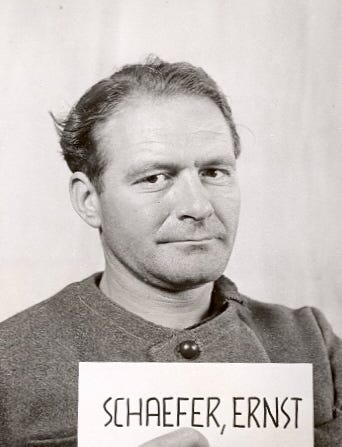

In the definitive book on the Nazi mission to Tibet, Himmler's Crusade, author Christopher Hale relates an odd story. Haupstrumführer Ernst Schäfer, an SS officer, boards the Luxuszüge night express train from Munich to Berlin during the war in 1942. He takes the top bunk in the Schlafwagen. Another passenger, a doctor named Walter Hauck, takes the bottom bunk. During the middle of the night, the train attendants hear a ruckus. Bursting into the cabin, they find the two occupants engaged in an apparent life-and-death struggle, with Schäfer attempting to choke the hapless doctor. They break up the fight. Hauck initiates legal proceedings against Schäfer, but Schäfer's political connections get him off the hook and out of a prison sentence.

Several years earlier, during 1938-39, Ernst Schäfer1 had been the leader of the SS mission to Tibet. It's difficult to know exactly what to take from the above story, but Hale seems to imply that there were some significant demons buried deep down in Schäfer's subconscious from his activities before and during the War.

The Expedition

Schäfer's biography was fairly typical. He was born in Cologne in 1910. His father Hans was an influential Hamburg industrialist. Like many others who figure in our story, Schäfer was interested in the great outdoors and remaining on the fringes of civilization as much as possible from a young age. For Schäfer, this meant developing an obsession with hunting. He entered Göttingen University, graduating with a doctorate in zoology specializing in birds. At this time, being a naturalist basically meant traveling to exotic destinations, shooting as many animals as possible, and hauling their hides and carcasses back to natural history museums all over the world. This was still the age of exploration, with Europeans heading all over the world in search of knowledge combined with adventure.

As a youth in his early twenties, Schäfer had participated in not one, but two expeditions to Central Asia under American auspices, the second one as co-captain. The impression one gets is that Schäfer was not an enthusiastic Nazi, but was extremely ambitious, which led him to join the SS shortly after the Nazis came to power (although he would later claim he joined in 1936).

Eventually he came to the attention of Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Schäfer told Himmler about his desire to lead an elusively German expedition to Tibet, which gelled with Himmler's own peculiar obsessions.

Schäfer had no particular interest in the occult but he was most eager to lead another expedition to Tibet, one that would carry out his own mission of exploring Tibet as a refuge of "syncretic science," which presumed Tibet's environment as a kind of "cradle of mankind," a repository of long-extinct wildlife. According the the German scholar Reinhardt Greve, Schäfer saw himself as not only an SS pioneer and adventurer but also a "prophet of objective science," and "the bearer of the core of German manhood," who must erase the last blank spots from the maps. (Tournament of Shadows, p. 513)

Although Schäfer originally intended the expedition to be independent, the Ahnenerbe would increasingly place their imprimatur on the mission, which caused trouble when it came time to secure the necessary permissions. Despite its connection to the SS, funding for the expedition was raised almost entirely through private donations.

There would be a total of five men on the expedition, all SS officers. Himmler's Crusade makes the most of Bruno Beger, the mission's anthropologist because, as the anthropologist, he was the most intimately connected with the German racial theories of the time which were a major focus of the expedition.

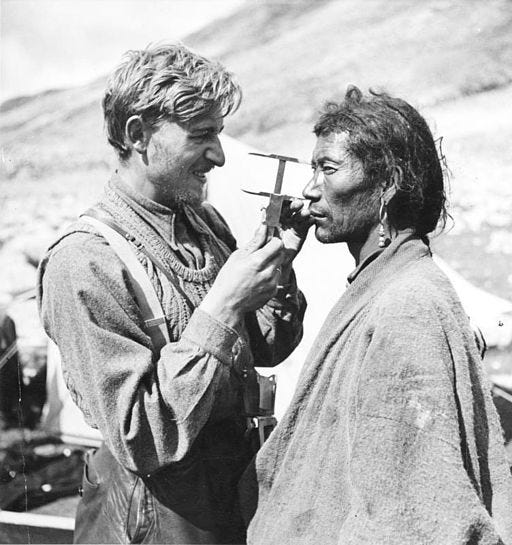

Beger had studied at Jena University under professor Hans F.K. 'Rassen' Günther. Günther had gained his position due to the Party's influence, and had helped develop the Nazi racial theories, which he passed along to his students. Günther believed that physical anthropology was concerned with with “calculable details of body structure,” and that Europeans were a mix of several fundamental races: the Nordic, the Mediterranean, the Dinaric, and so on, whose exact composition could be determined via anthropomorphic measurements. Under his influence, anthropological "research" in Germany consisted of taking people's skull measurements with calipers, consulting eye color charts, and making plaster masks of individuals to determine their racial “typology”. It was the mixing of the Nordic race with inferiors—especially Jews—that threatened German culture according to Günther.

In 1935 Beger applied to join Himmler's elite. Like Schäfer, but for different reasons, Beger would have been an attractive recruit. He was an anthropologist and student of Hans Günther whose world was highly valued by the new rulers of Germany. He was a textbook 'Nordic' specimen, as photographs and the film of Schäfer's expedition demonstrate: tall and blond with chiseled aquiline features...By 1935 his application had been approved, and Beger was an SS Mann. In the same year he joined the Nazi Party, neither an early recruit nor a 'March Violet'—referring to those Germans who ruched to join the party when Hitler had seized power. More significant was the fact that he now made the acquaintance of Dr August Hirt, a doctor devoted to the Nazi cause. Hirt and Beger would together become involved in one of the darkest episodes of German 'science'. (HC, p. 108)

Schäfer, the "famous explorer," personally recruited Beger in 1937 while Beger was still working on his doctoral degree, which consisted of traveling through the Altmärkische and taking cranial measurements of the Dutch-descended inhabitants there to determine their racial background. The remaining expedition members consisted of: Ernst Krause as entomologist, photographer, and film cameraman (the oldest member at 38); Karl Wienert as geophysicist; and Edmund Geer as technical caravan manager.

Himmler's Crusade (HC) relates that Himmler pushed to have the expedition take along an "expert" in the World Ice Theory named Edmund Kiss (which also happens to be a great villain's name). Schäfer saw himself and his colleagues as legitimate scientists, however, and did not wish to taint the expedition by bringing along someone whom he (correctly) perceived as a crank pushing pseudoscientific nonsense. This led to some friction with Himmler, but eventually Schäfer got his way and Kiss stayed behind.

One of the most difficult hurdles was getting permission from the British to enter India given the geopolitical tensions at the time and the mission's clear SS connections. The expedition planned to enter Tibet via India and Sikkim, which were both under British control. At one point Himmler himself intervened and wrote a letter directly to Sir Barry Domvile on their behalf, which opened doors but also raised suspicions. They also needed permission from the Tibetans. Schäfer secretly intended to take a page from Sven Hedin and was prepared to sneak into the Hidden Kingdom if need be.

The expedition set sail in 1938 from the port of Genoa through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea across the Bay of Bengal to Madras, India, and from there by train to Calcutta. From Calcutta, they took cars to the British residency at Gangtok inside the tiny kingdom of Sikkim on the border with Tibet. There they would repeatedly clash with the British political officer residing there, Sir Basil Gould. Gould would later summarize Schäfer's personality as, "interesting, forceful, volatile, scholarly, vain to the point of childishness, disregardful of social convention or the feelings of others, and first and foremost always a Nazi and a politician..." (TOS, p. 513)

The British were highly suspicious of the mission from the start, viewing Schäfer and his comrades as spies as much as scientists. It didn't help that, as the expedition set off in 1938, the Nazi’s official newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter, published an article about the expedition linking it with the Ahnenerbe which was reprinted in Indian newspapers with the more sensationalist headline, "Nazi invasion—Blackguards in India."

In Gangtok the expedition acquired a young Nepalese translator named Kaiser Bahadur Thapa. There are differing stories about how Kaiser got his German-inflected name. Kaiser's father had fought with a Gurkha regiment in France during World War One. Based on the pattern of constellations at the time of his birth, he had to give his son a name starting with the letter 'K'. One story had it that he regarded the Kaiser as a "fellow warrior." Another was that he gave him the name because he came to resent the British and felt that "the enemy of the enemy is my friend." Thapa's parents had both died and he was currently supporting his sisters.

Schäfer and Kaiser would develop a very close, paternalistic relationship. Ten months before the expedition set sail, Schäfer—despite being an expert marksman—had shot his new bride in a hunting accident, killing her. Schäfer wanted to adopt Kaiser as his son and and bring him back to Germany to train as a taxidermist when the expedition ended because, according to him, "he had lost his wife and had nobody." This would be blocked by the British, however.

Soon [Thapa] would be the 'Kaiserling, shy boy and favorite of us all...' He had been to Gangtok High School and was clearly very bright. When he met the Germans, Kaiser was holding down a hundrum job in the Sikkim civil service, twiddling his thumbs in an airless cubby hole, and he longed for adventure. And he knew his worth: He asked Schäfer for a higher salary than anyone else. So impressed was Schäfer that he took him on as a translator without much fuss.

Much later, it would become evident, at least to the British, that Kaiser's Tibetan was poor, but the young man's value to the expedition and to Schäfer himself would far outweigh his failings as a linguist. Schäfer called this 'delicate, handsome, shy, wiry and intelligent' youth 'my selfless, courageous, yes, almost indispensable comrade.' Beger remembers, with some rancour, that Kaiser always knew more about Schäfer's plans in advance than he or Geer ever did. Kaiser alone would be immune from Schäfer's frequent rages, and he would receive most of his attention. (HC, p. 169)

The expedition spent six months wandering around Sikkim. Schäfer enthusiastically shot as many animals as he could. He claimed to discover a previously unknown species—the Schapi2—the most coveted achievement for any naturalist. Beger measured people with calipers and made face masks. To get people to sit for measurements, Beger offered free medical services to the local populations they encountered. Meanwhile, Karl Wienert took topographical and geomagnetic measurements and Ernst Krause shot film footage. But entry into the Forbidden Kingdom remained elusive even after months of diplomatic efforts.

Then one day the expedition encountered a Tibetan dignitary who worked for the Taring Rajah, a Sikkimese noble residing in Tibet. Realizing that this may offer them a way in, they invited him into their camp and buttered him up, plying him with gifts. Schäfer drew on his experience from previous expeditions and dictated a letter to the Taring Rajah where he casually name-dropped meeting the Panchen Lama. Flattered by the attention, the dignitary bestowed the expedition's gift of vegetables (apparently very rare in those regions) on the Taring Rajah, prompting the Rajah to extend an invitation to the Germans to come and visit him and his wife. Taking along Kaiser (as a translator) and Krause (to shoot footage), Schäfer headed to Doptra inside Tibet where the Rajah resided. Pouring on the charm, they exchanged the traditional white scarves and congenially supped together. Schäfer returned to Sikkim and waited.

The efforts to court the Taring Rajah paid off. A letter arrived from the Kashag—the Tibetan parliament—bearing the official seals allowing them a fourteen-day visit as "tourists" over the strenuous objections of Hugh Richardson, the head of the British mission in Lhasa. No weapons would be permitted, nor would the killing of any animals. The expedition had finally gotten in, but their time in Tibet was strictly limited and they would be unable to pursue much of the scientific research that they had set out to accomplish. But Schäfer had no intention of staying only fourteen days—he was a man used to getting what he wanted.

The expedition set off from Gangtok for Tibet over the Christmas/New Year holiday between 1938 and 1939. Although Kaiser was now a beloved member of the team, they acquired a new translator who actually spoke Tibetan whom Schäfer was convinced was secretly reporting to the British. They assembled a yak caravan, mounted swastika banners onto the yaks (a sacred symbol in Tibet ), and made their way through the Natu La pass and across the Chumbi Valley towards Gyantse, braving the harsh Tibetan winter.

At this time, the "Great Thirteenth" Dalai Lama had died, and the fourteenth Dalai Lama (the current one) was imprisoned in the Kumbum monastery in Amdo. In the interim, Tibet was governed by the Reting Rimpoche (the Regent) along with the Kashag, which consisted of four influential members called shapés.

Arriving in Lhasa in January 1939, the Germans wasted no time in currying the favor of Tibetan officials, much to the consternation of the British and Hugh Richardson. Knowing that time was running out, Schäfer decided to launch yet another of his trademark charm offensives. He threw a massive banquet for the shapés, again plying his targets with alcohol and gifts. Before the banquet, he drilled expedition members in the proper protocol hoping to leave a favorable impression.

He was assisted in his efforts by a monk named Khenrab Künsang Möndrong, who was formerly the head of the police. In his youth, "Möndro" had been taken by the British to study in England before returning home and becoming a monk. Frustrated by what he saw as the backwardness of Tibet, and impressed by the Europeans, Möndro became a critical ally3. Another factor in their favor was that Beger had set up an informal medical clinic where he treated Tibetans with a variety of ailments using whatever medical knowledge and equipment he possessed (apparently STD's were rampant—especially gonorrhea—even among the monks).

Schäfer's charm offensive once again paid off but they were granted only eight more days by the Kashag and told that they had to leave before the New Year festivities, as their safety could not be assured once the city was flooded with tens of thousands of monks and pilgrims. Möndro informed them that a longer extension was blocked by a single official whom they had neglected to invite to the party. Schäfer paid the recalcitrant official a personal visit, while Beger treated his sick wife with aspirin. That did the trick, and the expedition's stay was extended a full two months until March 8th, once again to the chagrin of Hugh Richardson and the British.

Political tensions were running high with the German occupation of the Sudetenland, and the German and British missions kept their distance: "Schäfer did his utmost to annoy Richardson with provocative nationalist slogans and Richardson began playing radio news about Nazi aggression very loudly from the veranda at Dekylinka. Tibetan officials began to fear inviting the two parties to the same events." (HC, p. 272) The British routinely intercepted the Germans' mail and electronic communications.

The extension meant that Schäfer and company would be able to record the spectacular Tibetan New Year festivities, which they did, becoming the first Westerners to do so. They also acquired plenty of rare ethnographic materials, including a copy of the Kangyur, one the holiest of all Tibetan texts. They persuaded the Regent to write a personal letter to Adolf Hitler and send along some gifts, both of which Schäfer deemed woefully inadequate. During one meeting, the Regent surreptitiously raised the possibility of acquiring guns from Germany (which eventually got back to the British). During the filming of one of the New Year events, Schäfer and Krause were stoned by monks. Playing up their injuries, they remonstrated to Tibetan officials who, by way of apology, further extended their stay by another couple of months.

Schäfer still hoped to get to Nepal or even Kashmir—a prospect that caused shockwaves of alarm in the Foreign Office. As a result of the stoning, the Kashag had offered the expedition another two months in Tibet. After much discussion, it was decided to remain within Tibetan borders and travel east to Tsetang and the Yarlung Valley and then return west along the Tsang Po to the great city of Shigatse. After that they would hopefully head south back to Gyantse and the Indian border—if the British would allow it. (HC, pp. 279-280)

They set off from Lhasa with Möndro in tow, traveling to Shigatse where they were greeted by enthusiastic crowds. In the Yarlung valley, they went to the oldest building in Tibet which, as an irritated Richardson pointed out, even the British had not been allowed to visit. They traveled as far as Podrang, the oldest inhabited village in Tibet, before turning back towards the Tsang Po River. Along the way, Schäfer shot animals with a slingshot (and secretly a gun whenever he could), while Beger continued to take anthropomorphic measurements. Krause filmed more footage and Wienert set up magnetic stations. In his dispatches to the Foreign Office, Richardson claimed that the Germans were unpopular and offended the locals, but this was not actually the truth—it was merely a desperate attempt to save face.

During this time, Schäfer grew more and more paranoid, alienating the rest of the group. It wasn't without reason: by this time the Germans had occupied Czechoslovakia, and the British now wanted the Germans out of Tibet at any cost. This was exacerbated by the publication of a newspaper article Schäfer had written while still in Sikkim where he disparaged their treatment by British officials—a major diplomatic faux pas. The drums of war were now beating loudly in Europe, and the expedition's family members—including Schäfer's father—pleaded with them to come home lest they be detained at the war's outbreak4. In May the expedition returned to Gyatse where Schäfer negotiated with Basil Gould for their exit from Tibet. Schäfer once again pleaded with Gould and British officials to let him to take Kaiser back to Germany to no avail—the British officials were too suspicious of his motives5.

With the outbreak of war increasingly imminent, the expedition packed up the huge collection of valuables, specimens and filmed media they had acquired and headed to Siliguri where they caught the train to Calcutta. Fearing their detention by the British and not wanting to lose their valuable discoveries, Himmler personally sent a Sunderland flying boat to pick them up from Calcutta. From the Bay of Bengal they flew to Baghdad where they transferred to a Junkers U90 which took them to Vienna. From Vienna, a U52 took them to Munich where Himmler personally greeted them, and from there they flew to Berlin where they arrived on August 4, 1939 to a hero's welcome. Less than a month later, World War Two would commence with the German invasion of Poland.

Christopher Hale sums up the Nazi Tibet expedition:

At the beginning of January 1939, five Europeans with a caravan of servants and muleteers approached Lhasa, the Holy City of Tibet. They had travelled across the Himalayas from Sikkim, a tiny kingdom in northern India, and would spend the next eight months in Tibet. They did research which mystified the Tibetans, and occasionally hunted. They took more than 60,000 photographs and exposed more than 120,000 feet of movie film. At a time when Tibet awaited the arrival of a new Dalai Lama, the five Europeans formed close, sometimes intimate friendships with Tibetan nobles and religious leaders, including the Regent. They clashed frequently with the British Mission officer stationed in Lhasa who had tried to prevent their journey and bitterly resented their presence in the 'Forbidden City.'

In August 1939, the five men fled south to Calcutta, taking with them 120 volumes of the Tibetan 'Bible', the Kangyar, hundreds of precious artifacts and assorted rare animals. At the mouth of the Hoogh River, they boarded a seaplane and began the long journey home—first to Baghdad, then to Berlin. Home for the five Europeans was Nazi Germany. When their aircraft touched down at Templehof Airport an ecstatic Heinrich Himmler was waiting on the runway. For the Reichsführer, the 'German Tibet Expedition' had been a triumph. (HC, pp. 8-9)

The Aftermath

Ernst Schäfer became a minor celebrity upon his return. He was presented with an SS death's-head ring and the ceremonial sword, the Ehrendegen, which was inscribed with a runic double lighting bolt, and became part of Himmler's inner circle. He remarried within six months of his return and started a family, even as he wistfully thought about the youthful charge he had been forced to leave behind.

In 1940, as the war raged, he proposed to Himmler that he and Karl Wienert could parachute into Tibet to become a sort of German version of T.E. Lawrence, rallying the Tibetans to rebel and carry out clandestine attacks on British targets in Tibet and India. However, that proposal died after the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. In 1942—the year of the train attack—he was appointed as the head of the Reich's Central Asian research agency in Munich, which was later renamed in honor of Sven Hedin who declared Schäfer to be his logical heir. At the opening of the Sven Hedin Institute for Central Asian Research, the film of their journey, Geheimnis Tibet (Secret, or Hidden Tibet) finally had its premiere, distilled from thousands of hours of footage. It's still shown in Germany today with the Nazi references tastefully edited out.

Little is known of Geer and Krause, who faded into obscurity. Bruno Beger's post-expedition journey was quite darker. He ended up measuring the skulls and bodies of Central Asian prisoners of war killed at Auschwitz in 1943:

In June 1943 Beger undertook another journey in pursuit of Aryan ancestors who had proved to be rather elusive in Tibet. His destination was the Auschwitz concentration camp. Here he made a selection of more than a hundred Jews and prisoners from central Asia. He measured their skulls and bodies and had face masks made. When Beger left Auschwitz and returned to Berlin, every one of the men and women he had worked on were gassed. The corpses were delivered to SS Dr August Hirt, an old friend of Beger, to become part of a university anatomical collection. By this time, Schäfer was the proud head of his own 'Institute for Central Asian Research', named after Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, headquartered in a castle near Strasbourg. He was pleased when Beger, as instructed, sent him the data and face masks he had acquired in Auschwitz. One individual, Beger was pleased to report, had 'perfect Tibetan features'. (HC, pp. 14-15)

Some of the items brought back from Tibet included thousands of specimens of hardy, cold-resistant grasses, including a fast-growing barley which was a staple food on the Tibetan plateau. As the war turned against the Germans and food ran out, Schäfer's institute was tasked with undertaking research on these grasses to try and develop crops which could feed the increasingly desperate population as the war dragged on. Later efforts also included breeding special horses. None of these efforts, of course, would alter the outcome of the War in any way.

After the War, Schäfer—never the most enthusiastic Nazi—cooperated freely with the victorious Allies, turning on everyone he could in order to gain clemency for himself. He managed to avoid a prison sentence. Later, he worked as a naturalist in South America, penning several more books about his adventures. Beger, despite his connection with the death camps, also received a suspended sentence. Beger, remarkably, was still alive in 2002 for Hale to interview for Himmler's Crusade.

So that's the real story. Himmler's Crusade is extremely well-written and makes for fascinating reading, even if you have no particular interest in the Nazi expedition to Tibet. It’s full of vivid descriptions of a culture and region which, sadly, is no longer the same. Both Tournament of Shadows and Himmler's Crusade provide the relevant context of previous European encounters with Tibet, including the 1904 expedition by British Colonel Francis Younghusband into Tibet by force of arms against the wishes of the natives (which so shocked the British when Schäfer attempted to do the exact same thing). It also details earlier explorers like Americans Joseph Rock and Charles Suydam Cutting, among others.

Reading the book, it's hard not to develop a reluctant liking for Schäfer. He comes across as a charismatic—even sympathetic—figure, yet also at times temperamental, domineering and arrogant. From his photos he looks like a cross between Sir Kenneth Branagh and Kevin Kline6. Schäfer's Nazism was always a product of vanity and overweening ambition rather than ideological commitment, although it's hard to excuse him for that. All in all, he presents a fascinating character study for any aspiring novelist.

The Fake Story

According to occult and cryptohistorians, Hitler sent annual expeditions to Tibet from 1933 until the end of the War. This isn't true—the expedition I described above was the only Nazi mission. They also claimed that colonies of monks lived in Berlin, and that they chanted to produce favorable weather for the invasion of the Soviet Union. This, too, is false. There were no Tibetan colonies in Berlin, nor were they predicting the future or manipulating the weather. Another fanciful story was that the expedition left behind a radio transmitter for Hitler to regularly communicate with the Dalai Lama. This is clearly false, as Tibet was ruled by a Regent at the time and the Dalai Lama was still a child who had not yet been enthroned.

As for the expedition's ultimate purpose, well, the occult and cryptohistorians have their own ideas. They believe that the expedition was really searching for Shambhala and/or Agarthi and sought to procure an alliance with the "Hidden Masters" to take over the world. Christopher Hale runs down some of these theories:

What were SS scientists sponsored by Heinrich Himmler doing in Tibet as Europe edged toward the precipice of war? Many different explanations have been offered and scores of conflicting stories told. Here are some of them: ‘The German expedition to Tibet had as its mission the discovery of a connection between lost Atlantis and the first civilization of Central Asia’; ‘Schäfer believed that Tibet was the cradle of mankind, the refuge of an “Aryan root race”, where a caste of priests had created a mysterious empire of knowledge, called Shambhala, adorned with the Buddhist wheel of life, the swastika’; ‘This small troop delivered to the Dalai Lama a radio transceiver to establish contacts between Lhasa and Berlin’; ‘The SS men were magicians, who had forged alliances with the mystic Tibetan cities of Agarthi and Shambhala and had mastered the forces of the living universe’; ‘They had mined a secret substance to prolong life and to be used as a superconductor for higher states of consciousness’; ‘In the ruins of Berlin, a thousand bodies with no identity papers were discovered by the Red Army. They were all Tibetans.’ Every one of these statements is false; some are transparently foolish. (HC, pp. 9-10)

But if you’re writing fiction, well, take your pick.

While the above theories are certainly false, what is true is that many influential people in the German high command—including Himmler himself—had some strange ideas about Tibet which may have factored into expedition’s ultimate aims. As Meyer and Brysac write in Tournament of Shadows: “Other considerations had entered into Himmler’s fascination with Tibet. It had long been reported that fabulous gold riches might be found in the Himalayan kingdom, and Schäfer took this up in talks with Tibetan authorities, who seemed interested in ties with a potentially helpful European state.” (TOS, p. 520) Christopher Hale relates this rather colorful story of an encounter between Bruno Beger and Karl Maria Willigut just before the mission departed:

In Berlin, Beger had had one last encounter with the sinister world of their patron, the Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. He was working late at the Ahnenerbe offices in Dahlem and in the early hours of the morning went in search of a suitable place for a nap. He found an unlocked and empty office equipped with a large and inviting sofa. The building was quiet; Beger stretched out and rapidly fell asleep. He awoke suddenly to find and old man sitting at the end of the sofa regarding him intently. It was Karl Maria Wiligut, or ‘Weisthor’, Himmler’s Rasputin. Wiligut was by now disgraced and probably mentally ill; his obsession with runic law and his millennia-old ancestral race memories were indulged only by Himmler.

Beger apologized and began to leave the office, but Weisthor knew who his intruder was and had some requests. Beger must find out as much as he could about marriage customs in Tibet. Women were said to take a number of husbands. Would this practice, if adopted by the SS, permit the biological manufacture of yet more pure-blooded Aryan SS men? Weisthor had also heard an intriguing legend: Tibetan women were though to carry magical stones lodged inside their vaginas. Would the expedition please find out if this was true? Then this peculiar old man said goodnight and shuffled painfully away though the dark Ahnenerbe offices. (HC, p. 155)

So that's the Nazi portion of our story. But where do the Americans come in? And who is our Indiana Jones?

To get to that story, though, we first have to learn about a now little-known Russian painter and mystic who managed to change the outcome of two U.S. presidential elections. Hang on, because things are about to become even stranger...

Next: Galahad and the Guru

The ä in German is a long 'a', as in cake or make. Also sometimes spelled 'Schaefer' or 'Schaeffer' in English.

Hermitragus jemlahicus schäferi; although it’s been disputed whether the animal is much different from the tahr, another goatlike mammal (HC, p. 186)

Möndro was apparently bisexual and became obsessed with sleeping with Beger. An amusing anecdote in Himmler's Crusade relates an incident where Möndro tries to take Beger home with him. Realizing they need to string him along, Beger initially plays along but manages to back out of a potential intimate encounter at the last minute.

As was Heinrich Harrer, the Austrian mountaineer who later escaped his internment and wrote Seven Years in Tibet (and who, like Schäfer, was an SS officer).

While the British were suspicious of his motives, Schäfer's intentions toward the boy were apparently pure and motivated more by genuine loneliness than anything else. He intended to make Kaiser a member of his family even if he remarried, which he did. British officials also feared that Kaiser would convert to Nazism and be sent back to Nepal to work as an undercover agent for the Germans. Hale considers some evidence for this.

Sir Kenneth, from Northern Ireland, has played Nazis Henning von Tresckow in Valkyrie, Reinhard Heydrich in Conspiracy, and SS-Sturmbannführer Knopp in Swing Kids.

Yo yo working class n⭐️⭐️ga is here!

Really enjoying these (especially since I’m unlikely to read the books). Almost sprayed a mouthful of my morning coffee over my phone upon reading this one:

“Ten months before the expedition set sail, Schäfer—despite being an expert marksman—had shot his new bride in a hunting accident, killing her.”