Ultrasociety by Peter Turchin - Review (Part 1)

How did human societies become massive engines of cooperation?

I wanted to review Ultrasociety by Peter Turchin because it talks about many of the same themes we discussed in Mark Moffett's The Human Swarm—specifically how human groups have combined to form larger and larger societies over time.

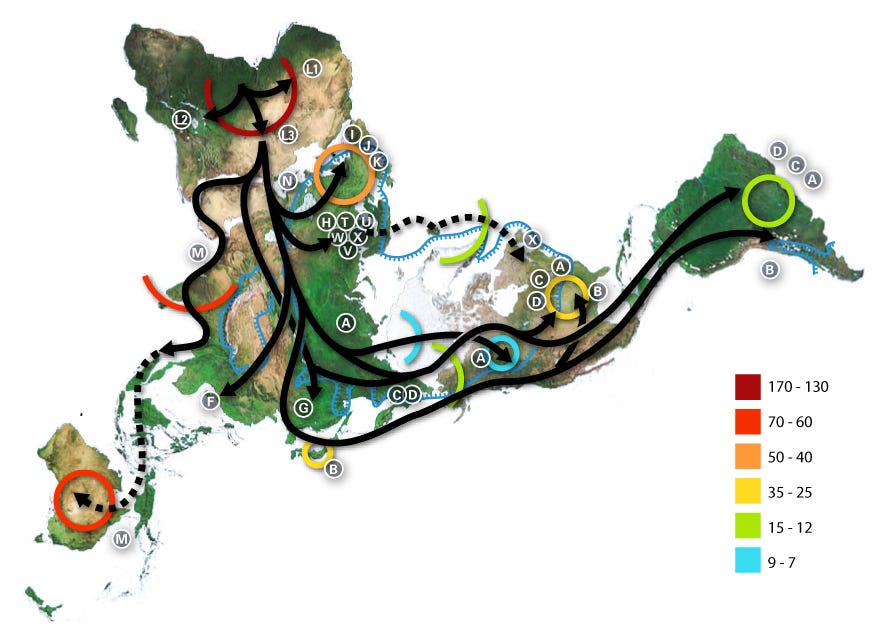

As we saw in that book, it was the merging of discrete societies that led to the explosive growth of polities over the last several thousand years, and not the organic growth of individual societies which brought it about. We live in totally different social and ethnic groups today than our ancestors did ten or twenty thousand years ago. In fact, some ethnic groups which were genetically quite distinct 25,000 years ago no longer exist in any form today—a fact that can be determined by examining the genetics of ancient skeletons (something we'll discuss in more detail when I review David Reich's book Who We Are and How We Got Here).

Who We Are And How We Got Here - Part One - Introduction

Img. Source: CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=227326 The vast majority of human history took place long before the written word was invented. This period encompasses the time from humans left first the African continent some 50,000 years ago and spread across the globe to the when the first civilizations began roughly 5,000 y…

Moffett did a good job of articulating what happened, but he doesn't really explain why this occurred. Why, when the natural tendency for human groups is to break apart over a certain size, did polities suddenly become larger and larger over the last several thousand years? Both our brains and our language seem to be suited for living in smaller groups of people. In other words, we seem to be hard-wired on some level for permanent fissioning above a certain group size. Hunter-gatherer and tribal societies exhibit this dynamic. Look at how easily languages diverge, for instance. Before mass communication, even neighboring villages could have their own distinctive dialect.

Author Robert Wright summarizes this process on an episode of Tangentially Speaking:

[50:20] "Life has been on this planet for three and a half billion years. It has reached higher and higher levels of organization. It reached the level of the simple cell—the prokaryotic cell; then the complex cell—the eukaryotic cell. Then those cells got together into multi-celled organisms. Then those organisms got together into societies of [multicellular] organisms. So you've ascended several levels of organization."

"And then in our species, although we're not the only species with what you could call cultural evolution—that is to say, the intergenerational transmission of information that's not genetic, and it's sort of selective retention. We have a big robust version of cultural evolution: technology; political ideas; religious ideas, the whole thing. And that evolutionary process has carried the level of organization of our species from the level of hunter-gatherer society 20,000 years ago; to chiefdoms, city-states, and so on. And now we're on the verge of forming a global community. That's at least now technologically possible—a relatively harmonious global community."

Tangentially Speaking episode 469: Robert Wright

As societies have gotten bigger, they've been able to execute larger and larger projects. Ancient peoples built Göbekli Tepe, Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids. Toward the end of the Twentieth Century we launched the International Space Station and are attempting to develop a fusion reactor to replace fossil fuels on an international level. Turchin estimates the number of man-hours required to execute each of these projects to quantify just how many orders of magnitude our ability to cooperate has scaled up over the course of history (whether or not human well-being has increased as well is, of course, another matter).

It cries out for an explanation.

In Ultrasociety Peter Turchin offers his explanation. It's formal name is Cultural Multilevel Selection Theory (CMST) and the book is largely an articulation of this model. (Note: it’s only available as an e-book, so no page numbers, sorry! Blockquotes and italics are from the book unless noted otherwise. Emphasis mine unless noted otherwise.)

This book is about ultrasociality—the ability of human beings to cooperate in very large groups of strangers, groups ranging from towns and cities to whole nations, and beyond.

Turchin is best known for his theory of Secular Cycles, and has become somewhat notable of late for predicting a zenith in political chaos in the United States beginning in the year 2020—a prediction he made about ten years ago.

I think the best way to understand the theory is to look at each of these concepts in isolation, and then bring them together to see how they form a cogent hypothesis which explains (in his view) the metastatic growth of human societies during the last ten thousand years of human history.

Let's start with cultural.

1. Culture

What, exactly, is culture?

Culture can be defined as "socially transmitted information that, together with genes and environment, shapes people’s behavior." Another way of describing this is shared social learning. As Wright notes above, it is considered to be information that is transferred down through time through means other than genetics.

What are “cultural traits”? Culture is understood very broadly as any kind of socially transmitted information. Thus, information about edible berries and mushrooms that parents and other experienced elders transmit to youngsters is part of culture. Culture also includes knowledge of how to make tools; stories and songs; dance and rituals; and “norms”—socially transmitted rules of behavior. Basically, any kind of information that is passed between members of a society qualifies under this definition.

It used to be thought that human beings were the only animals who possessed culture. Subsequent research has shown this to be false. For example, careful observation has shown that behaviors including tool use, grooming and courtship differ between different groups of chimpanzees. Clearly such differences in behavior are not caused solely by genetics.

It's not just primates—migratory routes in birds other animals have been shown to be socially transmitted to some degree. Many birdsongs have distinctive "dialects" even within the same species indicating that they are culturally transmitted behaviors. Recently even fish and fruit flies have been shown to demonstrate aspects of cultural behavior.

Culture was once considered the patented property of human beings: We have the art, science, music and online shopping; animals have the instinct, imprinting and hard-wired responses. But that dismissive attitude toward nonhuman minds turns out to be more deeply misguided with every new finding of animal wit or whimsy: Culture, as many biologists now understand it, is much bigger than we are.

“If you define culture as a set of behaviors shared by a group and transmitted through the group by social learning, then you find that it’s widespread in the animal kingdom,” said Andrew Whiten, a psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland... “You see it from primates and cetaceans, to birds and fish, and now we even find it in insects.”

Culture “is another inheritance mechanism, like genes,” Hal Whitehead of Dalhousie University, who studies culture in whales, said. “It’s another way that information can flow through a population.” But culture has distinct advantages over DNA when it comes to the pace and direction of information trafficking. Whereas genetic information can only move vertically, from parent to offspring, cultural information can flow vertically and horizontally: old to young, young to old, peer to peer, no bloodlines required. Genes lumber, but culture soars...

Meet the Other Social Influencers of the Animal Kingdom (New York Times)

Humans are not unique or special, then, in possessing culture. But we are unique in the extent to which we rely on it for our survival and the rate at which we innovate. While it takes a long time for genetic mutations to spread throughout an entire population via natural selection, cultural changes can take place very rapidly due to human behavioral flexibility. The other important aspect of culture is that it causes the members of a society to behave in similar ways, as David Deutsch describes in The Beginning of Infinity:

A culture is a set of ideas that cause their holders to behave alike in some ways. By 'idea' I mean any information that can be stored in people's brains and can affect their behavior.

Thus the shared values of a nation, the ability to communicate in a particular language, the shared knowledge of an academic discipline and the appreciation of a musical style are all, in this sense, 'sets of ideas' that define cultures. Many of them are inexplicit; in fact all ideas have some inexplicit component, since even our knowledge of the meanings of words is held largely inexplicitly in our minds...

The world's major cultures—including nations, languages, philosophical and artistic movements, social traditions and religions—have been created incrementally over hundreds or even thousands of years. Most of the ideas that define them, including the inexplicit ones, have a long history of being passed from one person to another.

What this means is that all the members of a particular culture tend to converge on the same behaviors over time: "What imitation does, then, is make members of the same group more similar to each other. In other words, it destroys within-group variation. At the same time, different groups are likely to converge on very different sets of behaviors, so that variation between groups increases." A single person in isolation, by definition, cannot have a culture—it is exclusively a characteristic of groups.

As Wright notes above, different aspects of culture tend to be selectively retained. That is, some cultural behaviors get passed through time down while others go extinct. Cultural behaviors also change due to innovation and randomness. This process of incremental change has been likened to Darwinian natural selection. Biologist E.O. Wilson used the term culturegen (akin to pathogen) to describe aspects of culture which are selectively transmitted down through time, but by far the more popular term is Richard Dawkins’ coinage of a meme.

Despite surface similarities, however, culture cannot be depicted as a discrete series of alternatives. Different cultures vary greatly across a spectrum of variables such as bellicosity, egalitarianism, cooperativeness, religiosity, and so forth: "Human societies vary along many dimensions—scale of cooperation, degree of economic specialization and division of labor, forms of governance, levels of literacy and urbanization, and so on." But there are similarities as David Deutsch describes:

People modify cultural ideas in their minds, and sometimes they pass on the modified version. Inevitably, there are unintentional modifications as well, partly because of straightforward error, and partly because inexplicit ideas are hard to convey accurately: there is no way to download them directly from one brain to another like computer programs. Even native speakers of a language will not give identical definitions of every word. So it can be rarely, if ever, that two people hold precisely the same cultural idea in their minds....Thus, a culture is in practice defined not by a set of strictly identical memes, but by a set of variants that cause slightly different characteristic behaviors.

The idea that cultures evolve is at least as old as that of evolution in biology. But most attempts to understand how they evolve have been based on misunderstandings of evolution...although biological and cultural evolution are described by the same underlying theory, the mechanisms of transmission, variation and selection are all very different. That makes the resulting 'natural histories' very different too. There is no close cultural analogue of a species, or of an organism, or a cell, or of sexual or asexual reproduction. Genes and memes are about as different as can be at the level of mechanisms, and of outcomes: they are similar only at the lowest level of explanation, where they are both replicators that embody knowledge and are therefore conditioned by the same fundamental principles...

Many archaeologists have increasingly turned to the mechanisms of cultural evolution to explain how human societies and cultural practices have developed over time. This is well articulated by archaeologist Stephen Shennan on an episode of Tides of History:

[19:22] "What I mean [by cultural evolution] is something very specific that is taken from the ideas of the anthropologists Rob Boyd and Pete Richerson. Their definition of culture is 'information capable of affecting people's behavior that they acquire from other members of their species through things like teaching and imitation.' So that's the definition of culture."

"For a theory of culture to be evolutionary in Darwin's sense of the term, which is 'descent with modification', it requires, first of all, mechanisms for generating variation. In biology you have mutations; in culture you have innovations. It also needs a mechanism for transmitting that variation through time. In biology that's reproduction by which the genes are passed on. But in culture it's social learning. So social leaning is the mechanism for creating cultural traditions."

"And then you need some kind of mechanism so that some of those things that are transmitted increase in frequency and others decrease and disappear. There can be lots of different kinds of mechanisms for culture—a much wider variety than for natural selection in biology..."

Professor Shennan is particularly concerned with the transition from foraging to farming, as he is the author of The First Farmers of Europe: An Evolutionary Perspective. But similar mechanisms can be used to explain all kinds of social developments such as living in cities, trade patterns, technological development, political structures, and so forth.

As we'll see in a bit, what Professor Turchin is looking for is the origin of cooperation in various societies over the course of human history, especially cooperation between unrelated groups of people in large-scale, complex societies. That’s what at the core of Ultrasociety. Cooperation and social trust, he argues, vary in degree between different societies along a spectrum, and their levels change over time:

Is [cooperation] a cultural trait? The key question is whether this attitude is socially transmitted or individually learned...Periodic social surveys indicate that generalized trust behaves just as we would expect a cultural trait to behave. National-level studies show that each surveyed population is characterized by a mixture of people holding different beliefs about whether others can be trusted. The relative proportions of different beliefs are quite stable—but they do change, given enough time. In other words, this cultural trait evolves. And that, remember, is all evolution is. There doesn’t have to be “progress.”

Next let's examine what is meant by multilevel.

2. Multilevel

In my series of posts on The Human Swarm, I noted that humans live in multilevel societies. Each level of the social hierarchy performs some sort of complimentary function for its members: defense, provisioning, sexual reproduction, child rearing, and so on. Each level is nested in another like a set of Russian dolls. Multilevel societies appear to be a very common evolutionary strategy because lots of animals live in them including other closely-related primates such as baboons, chimpanzees and bonobos.

Multilevel selection theory argues that natural selection does not just operate on the level of individuals or genes, but rather, natural selection is operating on all levels of the biological hierarchy simultaneously. In other words, multilevel selection indicates that Darwinian natural selection operates not only on the level of individual organisms, but also on the level of groups. Sometimes this concept is referred to as group selection theory.

It used to be thought that natural selection acted only on the level of individual organisms. Specimens which were a better fit for their natural environment would have greater success at survival and reproduction, the thinking went, compared to other individuals who were not as good a fit.

Note that from a Darwinian standpoint, a “fit” individual is not in any way "superior" to one that is less fit—those are value judgements imposed by human beings. There is no “better” or worse” when it comes to natural selection. The evolutionary process is blind—it is not heading toward some sort of "end goal" in humans nor in any other species. Yeti crabs are far more "fit" than human beings on deep sea hydrothermal vents, for example. A square peg is less "fit" than a round one only because of the shape of the hole. That is to say, fitness depends on the environmental conditions.

Yet we often see instances where, on the surface at least, individual animals appear to reduce their own reproductive "fitness" all the time. They share resources with others. They sometimes give away food. They cooperate. They fight alongside one another. Sometimes they even die for one another. Bees will, for example, sacrifice themselves to protect the hive. Other insects such as ants engage in similar behaviors. How can such behaviors be explained according to the Darwinian natural selection model which theoretically revolves around individual organisms maximizing their own reproductive fitness? For a long time this question vexed biologists including Darwin himself.

Eventually, the favored explanation became the one offered by biologist Richard Dawkins in his 1977 book The Selfish Gene. The main idea was that natural selection primarily operated on the level of the gene rather than on the level of individual organisms or species of animals.

Dawkins argued that genes were "selfish" in the sense that they only cared about their own survival and reproduction, and not the survival and reproduction of the individuals who happened to be their carriers. While on the surface it looked like certain behaviors were an obvious handicap to survival and reproduction, from the "gene's eye view" they were actually the opposite. While detrimental to the survival of any particular individual, these behaviors made certain genes more likely to survive and proliferate in the populations which harbored them. In other words, the primary locus of competition was not between different species, or among members of the same species, but between variants of genes within species.

This insight led to the development of kin selection theory, which argued that individual organisms would willingly sacrifice themselves for close relatives because their relatives shared a large proportion of the same genetic material. In other words, altruistic behaviors could be beneficial for the survival of certain specific genes, even if they reduced the fitness of any specific individual. That was what made the gene "selfish," and not that genes necessarily led to selfish behavior, or that genes for selfishness were inherently more adaptive. It was ultimately the genes' survival and replication that mattered in the arena of natural selection, argued Dawkins, and not individual organisms.

This conclusion meant that we would be much more willing to sacrifice ourselves for close relatives than we would for distant strangers. Expressing this cold mathematical logic, the biologist J.B.S. Haldane supposedly remarked that he was “prepared to lay down his life for eight cousins or two brothers.” In other words, altruism was no more than a thinly veiled form of nepotism. Haldane and other biologists emphasized that we did not rationally make such calculations, but rather that we were simply meat puppets unconsciously acting according to the directives of the packets of DNA who use us to propagate themselves. Mathematical models were developed showing how certain genes could survive and proliferate even if some of the individuals carrying them engaged in what appeared on the surface to be self-sacrificial behaviors.

Then in the 1970s an American mathematician and economist named George R. Price derived a series of equations which appeared to demonstrate how altruistic traits could arise due to intense selection pressure between groups. He was motivated to develop these equations because he had become obsessed with discovering the origin of altruism in human beings after converting to Christianity and giving away all his possessions1 . While attempting to find the mathematical basis for kin selection, he inadvertently discovered a mechanism describing how altruistic traits could emerge even in groups of unrelated individuals.

These equations—known as the Price Equations—eventually led to the development of the modern version of group selection theory, which argued that selection pressure on groups could lead to different outcomes than selection pressures working only at the level of individuals or genetic variants. This theory was most recently championed by the biologists E.O. Wilson and David Sloan Wilson (no relation) who summed it up as, "Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary.2"

But some commentary might be helpful in this instance, so here's some from Dr. Turchin:

To illustrate this idea, let us consider a personal trait like courage. Warriors who place themselves in the front lines during a battle and confront the enemy bravely are in much greater danger of being wounded or killed than cowards who hang back and run away at the first sign of danger.

A naïve evolutionary argument would suggest that, in each generation, more brave youths would be killed than cowardly ones, meaning that they fail to marry and leave children. As a result, each successive generation will have fewer courageous men, and eventually this trait will be eliminated by natural selection.

But we can think about this question in a different way. As Charles Darwin himself noted, tribes with many courageous warriors will be much more likely to win battles and wars against tribes with many cowards. Because defeat can have dire consequences for the tribe, up to and including genocide, we would expect that courageous behavior, on the contrary, would increase.

Which of these arguments is the correct one? According to the theory of Multilevel Selection, neither. Or, a better way to put it, both provide incomplete answers.

Natural selection can simultaneously act on individuals within groups, and on whole groups. Within each tribe, cowards do better than brave men, on average increasing every generation. But at the same time, cowardly tribes are eliminated by courageous ones.

Which of these processes will be stronger depends on many details: just how great is the cost of bravery? How frequent is warfare and what are the consequences of defeat? How frequently are defeated tribes eliminated? The frequency of brave types will decrease or increase depending on which selective force is greater, the one acting on individuals or the one acting on groups.

While we often tend to assume that being a selfish asshole is ideal for individual survival (especially in the individualistic United States), groups that consist only or predominantly of selfish assholes will be outcompeted by people willing and able to cooperate with others and sacrifice to accomplish some sort of collective goal. In order to determine which type of behavior will prevail—selfish or altruistic—Turchin gives us a very simplified version of the Price Equation which, he assures us, is the only math in the book:

The simplified equation quantifies the weights of the relative pressures on different levels of a multilevel society in order to determine which unit of selection in the evolutionary hierarchy will prevail—the individual or the group. This will vary over time and is dependent on a number of factors.

Because cultural traits have consequences, they are subject to selection. One of the most important insights from the theory of Cultural Multilevel Selection is that selective pressures affecting frequencies of cultural traits can work in opposite directions, depending on whether we consider selection on individuals or on social groups...different forms of competition can have very different consequences for cooperation. It all depends on the level—whether it is competition between individuals within a team, or competition between teams. This is one of the most important insights from the theory of multilevel selection...

Put simply, if there is intense competitive pressure between groups, then the group will be the primary unit of selection. In circumstances where the competition between groups is less frequent and intense, maximizing individual fitness (i.e. being a selfish asshole) might be the winning strategy. This is obviously an oversimplification. Turchin works out some of these processes in more detail but I'm going to skip over that—check out the book if you want to learn more.

To say that group selection is controversial would be an understatement. Most biologists today still refuse to accept it, and many prominent biologists—notably Richard Dawkins and Steven Pinker—maintain that group selection simply does not occur. Turchin contends that, while the naïve group selection of early biologists was indeed shown to be wrong, it is still valid when it comes to the evolution of cultural traits in social animals where competition between groups is especially frequent and intense:

Early proponents of group selection did not understand the importance of variation between groups, nor how difficult it is to maintain in the face of constant migration. They weren’t stupid; it’s just that the mathematical theory had not yet been developed to make this point clear.

Nevertheless, critics such as G. C. Williams and Richard Dawkins were quite correct to point out the errors of the naïve group selectionists, such as V. C. Wynn-Edwards and Konrad Lorenz. Numerous approaches to modeling genetic group selection have shown it to require rather special circumstances that rarely arise in the natural world.

However, the critics also erred when they included human beings in their sweeping rejection of group selection. Humans are very unusual animals. We have huge brains and are capable of remarkable mental feats. We also have culture. And that makes a huge difference.

It should be noted that, while natural selection is obviously not limited to Homo sapiens (or even to living things—hence the notion of Universal Darwinism), this kind of intense cultural competition between different groups is unique to Homo sapiens. Other animals either rely less on culturally transmitted behaviors, have less cohesive social groups, or do not engage in such regular head-to-head competition within groups. The only exceptions might be the social insects like ants, bees and termites which may be why they display so many behaviors which are superficially similar to human beings (war, slavery, genocide, extensive niche construction, cooperative behavior, altruism, and so on). E.O. Wilson controversially argues that humans and ants are both eusocial species (eu- meaning "true"). As Tuchin notes, “Such a multilevel nature of organization of economic and social life has profound consequences for the evolution of human societies—just how profound we are only now beginning to understand, thanks to Cultural Evolution.”

Nevertheless, Dawkins, Pinker, and other biologists continue to insist that behaviors like altruism and cooperation are merely by-products of kin selection—end of story. Turchin—himself trained as a biologist and zoologist—is highly skeptical of this claim. He points out that kin selection often impairs large-scale cooperation rather than encourages it. Favoring our own close friends and relatives is known as nepotism and cronyism, and these things have long been recognized by political scientists as impediments to the formation of large-scale cooperative societies. For example, Francis Fukuyama has argued that large-scale complex socialites can only form once kinship is taken out of politics—a process he refers to as depatrimonialization.

In other words, all the complex, intricate arrangements our ultrasocieties employ to sustain cooperation, maintain internal peace and suppress crime, organize efficient production and delivery of all kinds of goods, and achieve spectacular feats, such as lifting the International Space Station into the Earth’s orbit—all of that is simply a “by-product” of natural selection in ancestral times, when we lived in small groups of relatives and friends.

The idea that modern, complex societies are a by-product of evolution during the Pleistocene is as far-fetched as the proposition that our remarkably efficient, intricately constructed bodies are by-products of natural selection acting on our distant ancestors, single-cell organisms, three billion years ago...

[K]in-selection theory does not explain cooperation in groups of genetically unrelated people. The gene-centric view does not help us understand why a soldier would fall on a grenade to save his buddies at the expense of his own life. And it doesn’t help us to understand how huge, cooperative human societies evolved. The Selfish Gene is, in many ways, a brilliant book. Yet it fails utterly to explain one thing: the evolution of cooperation in human beings.

It' is important to note that, strictly speaking, it is the existence of cooperation and not simply altruism that we are trying to explain. Since cooperation can be mutually beneficial to both parties, unlike altruism, it does not require an explanation at odds with maximizing individual or group fitness.

It's also important to note that Turchin is seeking an explanation for these behaviors rooted primarily in cultural evolution, and not in biological evolution. Cultural evolution operates on much shorter timescales than does biological evolution. It also operates via different mechanisms. Therefore, even if one refuses to accept group selection for biological traits, I seen no reason why one can't still accept it for the evolution of cultural traits. As Turchin himself points out, "It is much easier for Multilevel Selection to operate on cultural variants than to do so on genes." And both genes and culture affect individual behavior and interact with each other in complex ways (as described by the concept of gene-culture coevolution3).

By now I hope you have a better understanding about what is meant by cultural and multilevel. But a number of questions still remain.

Which cultural traits were being selected for? And what was the mechanism by which successful traits were propagated while other, less successful ones were eliminated?

It should be obvious by now that the most important cultural trait being selected for in Turchin's formulation was cooperation, otherwise known as generalized social trust. And the selection mechanism, he contends, was existential head-to-head competition between rival societies in the form of warfare. That's where the various strands of the theory finally come together.

We’ll talk about that next time.

Price moved from the U.S. to London. His all-consuming obsession with discovering the roots of altruism led to him giving away all his possessions and devoting his life to selflessly assisting the poor and downtrodden. He let alcoholics stay in his flat and steal all his money while he slept in his office, for example. He eventually became so depressed and discouraged that he killed himself.

It's a fascinating story. If you're interested, I highly recommend watching this video of a talk by the author of a biography of Price:

This, of course, is a paraphrase of Rabbi Hillel, who articulated the Golden Rule before Jesus: "That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah; the rest is the commentary; go and learn." No doubt Wilson and Wilson intentionally wished to evoke the altruistic sentiments of this quote.