident that their children will survive into adulthood and old age due to lower infant mortality and longer lifespans. The birth rate falls, causing the population growth the level off. People invest more resources in their offspring as Galor describes. The population pyramid becomes more elliptical, with more people in the middle age ranges relative to children.

In stage four, birth rates and death rates are both low. The number of women of reproductive age stabilizes. People only have the replacement number of offspring. The population stabilizes and the amount of older people relative to young people reaches near parity. Some have even speculated about a fifth phase where the pyramid inverts, with a declining population and top-heavy population pyramid with more elderly people than young people.

Confounding the situation is that fact that different parts of the human population entered into the demographic transition at different times, and some never have. This means that the human population as a whole keeps growing, and in many places is still increasing thanks to demographic momentum, even though overall human birth rates peaked years ago. This graphic illustrates the concept:

The dynamic is strangely absent from Galor's text, which makes it easy to get confused. Galor implies that the low living standards of the preindustrial era were caused by population growth. Then, he implies that the Industrial Revolution represented breaking out of the Malthusian Trap due to couples having fewer children per capita and investing more in them. But Malthus's solution to this problem was a stable or shrinking population, not a rapidly growing one, which, according to him would negate all of the gains from a growing economy. For example, Galor writes:

The Demographic Transition shattered one of the cornerstones of the Malthusian mechanism. Suddenly, higher incomes were no longer channeled towards sustaining an expanded population; ‘bread surpluses’ no longer had to be shared among a larger number of children. Instead, for the first time in human history, technological progress led to an elevation in living standards in the long run, sounding the death knell for the epoch of stagnation. It was this decline in fertility that pried open the jaws of the Malthusian Trap and heralded the birth of the modern era of sustained growth. (p. 85, my emphasis)

But population was rapidly increasing during this period, in fact, faster than ever before, despite the falling birth rates. Given this fact, why wouldn't the Malthusian mechanism still be in effect, at least until stage three? Why didn't demographic momentum eat up all gains from economic growth like Malthus predicted? And if innovation was the fundamental factor, why does Galor make such a big deal of the demographic transition? What does that have to do with it? It’s not clear.

Galor argues that what caused this decline in birth rates was the need for more education. But is that really the case? In a recent podcast2, Cory Bradshaw—an ecologist who studies population dynamics—pointed out that one factor stands above all others in terms of population growth. It's not education, either for children or adults. Nor is it female empowerment, the decline of patriarchy, economic development, or even religious beliefs.

According to Bradshaw, the largest single determinant of the growth rate is the infant mortality rate. Based on his research, there is a threshold effect: once the infant mortality rate declines to below around 0.03 (28.2/1000 live births = 0.0282), the birth rate drops significantly. Above that level, on the other hand, the birth rate skyrockets. Here is the paper: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4795464 The population quote above is from the same source.

So, if Bradshaw is correct, it wasn't the rise in return to human capital which caused the demographic transition as Galor claims (pp. 88-91). Yes, children did receive more education, but it was not the cause of declining birth rates. Rather, mass education may have become possible for the first time precisely because the birth rate declined so dramatically. Once again, we see that correlation is not causation. It was lower infant mortality that enabled parental investment, not parental investment that led to lower birth rates.

Aside from that, readers may have already guessed my primary objection to this thesis. When I discovered that Galor is at Brown University, I remembered that he was interviewed by Mark Blyth, also of Brown University, a couple of years ago. The interview is available on YouTube. One of the comments to that video by @stevefitt9538 echoes my own reservations about his thesis, so I've excerpted it below with a little bit of cleanup:

Prof. Oded Galor's argument IMO makes a common mistake of economists in mostly failing to look at reality outside of the elements of economics. It misses 3 important elements of why the inflection point happened about 1750 to 1776.

1.) The inflection point is exactly when England started burning coal to power factories making things, that added to the standard of living. Before this time almost all the things were being made by muscle power. So, more people making things didn't have much effect on the average number of things/person being made. More was made, but more people used them. There was growth as tech happened, but it was very slow.

However, when England started burning coal to make things, it was able to make many more things/person. In a sense, this was because people can't eat coal. So, all those additional things didn't let the population grow. It just let them live better.

2.) The amount of energy in the coal was far more then the muscle energy needed to mine it and move it to the factory. This resulted in an exponential growth in energy being used in England. This spurt would have ended, but by then the idea had spread to other coal mining regions in France, Germany, etc. and it kept spreading around the world. Soon, drilling for oil was added to the mix, which opened up more areas to keep the exponential growth of energy being used going strong.

3.) The reason that investing in fewer better educated children by England didn't result in an invasion by a neighboring nation with more less educated people was that England is an island and it could arm a tiny part of the population with cannons on ships to keep invaders out. All that coal could be used to cast thousands of iron cannons to put 74 to 100 guns on each ship manned by just 800 to 1000 men each. The ratio of fire power/man was just huge. So, is it likely that this process would have fizzed out if England had not been an island? Note how this question has nothing at all in anyway to do with any elements of economic thinking.

As for the origin of inequality, it is possible that [Paul] Romer was right that in the long run we would all live alike. It is just that the long run is longer than we have lived so far. Maybe in 200 more years he would have been proven right,

Now, we are coming to the end of this process. We are running out of oil and we can't keep burning fossil fuels anyway because of climate change. So, we don't have 200 more years to see if Romer was right. Also, we are coming to the end of the time of economic growth. IMO, we will have to learn to live with a much slower growth in living standards.

We need to realize in our gut (to grok) that Malthus was right all along (about the long run). He never claimed that there had never been times when people lived much better than their parents because for a short time the normal constraint had been lifted. I suggest that you look at US history from 1775 to 1890. In this just 115 years the frontier moved from down the middle of the states (that the western half of them was west of the then frontier) of NY, PA, VA, NC, SC, & GA to the Pacific Ocean. The people kept living better because they moved west to new land (empty after the Army moved the natives out of the way). Also, partly because of things being made in factories powered by coal. After 1890 the improvements were all because of burning coal. Malthus didn't factor in coal burning. However, in 1973, I saw that Malthus was right about the long run, and that I would live to see confirmation that I was right. And I have. Economists have yet to grok that Malthus was right.

Another comment to the video reads:

Interesting thesis. It doesn’t account for the inflection point in EROI ( energy return on investment) when certain societies switched from biomass to coal. That improved EROI from about 5:1 to 100:1, giving those societies a sudden energy surplus with a corresponding reduction in labor and land required to obtain that energy. It also released economies from the annual cycle of biomass production by tapping into a sixty million year accumulation of carbon.

Advances in public health in the latter half of the 19th century, at least in Europe and the US, reduced child mortality from around 45% to the low teens in the 1890s. That lowered the incentive to produce “spares,” even as the demand for agricultural labor dropped due to mechanization.

The book also fails to provide a good explanation as to why this shift to “modern” economic growth took place when and where it did, and not before. His explanation seems to be that once abstract “innovation” reached a critical threshold due to population growth, a “phase change” occurred, analogous to water boiling in a kettle on a stove. It's a good analogy, but it doesn’t provide a lot of explanatory value:

A glass kettle is placed on a hot stove. Soon the water within begins to heat up. Looking at the surface of the water, it is hard to detect any change: the water appears peaceful as, at first, the gradual rise in temperature has no visible effects. This calm, however, is deceptive. As the water's molecules absorb heat energy and the intermolecular attractive forces diminish, they are moving ever more rapidly until, past a critical point, the water dramatically changes state—from a liquid to a gas. The water undergoes a sudden phase transition. Not all the water molecules in the kettle convert to a gaseous state at once, but the process eventually sweeps them all away, and the properties and appearance of the water molecules that started off in the kettle are soon entirely transformed.

In the past two centuries, humankind experienced a similar phase transition. Like the conversion of the water in the kettle from a liquid to a gas, it was the result of a process that intensified, invisibly, beneath the surface, throughout the hundreds of thousands of years of economic organization. The transition in state from stagnation to growth appears to have been dramatic and sudden—and indeed it was—but...the fundamental triggers of this transformation were operating from the emergence of the human species, gaining momentum over the entire course of our history. Furthermore, just as some water molecules in the kettle transform to a gaseous state before others, humanity's phase transition occurred at different times across the globe, generating previously inconceivable levels of inequality between the countries that underwent the phase transition relatively early and those that remained trapped for longer. (pp. 43-44)

This is actually quite a good analogy for the suddenness of the change, but Galor underplays the most significant part of this process: the addition of energy to the kettle! It is the addition of energy to the kettle that makes it boil, as the molecules become agitated and bump against each other faster and faster as your primary school teacher explained to you years ago.

In this analogy, the energy added to the kettle is the massive amounts of fossil carbon added to human economies—coal, oil, and natural gas. The molecules are people, and the agitation is the social change brought about by adding almost unlimited quantities of energy to human social systems. Finally, the sudden phase transition from liquid to gas mirrors the Great Acceleration seen during the long twentieth century.

Galor also forgets that once the energy is removed from the kettle, the water does not continue boiling indefinitely—it goes back to being water. The same could be said for what will happen when energy eventually declines or is gradually removed from the economy.

The Alternative View

In the past, all work was necessarily physical, based on human and animal labor. The only way to accomplish more work, then, was to breed more people or animals, which, in turn, required more resources per capita such as food and space, minimizing the gains from the additional output (there were a few exceptions, such as harnessing wind and water power, but these were limited).

But after the Industrial Revolution and the invention of heat engines, you could have machines powered by fossil fuels provide orders of magnitude more labor than ever before without breeding more animals or people. This alone explains why industrial growth was qualitatively different than agrarian growth, and why economic gains were not immediately offset by population growth like before.

On page 82, Galor reprints an advertisement for a tractor from 1921. He cites this as proof of his thesis that it was the need for investment in more education that ended child labor and led to lower birth rates.

A fascinating illustration of the perception of the impact of technology on child labor at the time is reflected in a tractor advertisement from 1921. In order to persuade farmers to purchase a tractor, marketers emphasized the growing importance of human capital. Their campaign stressed that the main benefit of the new technology was the workforce it saved, allowing farmers to send their children to school even during the spring—the busiest season of the agricultural year. Interestingly, the advertisers emphasized the importance of human capital ‘in all walks of life, including farming’. Perhaps they were trying to allay American farmers' concerns that their educated children would choose to work in the booming industrial sector instead of staying on the family farm. (pp. 81-83)

But Galor draws the wrong conclusion from this advertisement. It is the presence of a fossil fuel-powered tractor that more efficiently does the work of many men which allows the farmer to give his son an education, and not some abstract desire for “human capital.” Without the benefit of that “energy slave,” going off to the city for an education would not be feasible. The “booming industrial sector” he mentions was also made possible by fossil fuels. Finally, no matter how many children the farmer has, they can’t compete with the power of a single tractor. Plus, a tractor only needs to be fed oil, rather than having to feed a bunch of additional hungry mouths (although rural families still did tend to be quite large).

I suspect that what really was the initial impetus for lower birth rates was simply the migration of people from the fields and farms to towns and cities. We see this dynamic at work even today. On the farm, more children equals more labor, and families are largely self-sufficient. When you move to the city and depend on wage labor to survive, children become an expense rather than a benefit. They are not, by-and-large self sufficient, and they do not increase the productivity of your farm because you no longer have one. Children become more like parasites—you need to feed, clothe, and house them in a city where employment and living space are at a premium, so it makes sense that people had fewer of them as a result of this migration. Galor perfunctorily notes this, but quickly moves on. I doubt couples were as conscious or as calculating about the number of offspring they had as Galor implies. He cites no evidence for this mentality, and instead offers a fictionalized account of three families in three different time periods to illustrate his human capital theory (pp. 94-98).

We know that in Great Britain, employment in the agricultural sector declined rapidly during this time thanks to the British Agricultural Revolution. These were innovations like seed drills, manuring, improved selective breeding techniques, and four-field crop rotation, among others. In addition, Britain's climate makes its agricultural productivity lower than the continent, however, its climate is ideally suited for pasturage. Because of this, Britain became a major supplier of wool to Europe during the Middle Ages. Sheep raising takes less labor than agriculture, which was another reason why the number of people working in the agricultural sector was lower than in continental Europe. As a consequence, wool production was more profitable for landlords, so they often kicked farmers off the land leading to the remark that Britain was where sheep devoured men rather than the reverse.

In fact, historians generally believe that the British Agricultural Revolution enabled the rise of industrial capitalism in the first place; and, absent that, industrialism could never have taken off. If everyone needed to toil in the fields all day to provide enough food to feed the population, you could not have sufficient employees required to work in the mines, furnaces, workshops and factories—the nation would have starved. Plus, Britain could import grain from abroad to feed those industrial workers, paid for by exports—something not possible in other societies. Due to the increased agricultural productivity of the British Agricultural Revolution, people no longer employed in the agricultural sector could migrate to towns and cities and become the footloose urban proletariat of the Industrial Revolution, and this meant that they necessarily had fewer children as a result.

Curiously, Galor does not mention the British Agricultural Revolution at all in his historical analysis, despite it being featured prominently in historians' accounts of capitalism's rise and development3.

This is considered to be a reason why industrialism could never have taken off in China, despite its long lead in technological innovation. China's huge population meant that its people lived much closer to the margins, so it needed everyone to work in the fields to ensure that its huge population remained fed and didn't revolt. On average, Chinese cities were smaller and less numerous than European ones (Peking excepted). Thus, there couldn't have been enough labor for an industrial sector to take off—the workers would have starved. And China's insularity meant it could not resort to importing grain the way England could.

Paradoxically, it was England's lower agricultural productivity and relative backwardness and isolation that made it ideally suited for an industrial revolution compared to bigger, richer societies. Plus the fact that its coal was conveniently located near the sea (it was originally called “sea coal” as opposed to “charcoal”) allowing it to be shipped around the island as needed for industry before there were railroads. China’s coal, by contrast, was situated in remote, landlocked locations.

Political conditions mattered, too. England's monarchy was weak but its government was strong—strong enough to advance the interests of landlords and industrialists and quell revolt. England's leadership was oligarchical, with deep class divisions between those who owned the land and those who worked it dating from the Norman Conquest. This allowed wrenching and brutal social changes to be pushed through—changes necessary for industrialism to happen—that would have torn other societies apart. In other parts of Europe, for example, people owned the farms they lived on and weren't eager to leave voluntarily and be herded into filthy, overcrowded slums and hellish factories and mines. Emigration was also an option for the losers in this process which was not possible for societies like China, or in other places like Africa or the Middle East who would have likely revolted (as the Luddites and others tried to do).

As for lower reproductive rates, is it really that surprising? It's true that reproductive rates were high throughout the agrarian era, but this was due to high infant mortality. Hunter-gatherers tend to not have more children than their landbase can support. In fact, it seems like population rates were fairly stable throughout the hunter-gatherer era, so Malthus's notion that we will inevitably breed like locusts and strip bare our natural habitat is contradicted by the evidence. Native American cultures, for example—after an initial dieoff of large animals due to overhunting—managed to live sustainably in many places for thousands of years without outstripping their natural habitat. Even though there were exceptions, they seem not to have caused the massive suffering that Malthus assumed it would—people simply moved on and adopted alternative forms of subsistence. Like any organism, we are capable of adjusting our breeding strategy based on environmental conditions.

What caused our reproductive rates to skyrocket during the agrarian era was a number of intersecting forces. Agriculture caused people to become sedentary, whereas it's harder to have lots of children when you are nomadic. Agriculture artificially inflated the food supply, including foods that can be fed to young children, so the space between weaning decreased as children could be fed other foods. Sedentism and animal husbandry led to new diseases, including zoonotic diseases, which spiked the infant mortality rate causing elevated birth rates as we’ve seen. Having more children meant more workers for farmers and horticulturalists, and consequently greater output—something not as beneficial for hunter-gatherers who live off the land. Finally, conflict between societies favored larger societies over smaller ones, so societies which had elevated birth rates tended to conquer or assimilate those that did not invest in having large numbers of children.

Clearly, those factors no longer apply. Most of us don't work on farms anymore; we have antibiotics; bigger armies are less useful in mechanized conflicts; and patriarchy has been supplanted by democracies (for now). Essentially, Galor's declining birth rate was a regression to our “natural” levels of reproduction rather than the artificially elevated levels of the preceding agrarian era arising from infant mortality, patriarchy, the need for stoop labor, and defense against aggressors. Education had little to do with it.

Galor gives his thesis the grandiose name “Unified Growth Theory,” and claims that it provides an explanation for all of economic history to date. As we've seen, I think this is wrong on several counts:

1.) The "phase transition" he describes wasn't caused by innovation in the abstract, but by the addition of massive amounts of energy to the global economy in the form of fossil fuels which could be harnessed by machines to do work leading to the development of an industrial economy. This was the first time in history that the economy could expand without adding more people or animals. Despite this, the population grew much faster than before due to demographic momentum (something Galor neglects to mention), yet living standards continued to rise.

2.) The resulting drop in birth rates wasn't due to the need for more education. It was initially caused by the removal of workers from agricultural labor and the flight to cities, which began first in Britain enabling industrialism, and then spread from there. Then, the steep drop in infant mortality caused birth rates to fall further. As we saw last time, automation largely eliminated the need for child labor. This allowed children to spend more time in school rather than join the workforce. In industrialized economies, having more children became an economic liability rather than a benefit.

3.) Malthus wasn't wrong. In the long term, his dynamic still applies, it's just that we've been kicking the can down the road throughout the industrial era by drawing down nonrenewable resources like fossil sunlight and fossil water. Fertilizers alone allowed the human race to reach much larger numbers than would be possible without it.

4.) There are reasons to think that we will regress to the “pre-growth” state in the future. According to Bradshaw, even in the event of massive wars, famines and pandemics, population will not decline because the birth rate increases to compensate for higher death rates. Only a severe lack of basic resources has been shown to arrest this dynamic. Just like water transitioning to gas, this “phase transition” may not be permanent.

The second part of Galor’s “Unified Growth Theory” is intended to explain why some countries became rich while others remained poor. There's little original thought here—it's just a collection of theories that have been around a long time. Galor focus on four aspects in particular:

1.) Historical contingencies. For example, as Jared Diamond pointed out, some places had an abundance of domesticable plants and animals giving them a head start in development, while other places like the Americas lacked domesticable animals.

2.) Geography. Europe had a long, fractal coastline, many navigable rivers, and geographical barriers which led to both a plurality of polities and extensive trade networks encouraging economic and social development. China, by contrast, had a lot of interior land area relative to coastline. This led to political centralization, which in turn led to cultural stagnation, while Europe was able to escape this trap. Africa, too, had lots of land relative to coastline and few navigable rivers keeping polities small and isolated, along with tropical diseases such as sleeping sickness hindering development.

3.) Culture: Galor talks about how the religious beliefs of Jews and Protestants led to higher rates of literacy among these populations. While literacy was initially encouraged in order to read holy books, high rates of literacy translated into bigger economic gains later on. Places that had a lot of high-yield crops and a stable climate tended to develop a more future-oriented mindset and lower loss-aversion which enabled economic growth, and so on.

4.) Diversity. Not just ethnic, but ideological diversity. Galor sees diverse societies as more innovative, although he notes that too much can hinder cooperation. Successful societies, Galor says, have a “Goldilocks” level of diversity—not too much, not to little.

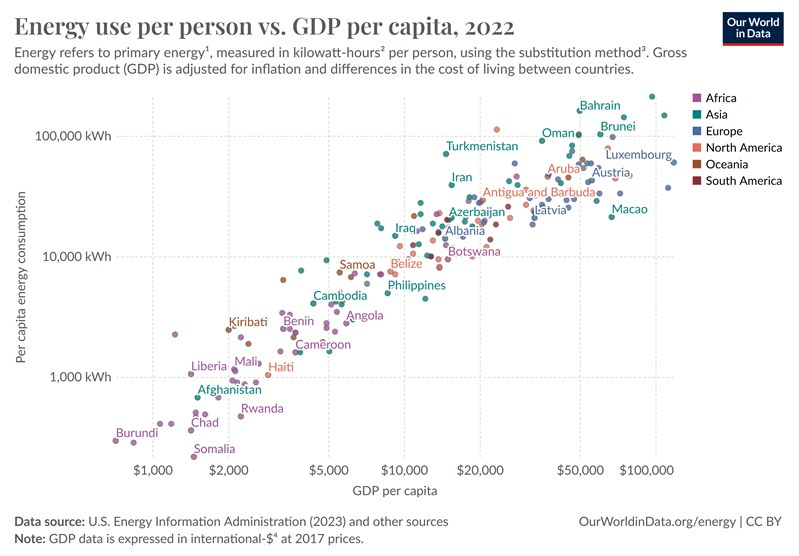

Here, too, taking energy into account would have helped this thesis. There's no such thing as a rich country with low per capita energy usage, and, in fact, energy use per capita and the economic growth are tightly correlated. This also explains differences in wealth, as poor countries tend to use little energy per capita and still depend on physical labor, hence their higher birth rates. It's notable that these countries, despite their desire for more human capital, have difficulty educating their populations, and there is not that much for those newly educated people to do except go abroad to developed countries which already use more energy per capita.

Galor says little about colonialism, and Immanuel Wallerstein's core-periphery model provides a more intellectually complete framework for explaining differences in income and development in my opinion. Galor also says little about the effects of climate change, instead offering the old canard that as countries get richer they tend to pollute less—true for already developed countries but not accurate for the world as a whole.

The Journey of Humanity reminds me of another “big history” book written by an Israeli scholar: Yuval Noah Harari's Sapiens. Like that book, there’s little new or original in Galor's Unified Growth Theory, despite its grandiloquent name. However, like that book, it covers a lot of history and aggregates a massive amount of ideas and data in a very digestible and easy-to-read format, although more focused on economics rather than sociology like Harari’s book. For all its flaws, it does provide a good summary of a lot of modern ideas about growth and the causes of international wealth and poverty, as well of an overview of a lot of economic changes that have occurred.

For me, the most important part of the book was its description of the social changes that have occurred thanks to industrialization, which have become more pronounced as we move into an era where education requirements keep going up while birth rates keep declining and living standards appear to have stagnated leading to a worldwide political backlash. Understanding how and why these changes unfolded in the long run is important and valuable, and offers a hint of what our future might look like.

Ultimately, there is a "Unified Growth Theory" which explains all of the things Galor is trying to explain. But it's understanding the role of energy in human systems, which offers a more comprehensive and accurate picture than Galor's thesis, which—although accuate in some places—falls short.

https://www.thegreatsimplification.com/episode/136-corey-bradshaw. Hat tip reader Jan Andrew Bloxham.

For example, The Relentless Revolution by Joyce Appleby.

Lots to say about this, but for now I'll just bring up something about birthdates that's been rattling around in my head for a while: why does the demographic transition model assume that the replacement rate is some sort of natural equilibrium? It seems totally unjustified, as there isn't any personal feedback between peoples individual choices to have a certain number of children and mass society's population growth rate. It's the exact opposite situation as among hunter-gatherers.