So, where did inequality come from?

After 525 pages of The Dawn of Everything plus endnotes, we still don't have a very good explanation. We do have some inkling about how it occurs: through control of violence, control of knowledge, and exceptional charisma. We also know that some of the more simplistic explanations don't hold up. Clearly it was not just an inevitable consequence of surpluses, or population growth, or sedentism, or farming, or occupational specialization, or technological development. The Davids' own explanation—that it was the abandonment of flexible social relations due to the atrophying of political consciousness—doesn't seem very convincing, either.

In an excellent article for Aeon Magazine a while back, the author posed the question, "How Did Equality Slip Away?" He points out that, in the societies we live in today, there is no mystery as to why inequality exists. Modern societies have strictly defined roles and institutions backed by the legal application of force. The real question, then, is not why our current societies are so unequal, but how this initially came about when we spent the vast majority of our existence as a species in small groups with flat hierarchies.

Somehow, after 290,000 years of living without anyone having the power to tell us what to do, and with every member of a community having about as much as everyone else, most of us are now subject to command, and with immensely less than a favoured few. Why?

Of course, in the state societies we live in, there’s no mystery about the many accepting their subordination to elites. While elites are vastly outnumbered, they control the army, the police, the state apparatus. An attempt to seize elite wealth would be met by overwhelming coercive power, and even successful revolutions have a dismal record of largely replacing one elite with another...

Once hereditary leadership backed by military power establishes, subordination and inequality are explained by entrenched differences in access to force. So the critical problem is to explain inequality in village societies where it doesn’t yet have the protection of institutionalised power.

How equality slipped away (Aeon)

Lately I've been reading a book with the cumbersome title, The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Empires by Ronald M. Glassman, which addresses these questions. I forget where I first heard of it—I think maybe it turned up in some searches on Google Books. The book itself is pretty obscure. I haven't heard much discussion of it anywhere, and even Google searches turn up very little. I doubt very many people have heard of it (it’s not listed in The Dawn of Everything’s bibliography).

There may be some reasons for that. One is the book's staggering length—it checks in at a whopping 1700 pages! Another may be the cost—hard copies can't be found anywhere online for less than almost two hundred bucks. I'm not sure the reason for this, except it might be a textbook. Glassman himself seems pretty obscure. From what I can find, he teaches sociology at various colleges in New York. He is certainly not a widely known intellectual figure like David Graeber or David Wengrow, or the Big History authors they argue against like Jared Diamond, Yuval Noah Harari, Ian Morris, Francis Fukuyama, and Steven Pinker.

Fortunately, I was able to find a free electronic copy back when that sort of thing was possible. This is a good thing, as the book has some very convincing explanations for how societies become more unequal over time that are compatible with Graeber and Wengrow’s criticisms of Big History narratives.

I think that Glassman's ideas gel remarkably well with Graeber and Wengrow's work; so much so that I think their ideas are complimentary, rather than oppositional. In addition, I think it provides a good bridge between The Dawn of Everything and the ideas of other social theorists like Peter Turchin (in Ultrasociety); Kent Flannery and Joyce Marcus (in The Creation of Inequality); and the Aeon article listed above. In fact it does this so well that I'm amazed this book isn't more widely known. Glassman, as he notes in in his introduction, combines several sociological approaches, especially those of Karl Marx and Max Weber, along with Aristotle, Hobbes, and Machiavelli, among others, as well as abundant anthropological and historical examples.

The Origin of Democracy

Like Graeber and Wengrow, Glassman argues that deliberative democracy is the most natural form of human political organization, and that it is despotism which demands an explanation, not democracy. The reason is because humans have the unique ability to communicate using abstract language, which allows us to collectively deliberate in groups and debate alternative courses of action and different points of view.

This sets us apart from other animals, including our closet living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos. In other primate social structures, there is no rational deliberation—leadership is based on physical strength and intimidation. Of course, in chimpanzee groups, leaders must also exhibit a level of social adroitness because unbridled despotism invites coalitions of rival males to unite and depose any would-be tyrant. Among bonobos, females act as the glue which holds the social structure together (which is replicated in humans to some extent, as we'll see). Nevertheless, there is no rational delegation of leadership roles, nor is there rational deliberation among the members of primate groups.

Humans are different. We are capable of rational thought, discussion and deliberation. And our use of weapons ensures that, unlike chimpanzees, domination by the physically strongest members of the group is not possible.

Based on what we know, humans have spent most of our evolutionary history in small, nomadic foraging bands. There is some dispute over how long this has been the dominant social form, but there is no doubt that it is an institution which has very deep roots. In these societies, "campfire democracy" prevails. Leadership is by consensus and there are no institutionalized leadership roles. Differences in wealth are minimal to nonexistent. Because we are a species dependent on social learning and cultural transmission to survive, older individuals were accorded a higher degree of status and authority in band societies and men typically dominated political discussions, perhaps because men formed the core nucleus of the band while women were exogamous, or because of their proficiency with weapons. Although there were still inherent differences between individuals in a band, none of those led to some people being able to impose their will on others or dominate political decision-making.

Thus, it is obvious that humans always have been endowed with a "political consciousness" as the Davids argue so forcefully throughout The Dawn of Everything.

So if democracy is our "default" form of political organization, why is despotism so common? That is what Glassman's book is intended to explain.

The Origin of Despotism

Glassman sees the roots of despotism in the transition from hunting societies to tribal societies which focused more intensively on plant foods engendered by the warming climate of the Holocene and the extinction of large game animals. The tribal form of social organization allowed human societies to grow much larger than band societies, but it also led to major social changes, including greater complexity and material sophistication.

A band society is one where its members reside in mobile foraging bands spread out over a wide territory for most of the year. A tribal society, as the term is generally understood, is one where people are organized into descent groups usually referred to as clans or lineages. The clan is the primary social grouping in a tribal society rather than the band, which is less formal and not based strictly on kinship. Clan societies have cross-cutting institutions which integrate the various clans. The most common are age grades and intermarriage, along with pan-tribal sodalities and other corporate groups. Sometimes there are also higher levels of multi-clan groupings such as phratries or moieties.

Unlike herd animals, plants don't move which led to greater sedentism. It's likely that gardening activities originally alternated with seasonal hunting expeditions and communal hunts in the sort of dual-mode existence that the Davids portray so vividly. But it also meant that groups were more vulnerable to attack and were less able to move away in the event of conflict with other groups. This led to increasing armed conflicts between foragers, although in the early days such conflicts were still relatively minor with few fatalities.

The transition, then, from nomadism to sedentism, and from hunting to planting, led to the tribal mode becoming the predominant form of social organization after the end of the last Ice Age.

Because gardening is an outgrowth of the gathering activities of women, women ended up producing a much greater share of the food compared to the hunting activities of men. This led to an elevation in their status. According to Glassman, this is why the original form of clan organization was reckoning descent through the mother's bloodline, which he calls matri-clans. This also makes sense because maternity is known with absolute certainty, whereas paternity is not.

Because women alone were able to bring new life into the world, this led to them being endowed with a mystical reverence. Women gave life to plants by growing them in the soil and gave life to humans through their bodies. They were life-givers:

For was it not true that only women could produce new humans? And was it not true that only women could nurture these infants and make them live and grow? And so women in horticultural society were invested with the mystique of fertility. They were seen as the life givers and the life sustainers, nurturers of man, cultivators of the earth. The earth itself was likened to a woman, and thus mother earth gave birth to its offspring while the women, as midwives, delivered and nurtured the earthly productions.

And so women gained the highest status in horticultural society—Earth goddesses were worshipped as the highest gods, fertility figures were fashioned after her, creativity was seen as hers and hers alone, and priestess rivaled priest for high ritual honor and ritual control. (180)

Meanwhile, men provided relatively fewer of the group's calories as humans' favored prey animals disappeared and we spent less time wandering. Sure, occasional hunting expeditions still provided valuable meat, fat, fur and hides, but it was much less prestigious than before. With animal domestication, hunting became even less important. Faced with the diminution of their status, and with more free time on their hands, the men increasingly focused their efforts on religion and politics.

Sedentism and cultivation allowed for a steady increase in population. Because the women were not on the move, it was easier for them to look after children and space births closer together. The reliable supply of food, especially foods that could be stored, sped up population growth. This meant that tribal societies got bigger. Storable foods undermined the sharing ethos present in hunting societies.

Rather than fissioning as bands tend to do, the tribal form of social organization allowed these larger societies to remain intact, even if camps and settlements were spread out across long distances. But it also meant that tribes rubbed up against each other more often than before, causing tension. Sometimes even neighboring villages of the same tribe found themselves in conflict, resulting in tit-for-tat feuds. New political institutions were required for pacification, like intertribal games and village headmen who could negotiate peace.

According to Glassman, early tribal societies were managed democratically by clan councils which deliberated in much the same manner as the hunting council in earlier band societies. However, the basic inequalities of band societies remained in tribal societies—men over women, and old over young. Each clan was represented at the tribal council by clan elders, who were democratically chosen by the members of their clan. Elders were always men, although women still wielded a great degree of influence by being clan matrons and producing most of the food. The clan council deliberated on all important matters, with unanimity required for final decisions.

The clan form of organization called forth new social roles. Glassman makes much of two of these in particular: the warrior chief and the shaman.

The warrior chief was elected to lead the warrior fraternities in battle. However, the warriors themselves were still embedded in their clans, preventing them from forming a separate power center to monopolize violence or pass down wealth to their offspring, since all wealth was collectively owned and distributed by matri-clans. Meanwhile, the shaman was an eccentric individual who was designated by the tribe to communicate with the spirit realm via trances and do things like heal the sick or make the rains come.

While each of these roles permitted its holder to accumulate a degree of power compared to the rest of the tribe, their power was held in check by the clan assembly and clan matrons who could remove them from office, or even kill them if they attempted to abuse their authority or hoard resources. The norms of egalitarianism still prevailed, and booty captured in raids was given away in elaborate ceremonies. Appointment to these offices was usually based on competence and charisma, and was not hereditary.

In small-scale tribal societies, these institutions all balanced out among each other. The warrior-chief, the shaman, the clan elders, and the clan mothers were all independent power centers that acted as checks and balances on each other. No single group or individual, no matter how charismatic, could dominate for very long. This led to a fairly egalitarian social arrangement where no one faction was able to monopolize wealth, violence, or decision-making. Power came through persuasion, not force. Glassman uses the example of the Iroquois horticultural societies to illustrate this dynamic. It's no surprise that this was the culture that Kanidaronk came from:

Charisma and manufactured charisma were minimized in these small-group societies. Cooptation was difficult where few gifts of wealth, power, or family could be conferred by leaders. Terrorization and naked force by leaders and cliques against the band or tribe at large were effectively inhibited by the checks and balances of other leaders and cliques and institutions within band and tribal society.

The possibility of usurpations of power or wealth were so limited in band and tribal society that little ideological manipulation to justify leadership activities was necessary, skilled performance and personal charisma being enough to justify leadership to the people, and status being enough to satisfy leadership demands. The intimate, stable, slow-changing, economically poor, and politically isolated nature of tribal society, and the cooperative economic and political necessities of primeval life all militated toward rational legitimacy processes. (147-148)

From tribal societies, then, human cultures forked along two basic paths based largely on ecology. Some societies ended up becoming horticultural societies, settling down permanently in villages alongside their garden plots to raise various crops. The other path was to become a herding (or pastoral) society based around the keeping of livestock. These changes, in turn, disrupted the old tribal balance of power and opened the door to despotism.

According to Glassman, as they expanded, horticultural societies became gerontocratic theocracies. Tribal elders formed their own power center and manipulated the puberty ritual in order to terrorize the young. They developed age grades to create a "ladder" of authority based on age, excluding the younger generations from power. Since everyone will eventually become old, this was not seen as tyrannical by the rest of the tribe even though it was. They created institutions like men's lodges where membership could be restricted and knowledge—especially ritual and sacred practices—could be enshrouded in secrecy. This led to the first primordial form of power asymmetry: gerontocracy.

Shamans formed cross-village fraternities, developing into an incipient priesthood which established hierarchical grades presided over by the high priest. The priesthood monopolized the tribe's religious and ceremonial authority and manipulated the supernatural belief system in order to accumulate status and power for themselves, enhanced by their knowledge of herbal medicines and poisons1. This was the second primordial form of power asymmetry: theocracy.

The village elders and shamans forged an alliance to use their esoteric knowledge to monopolize political power. Priest-elders donned masks to represent the spirits and terrorize the rest of the community, engaging in random acts of violence and even human sacrifice. The rational authority of the tribal council was overcome by irrational authority based on supernatural beliefs in capricious gods and spirits culminating in what Glassman refers to as the cult state:

We have already suggested that the institutions upon which the rational legitimacy processes were grounded—the clans and the tribal council (and confederated tribal council)—became ineffective in maintaining order. Clan justice degenerated into murderous feuding, while the tribal structure proved unreliable in a setting of contiguous cross-tribal village clusters (or expansionary herding units) pressing against one another almost continuously.

Among horticulturists, the mechanism for maintaining order—the theocratic cult-state—did produce a new order through the use of religious terror and manufactured charisma (surrounding the priestly officials). Once the use of this form of ideological manipulation arises—that is, the ideology of demon-spirits demanding ritual and taboo activity—it becomes almost impossible for the population to engage in rational, open debate on political matters. (271)

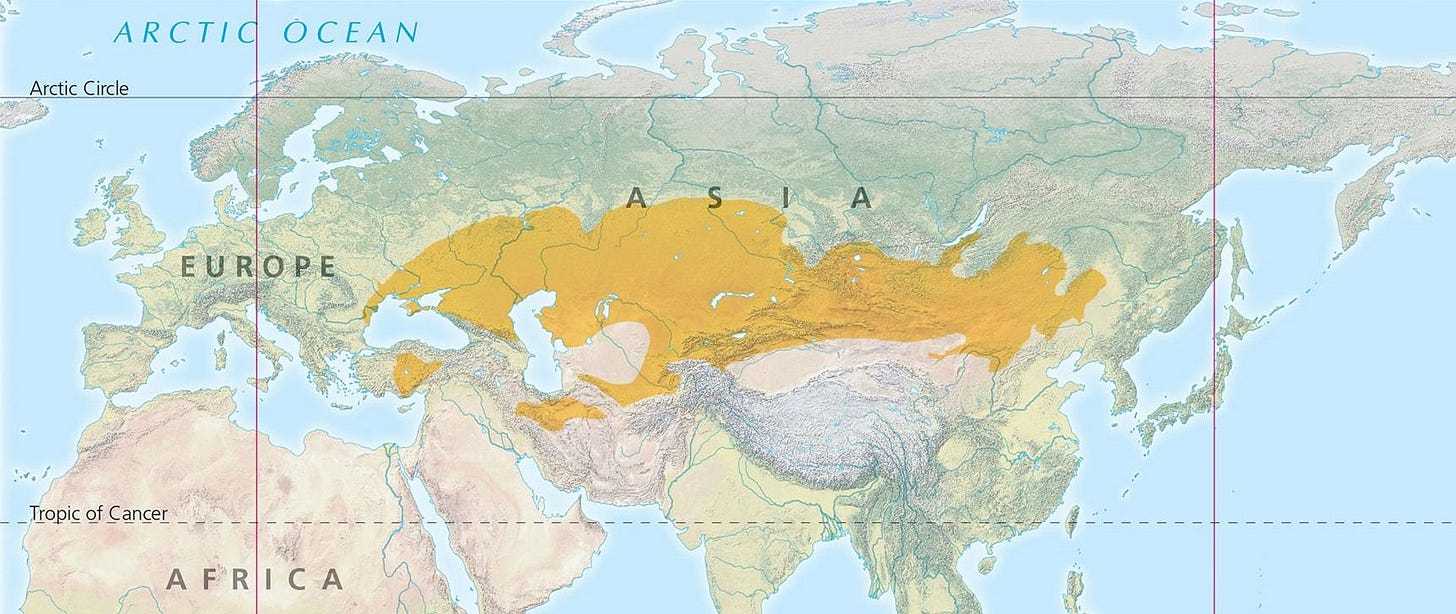

Pastoral herding societies went a different direction. They transformed into societies based around male coalitional violence which perfected the art of total war, with the aim of wiping out rival tribes completely. This led to the warrior chief being elevated to an all-powerful figure who was able to overrule the authority of the tribal council. Age grades were co-opted by the war chief to form an incipient warrior caste who gained exclusive control over the use of violence—the third major form of power asymmetry. Tribal warriors became loyal to their chief rather than to their clans and reaped property, slaves and women though raiding. This was the beginning of private property—property not under the control of the collective.

Booty seized by warriors in battle (including chattel, livestock and women) was passed down outside the clan structure, leading to matri-clans being supplanted by patri-clans where wealth and status was passed down from father to son. Lavish displays of wealth replaced open-handed generosity and redistribution, and individual glory was celebrated rather than mocked. Women's status degraded to virtual chattel, and successful chieftains were able to amass large harems.

Eventually the war-leader became the chief, the warrior fraternity became his retinue, and his residence became the royal court. Glassman cites the Zulu kingdom under Shaka as a historical example of this process unfolding, and sees many similarities between Shaka and the life of King David described in the Old Testament (also originally a nomadic herding people).

War chiefs were already important figures in the hunting-horticultural tribes. But there, their power was restricted by the clan elders of the matrilineal clans of the tribe. Since warfare was more genocidal and piratical among herding tribes, the role of war chief became more and more important, eventually developing power beyond the restraints of the clan elders.

Here we wish to emphasize that all over the world, herding tribes expanded and became ever more warlike and genocidal in their assaults. Therefore, during and after the period of civilization in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, and elsewhere, herding tribe conquests of these civilizations impressed both the military kingship and the patrilineal clans on these civilizations.

Thus, in most areas of the world, the status of women declined, and; the status of conquered men declined as well as slavery became institutionalized on a large scale. Once this occurred, tribal democracy began to disappear completely in many areas of the world. (218-219)

It was the interaction, then, of materially and socially-complex horticultural societies with less sophisticated hierarchical warrior societies which eventually led to what we call civilization. This, Glassman says, is the origin of inequality and despotism.

Glassman's theory is consistent with Graeber and Wengrow's contention that early planting communities were mostly egalitarian with women having high degree of status and autonomy. It's also consistent with the idea that women played a central role in the spirituality and social organization or tribes via their roles as earth priestesses and clan mothers. This is consistent with the archaeological evidence we have of early neolithic farming communities all over the world—from Çatalhöyük, to Minoan Crete, to the Balkans, to Iberia, to West Africa and the Pacific.

Meanwhile, pastoral-herding societies developed along the lines of the "heroic" societies that Graeber and Wengrow profile in chapters 8 and 10, being far more hierarchical, patriarchal, and militaristic than horticultural societies despite being numerically smaller, materially simpler, and less intellectually advanced (no writing, mathematics, architecture, etc). This is also consistent with the archaeological evidence from places like the Eurasian steppe, the highlands of the Near East, and the Sahel.

This is also consistent with Graeber and Wengrow's three elementary forms of domination. In horticultural societies, control of information was used to dominate others. In herding societies, control of violence was used to dominate others. And in both societies, charismatic authority was manifested in the roles of the warrior chief and shaman. As they note, these three elementary forms of domination would come together in various permutations to form what we call "states."

Because the primordial form of society was democracy, this explains the remnants of democracy we see all over the world even under despotism, many of which are described in The Dawn of Everything—for example, the citizen assemblies in early Mesopotamian cities which no doubt descended from the old tribal village councils, or the Balinese subak. It also explains why we so often fall back to democracy when despots fail to hold on to power—for example, the Davids' depiction of Teotihuacan in chapter nine.

In keeping with Glassman's thesis, then, democracy is not unique or unusual, nor does it have to be "discovered"—rather, it is the default mode of human political organization, and the one we fall into in the absence of despotism, rather than despotism being a deliberate and rational choice to help large groups cooperate once they reach a certain size threshold. This is also consistent with the Davids’ criticism of seeing top-down command and control structures as the default mode of human social arrangement in the absence of contravening evidence; while democratic, bottom-up decision making is assumed to be an aberration which requires explanation and incontrovertible proof of its existence.

Glassman summarizes his thesis:

When bands expanded due to the adoption of horticulture or to better hunting techniques or improved weaponry, they often remained in alliance with one another. Thus, kinship-related, allied bands formed into larger units, supported by an increased food supply. These larger units of allied bands came to be called “tribes”—first by Middle Eastern and Greek intellectuals and then by modern anthropologists.

Tribes, as opposed to bands, are characterized by a superior mode of production and a superior warrior organization, along with the development of a crucial new social unit, the clan—or extended family. The superior mode of production includes rudimentary horticulture, or small-scale gardening by the women, and more successful hunting techniques by the men. These engender a marked increase in population. And this latter engenders expansion and encroachment on other tribes’ warfare organization for the tribes’ survival.

When tribal groupings appear, the ability for human groups to simply fission off from one another disappears. Hence, conflict between human groups intensifies...All of these factors led to the emergence of human groups that were larger in population size and more complex institutionally. Pairing families became large clans; campfire councils became tribal councils, with clan representatives; warrior organizations emerged with charismatic war leaders and structured regimentation; and individual shaman gave way to more organized priesthoods with more political power.

All of these factors led to new and more complex political institutions. And some of these institutional trends led to a more formalized democratic process, while other trends led to the emergence of new forms of despotism. For, as we have established, humans...are at once animals, sharing the drives and needs of animals...As animals, we respond to domination with fear and obeisance, we defend a territory against predators and other humans, we fight with each other, and we have sex with each other. As human beings, we intelligently discuss problems and make rational decisions, we respond to mysticism and to charismatic leaders, and we regulate group conflict and sexual unions with norms and laws.

Both of these aspects of human beings exhibit themselves in the political institutions of human groups. From the very beginning of our primeval emergence from our primate past, this dual nature of humans has played itself out in the political processes of human groups, with rational-democratic institutions competing with irrational-despotic institutions. Democracy and despotism are both part of the human potential... (from the Introduction)

The book is divided into multiple parts. Part 1 describes the dynamics I've outlined above, where primordial democracy was supplanted with various manifestations of despotism, hierarchy, and institutionalized power. It is divided into an introduction and four sections devoted to each of the major social transitions: band societies; tribal societies; horticultural village societies (matri-clans); and nomadic pastoral herding societies (patri-clans).

The remaining parts of the book are devoted to various historical examples. Part 2 looks at the transition from tribal societies to city-states in ancient Mesopotamia and the transition of Israelite society from nomadic herders to kingdoms. Part 3 looks at the Ancient Greeks and their transition from tribes to city-states. Part 4 looks at the Nordic peoples and their transition from tribal confederacies to kingdoms, city-states and merchant empires (and eventually, industrialized nation-states).

The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Empires provides a reasonable explanation of how despotism and inequality first became established in the kinds of prehistoric societies described by Graeber and Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything. It also fills in a lot of the flaws, historical gaps, and anomalies they point out in the standard Big History narrative.

At one point in The Dawn of Everything, Graeber argues that even egalitarian hunter-gather societies lived under a kind of despotism, except it was the despotism of invisible gods and spirits, citing his own book On Kings with Marshall Sahlins. This also relates to Flannery and Marcus's ideas in The Creation of Inequality. From a review and summary of their book:

Flannery and Marcus observe that even outwardly egalitarian hunter-gatherers preserve hierarchy by making their supernatural beings the alphas, their ancestors the betas, and themselves the undifferentiated gammas. Moving toward institutionalized social inequality has thus often involved certain gammas’ claiming power legitimated by special—and often hereditary—relationships to these sacred alphas and betas.

If this is true, then despotism was simply a reification of preexisting conditions. Most early tyrants claimed to be acting according to the will of the gods by creating a sort of divine order on earth: "As above, so below."

Thank you!

Great article!